Relay-runners are now carrying the Olympic torch to Paris. With the 2024 Olympics fast approaching, debate is again heating up about what countries spend on national Olympic teams. Our own country – Australia – has spent a mindboggling 1.2 billion dollars on getting our elite sportspeople to Paris. This is a few times more than what our national government spends on non-elite sport in schools and local communities. This means that each gold medal that an Australian wins at the Paris Olympics will have a price tag of several tens of millions of dollars.

Olympics-bound sportspeople and their managers are convinced that this is money well spent. Indeed, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) continues to lobby for greater public funding. For those going to Paris, the value of Olympic victory is enormous and blindingly obvious. However, for others, 1.2 billion dollars can appear to be wasteful. It is scarce public funding that could be better spent on our doctors, nurses and physical-education teachers.

In Australia, funding the Olympic team is hotly debated among our politicians as well as around our kitchen tables and our office watercoolers. This debate is also now international because other countries – such as Germany and China – are now heavily subsidising their Olympic teams. This is the main reason why Australian Olympians must fight so hard for gold medals.

What is missing in this important debate is a cost-benefit analysis. For example, the AOC rarely details what the benefit of Olympic success might be. A promising way to advance this longstanding debate lies in the lessons of history. Understanding the value of Olympic victory in the past can help us to work out what it might be today.

Of course, it was the Frenchman, Pierre de Coubertin, who, in 1894, founded the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in Paris. Two years later, in 1896, the first modern Olympics took place in Athens. In the 130 years since, the Olympic and Paralympic Games have become the world’s largest secular event. Impressive as the modern Games are, they are still only a small part of a much longer and much older Olympic history.

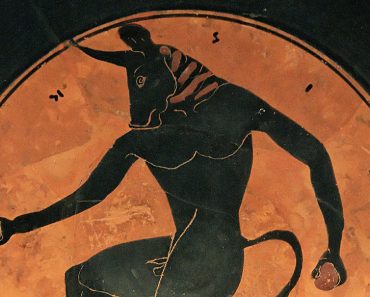

The ancient Greeks staged Olympic Games for 1000 years. Their Olympics attracted sportsmen from right across the Greek world’s 1000 city-states. The ancient Greeks also held clear views about what the value of Olympic victory was. By studying this ancient Olympic history, we can gain new insights in what we get out of modern Olympic success.

The ancient Greeks would have been completely horrified at our heavy state subsidisation of Olympic teams. They did not waste scarce public funding on getting sportsmen to the Games. Individuals were ready for the Olympics because their families had privately paid for a physical-education teacher. Olympians paid for their tickets to the Olympics and their own expenses during the Games.

Nevertheless, the ancient Greeks valued Olympic victory even more highly than we do. Each Greek city-state gave its Olympic victors free meals and free front-row tickets at local sports events – for life. These were the highest civic honours that the Greeks could give. They were otherwise given only to victorious generals. That they were given to Olympians shows that the ancient Greeks believed that such victors significantly benefitted their states.

National Olympic Committees – such as the AOC – might not always be good at detailing the benefit of Olympic success. But the ancient Greeks certainly were. In a legal speech, for example, about the Olympics of 416 BC, a son explains why his father had entered an unprecedented seven teams into the chariot-racing contest there. He did so because he realised that ‘the city-states of victors became famous’. The speaker explained that Olympians were understood to be representatives of their hometowns. Consequently, their victories were ‘in the name of their city-state in front of the entire Greek world’.

What made an Olympic victory so valuable for an ancient Greek state was the international publicity. With 45,000 spectators at the ancient Games, theirs were also probably the world’s largest event. This meant that whatever took place at the Games became known to the entire Greek world as ambassadors, sportsmen and spectators returned home and reported what they had seen.

Greek states fully exploited this opportunity to gain international publicity. We can see this in the incredible discoveries that modern archaeologists have made in the religious sanctuary where the Games were held for 1000 years. This sanctuary was closed in AD 435 when Theodosius II – the Christian Roman emperor – banned all remaining non-Christian worship. Olympia was soon abandoned and slowly covered by metres of silt from a nearby river. In 1874, Germany signed a contract with Greece to excavate this lost site. This contract ensured for the first time that artefacts found in foreign excavations would remain in Greece. Never again would there be a terrible desecration like the one that the Englishman, Lord Elgin, had done to the Parthenon.

German archaeologists uncovered the heart of this sanctuary of Zeus Olympios in only 8 years. Among their discoveries were hundreds of bases of the statues in honour of victorious Olympians. The inscriptions on these bases almost always advertised the name of the victor’s state. Some even stated that his hometown had set up the statue. But German archaeologists also discovered that the ancient Greeks had also set up at Olympia many memorials of their military victories over each other.

In the first eight years of their dig, they decided not to excavate the Olympic stadium itself. This had to wait for a later dark milestone in Olympia’s rediscovery: the 1936 Berlin Olympics. It is still shocking that the Nazi regime used ancient Greek sport for international publicity. As part of this propaganda, it came up with a ritual that we take for granted today: the Olympic torch relay. This is almost completely an invention of the Nazis because there was no such relay at the ancient Olympics.

The German dictator used his own discretionary funds to pay for the stadium’s excavation. Adolf Hitler was not disappointed with what his archaeologists discovered: thousands of weapons and pieces of armour. In ancient Greece, a trophy for a military victory consisted of such items hammered to a pole. The ancient Greeks always set up such a trophy on the battlefield. What Hitler’s archaeologists discovered was that the ancient Greek states had set up duplicate military trophies in the Olympic stadium itself.

Of course, the IOC encourages us to see the modern Olympics as a means of promoting world peace. But these discoveries at Olympia demonstrate that this modern ideal did not apply to the ancient Games. The ancient Greeks clearly used them rather as a means to advertise their success in sport and war.

Because so many Greeks attended the ancient Games, it was possible for the entire Greek world to learn of the sporting victory that a Greek state had gained through one of its Olympians. Such a sporting victory gave city-states of otherwise no importance rare international prominence. For those that were regional powers, it got uncontested proof of the standing that they claimed in relation to their rivals.

The only other way that a Greek state had to raise its international ranking was to defeat a rival state in battle. But the outcome of a battle was always uncertain and could cost the lives of many thousands of citizens. Therefore, an ancient Greek state judged a citizen who had been victorious at the Olympics worthy of the highest civic honours because he had raised its standing and done so without the need for his fellow citizens to risk their lives in war.

This understanding of the benefit of ancient Olympic success helps us to work out what it might be in our own world. It advances the important modern debate about whether the heavy state subsidisation of our national Olympic team is justified.

Today, we still view Olympians as our national representatives, and we are still part of an international system of competing states. Consequently, an important lesson from the ancient Olympics is that international sporting success can improve a state’s international standing. Therefore, the ancient Games do provide some justification for spending serious money on our Olympic team.

Nevertheless, we must not push these parallels too far. For good or for ill, we are no longer ancient Greeks, and sport and war are no longer the only international stages. New bodies – such as the G20, the OECD and the World Health Organisation – also rank modern states in terms of health, education and participation in non-elite sports. In this new world order, we will hold our international ranking only if we spend just as heavily on our doctors, nurses and physical-education teachers.

David M. Pritchard is an ancient historian at the University of Queensland and the author of Sport, Democracy and War in Classical Athens (Cambridge University Press). These are excerpts of the Alex Kondos Memorial Lecture that he will shortly be delivering in Brisbane.