On September 4, 1955, 20-year-old Oktan Ekin Faik, a Greek citizen from Komotini employed at the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki, guided King Paul and Queen Frederica through the Turkish pavilion at the Thessaloniki International Fair. The royal couple was reportedly impressed by Faik’s fluent Greek and his status as the first member of the Muslim minority attending the Law School of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Perhaps King Paul saw in him a symbol of Greek-Turkish reconciliation. In reality, Faik was already a loyal agent of Ankara.

The royal couple departed for an official visit to Belgrade, unaware of the crucial and sinister role Faik would play the following day: transporting a bomb from the Greek-Turkish border that would explode in the garden of the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki—a provocation designed to incite violence against Greeks in Istanbul.

A Night of Pogroms

The explosion on the night of September 5–6, 1955, set off a violent mob that looted Greek-owned businesses, homes, and churches across Istanbul. The “Septemvriana,” as the events became known, resulted in the near destruction of the city’s Greek community, which has dwindled to roughly 2,000 people today. Sixteen Greeks and one Armenian were killed, more than 200 women were raped, and many clergy members were tortured or killed.

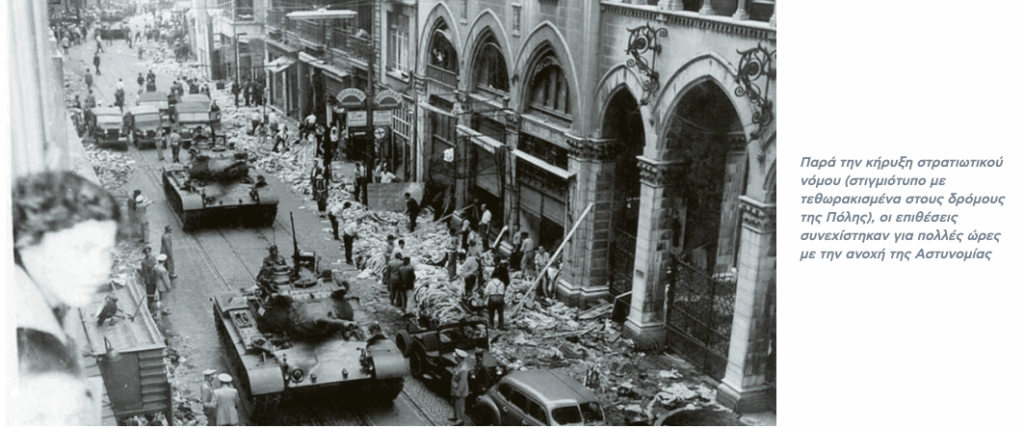

The attacks were meticulously organized. Around 100,000 Turks participated, including 30,000 brought in from surrounding regions, armed with clubs, axes, and even dynamite. Greek homes, schools, churches, and businesses had been pre-selected as targets. Local police largely stood by during the assaults, intervening only after the worst had occurred.

Historical Context

The Septemvriana did not emerge from a vacuum. Greek-Turkish relations were tense, despite both countries having been NATO allies since 1952. Systematic measures had long been used to pressure Istanbul’s Greeks to leave: arbitrary deportations, restrictions on professions, property seizures, and excessive taxation. Between 1947 and 1955, some improvement occurred, with the Greek community revitalizing schools, hospitals, and cultural institutions.

However, the Cyprus issue exacerbated tensions. In April 1955, EOKA launched its campaign for the island’s independence from Britain and eventual union with Greece. Turkey, leveraging the Turkish-Cypriot minority, demanded either control or partition of Cyprus—a policy it continues to pursue. Turkish nationalist organizations, including “Cyprus is Turkish” (Kibris Türktür Cemiyet-KTC), played a central role in preparing and executing the pogrom.

Triggering the Violence

The immediate pretext for the attacks was staged in Thessaloniki. At midnight on September 5–6, a bomb exploded at the Turkish consulate, causing minor damage but symbolically invoking Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern Turkey. Faik transported the bomb, which was planted by a consulate employee loyal to Ankara. Newspapers published exaggerated reports of the damage, inciting mobs in Istanbul, particularly around Taksim Square and Istiklal Avenue.

Destruction and Legacy

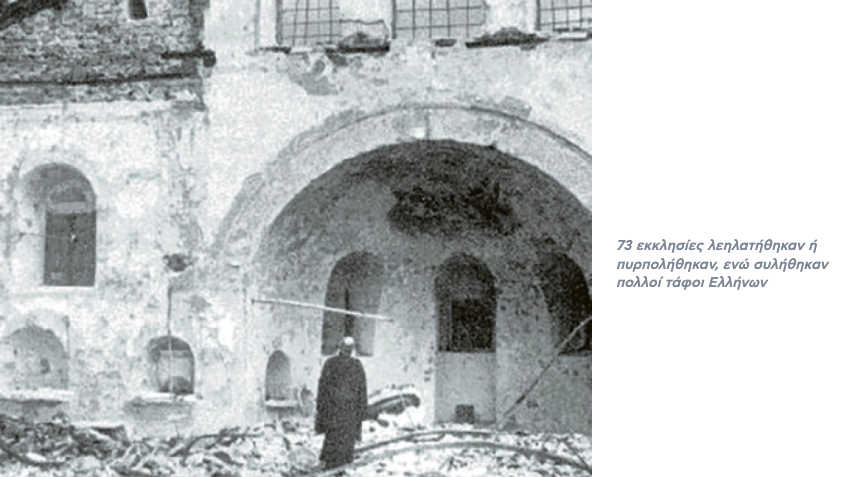

The material damage was staggering: 1,004 homes destroyed, 2,500 more damaged, 4,348 stores, 27 pharmacies, 26 schools, 73 churches looted or burned, and countless cultural sites devastated. Estimates of economic losses vary from 25 million USD (Turkish government) to 2 billion USD in today’s value (Greek estimates). Beyond the financial toll, the pogrom irreversibly diminished Istanbul’s Greek cultural and social presence.

Aftermath

The Turkish government later offered reparations of less than 10 million Turkish lira—less than 1% of the losses. Fear and destruction prompted thousands of Greek citizens to emigrate. Greece’s response was muted due to political instability following the illness of Prime Minister Alexandros Papagos. U.S. diplomatic pressure urged restraint. In 1960, a military coup in Turkey led to trials of 592 officials connected to the Democratic Party, including Prime Minister Adnan Menderes and Foreign Minister Fatin Rüştü Zorlu, who were eventually executed.

The Septemvriana reveal patterns in Turkish-Greek relations: opportunistic aggression against Greece during periods of political instability, exploitation of nationalist sentiment, and the use of organized violence to achieve political goals. The events also highlight the enduring consequences for the Greek community, whose cultural and economic foundations in Istanbul were irreversibly damaged.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions