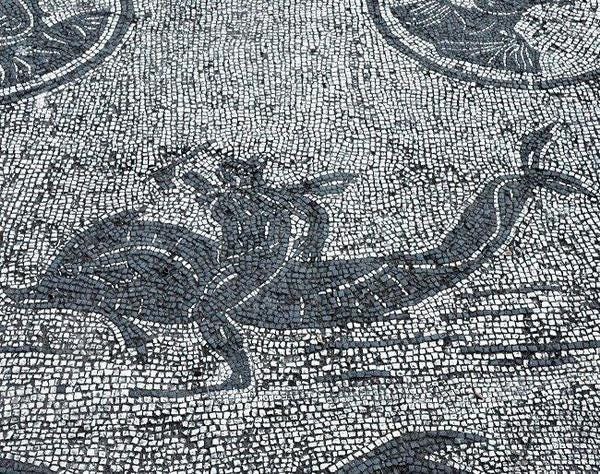

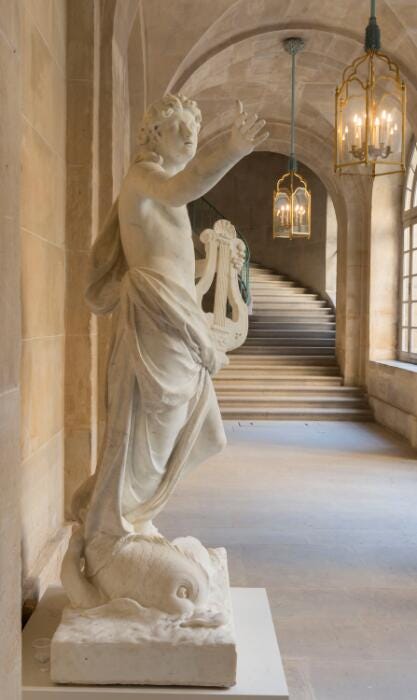

Some ancient poets are historical, some are legendary, and some are a bit of both. Arion belongs to the latter category. He is not quite Orpheus or Amphion, moving trees and rocks with music, though what he does achieve is only mildly less implausible. At the same time, he is generally credited as the inventor of a genre of choral performance, the dithyramb. His story is first told by Herodotus, no guarantee of historicity. Herodotus relates that, while sailing from Tarentum to Corinth, Arion’s ship was boarded by pirates; being forced (more or less) to walk the plank, Arion sought and received permission to sing a song first. After performing, in full singing regalia, the “orthian nome,” a high-pitched song in honor of Apollo, Arion jumped into the sea, and was carried ashore, at Taenarus in the Peloponnesus, by a dolphin; at the place where he was deposited, there was erected a bronze statue of the poet, bearing (according to Aelian) the following inscription:

To save Arion, Cycleus’s son,

at sea the gods sent him this stallion. [my trans.]

Aelian is a notoriously unreliable writer but we can trust him here, since Pausanias the geographer also saw this statue in the second century AD and mentioned it in his Description of Greece: “Among other offerings on Taenarum is a bronze statue of Arion the cithara-player on a dolphin.”

In the following poem, quoted by Aelian (On the Characteristics of Animals, 12.45) to show that dolphins are indeed lovers of music (φιλὀμουσοι, l. 8), Arion appears as speaker (rather than author) in the genre he is credited with inventing:

ὕψιστε θεῶν

πόντιε χρυσοτρίαινε Πόσειδον

γαιάοχ᾽ ἐνηκύμον᾽ ἀν᾽ ἅλμαν⋅

βραγχίοις δὲ περί σε πλωτοὶ

θῆρες χορεύουσι κύκλῳ

κούφοισι ποδῶν ῥίμμασιν

ἐλάφρ᾽ ἀναπαλλόμενοι, σιμοὶ

φριξαύχενες ὠκύδρομοι σκὐλακες, φιλὀμουσοι

δελφῖνες, ἔναλα θρέμματα

κουρᾶν Νηρείδων θεᾶν,

οὓς ἐγείνατ᾽ Ἀμφιτρίτα⋅

οἵ μ᾽ εἰς Πέλοπος γᾶν

ἐπὶ Ταιναρίαν ἀκτὰν ἐπορεύσατε

πλαζόμενον Σικελῷ ἐνὶ πόντῳ,

κυρτοῖσι νώτοις φορεῦντες,

ἄλοκα Νηρείας φλακὸς

τέμνοντες, ἀστιβῆ πόρον,

φῶτες δόλιοί μ᾽ ὡς ἀφ᾽ ἁλιπλόου γλαφυρᾶς νεὼς

εἰς οἶδμ᾽ ἁλιπόρφυρον λίμνας ἔριψαν.

Sublimest of deities,

Poseidon, Lord of the Sea’s

populous womb, whose trident is all gold,

who have the whole planet to hold—

around you creatures of the ocean

ply their circle dance that swims,

gills flashing, with a darting motion,

lightly on their finny limbs;

and slick-necked pups with blunt round noses,

quicksilver dolphins, lovers of the Muses, 10

Amphitrite’s oceanic kids,

nurslings of the goddess Nereids.

Thanks to you I managed to escape

when I was bobbing aimlessly

in the swells off Sicily,

and you took me up on your arching backs

and ploughed the ocean’s wavy plain

through furrows free from human tracks

and set me down again

in Pelops’ country, on Taenarus’s cape, 20

after double-dealing men

from the seaworthy hollow ship hurled me

into the bruise-dark billows of the sea.

What makes this poem a dithyramb? For the ancients, a dithyramb was a genre of choral song, generally (but not inevitably) associated with Dionysus, danced and sung by a chorus in circular formation. The language was characterized by elaborate compounds straining sense and syntax to convey an ecstatic excitement which no doubt matched the music (think Gerard Manley Hopkins, perhaps). Armand d’Angour suggests convincingly that the dithyrambic “circle dance” was a reform introduced by Lasus of Hermione to make it easier for the chorus to keep time and synchronize their sigmas (avoiding unpleasant hissing sounds). If so, Arion’s original dithyrambic chorus may have lined up in a row, though the present poem clearly incorporates Lasus’ reform. Maurice Bowra thought that Arion’s chorus may have dressed as dolphins while dancing around the singer in the center; there is no evidence for this but I do hope it is correct. The monologue is framed as a hymn to / encomium of Poseidon: the deity is addressed and his attributes described, followed by a narrative more personal to the speaker; in this it works a bit like Sappho fr. 1, but without any concluding prayer / request. As in many of my favorite poems, description is praise.

Later I’ll have occasion to remark on how at least one Hellenistic poet, Posidippus of Pella, depicted Arion’s lyre as having washed up after his death at Alexandria, symbolizing by this what he viewed as the Ptolemaic inheritance of Greek lyric song. This post, however, is about riding dolphins. Yeehaw!

As in many of my favorite poems, description is praise.

For W.B. Yeats the dolphin seems to have been a more exciting substitute for Charon, conveying souls in the opposite direction from Arion’s steed, out of life to death: according to Mrs. Arthur Strong, in Apotheosis and the After Life (quoted in my commentary on Yeats; I didn’t dig up this one), the dolphin is an “emblem of the soul or its transit;” “the dead man — or his soul — might be conveyed thither by boat, or on the back of a sea monster, a dolphin, sea-horse or triton.” Who wouldn’t prefer a living jet-ski to a creaky old ferryboat? In Byzantium, in a scene of Coleridgean creative ferment, we read:

Astraddle on the dolphin’s mire and blood,

Spirit after spirit! The smithies break the flood,

The golden smithies of the Emperor!

Marbles of the dancing floor

Break bitter furies of complexity,

Those images that yet

Fresh images beget,

That dolphin-torn, that gong-tormented sea.

I will stop short of interpreting this—perhaps some brave soul is willing to tackle it in the comments?—but it does seem as if the “dolphin-torn” sea functions as a sort of psychic conductor or medium of transit between Yeats’s spiritual Byzantium and his corporeal Hibernia. In the second part of “News for the Delphic Oracle,” we get another vision of transit, which isn’t quite Wordsworth’s “And see the Children sport upon the shore, / And hear the mighty Waters rolling evermore,” but it’s in the neighborhood. Presumably Yeats’s title puns on Delphi and delphis (“dolphin” in Greek). I wonder if there is something dithyrambic about his emphasis on ecstasy:

Straddling each a dolphin’s back

And steadied by a fin,

Those Innocents re-live their death,

Their wounds open again.

The ecstatic waters laugh because

Their cries are sweet and strange,

Through their ancestral patterns dance,

And the brute dolphins plunge

Until, in some cliff-sheltered bay

Where wades the choir of love

Proffering its sacred laurel crowns,

They pitch their burdens off.

This dolphin-ride will end in Ireland, with a Pushkin translation Seamus Heaney included in Electric Light. Significantly, the story Pushkin tells is different from the one in Herodotus: here Arion’s ship is a victim of storm rather than pirates, with Arion as the only survivor, thanks to his delphine rescuer. In her review in the Irish Times, Helen Vendler suggests that Heaney sees himself as Arion, safe for now on shore, looking out at the mighty waters that have swallowed Hughes, Brodsky, and the rest. Heaney’s muscular trimeter and slanted rhyming feel like an homage to Yeats, though his last line recalls Horace’s escape from (erotic) shipwreck in the Pyrrha Ode, as well as Milton’s translation of that ode, both of which I discuss here. I am not sure if it is specified elsewhere that Arion sings the whole way to shore, like Orpheus’ severed head floating down the Hebrus. What Heaney’s poem most particularly conveys, it seems to me, is a sense of astonishment, not only at his salvation, but also at his own song: Arion is “a mystery to myself.” Whence does this world-harnessing musical witchcraft arise? How and why does it work? The ur-poet doesn’t know, he just goes on singing:

Arion

by Alexander Pushkin [trans. Seamus Heaney]We were all there in the boat;

Some of us tightening sail,

Some at the heave and haul

Of the oars, vessel and load

Deep surging, our passage silent,

The helmsman buoyed at the helm.

And I, taking all for granted,

Sang to the sailors.

A wind

Struck then, a boiling maelstrom.

Helmsman and sailors perished.

Only I, still singing, washed

Ashore by the swell, sing on,

A mystery to myself,

Safe and sound on a rock-shelf

Where my clothes dry in the sun.