I was fortunate to have been born in the Deep South during segregation. Not because segregation and racism were in any way good — they weren’t — but because I was able to witness the end of that dark period in the grand American experiment.

Another defining part of my early life was my mother’s commitment to exposing my brothers and me to the arts, especially music. She was a wonderful vocalist, played the piano and organ at church, and was a member of the renowned Robert Shaw Chorale, considered one of the best choral groups in the U.S.

She also had an excellent record collection dating back to the early 1950s. Remarkably, she let me play records on our big hi-fi when I was only 5. I built on that collection, and today I have thousands of records I still play regularly. And yes, I believe, no, I know, playing records sounds better than streaming music.

Our home was filled with the greats — Gershwin, Artie Shaw, Frank Sinatra, Rogers & Hammerstein, and her favorite, Perry Como. We also listened to classical music, not just on the hi-fi, but live. She took me to hear the Atlanta Symphony and the opera.

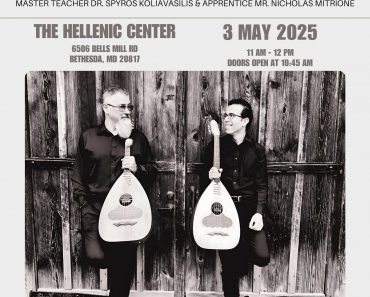

We also listened to Greek music. Urban popular Rembetiko in odd-time signatures featuring bouzouki and clarino, mostly in minor keys. We sang Greek music in the house, listened to records from Greece, and danced the kalamatianos, sousta and zeimpekiko at community holiday celebrations.

By the time I was 14, I had a good ear, could read music and was decent on the sax. But I had no idea I was missing out on an entire world of American music.

I started high school in 1974 with tunes like “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Smoke on the Water,” “Kodachrome,” “Saturday in the Park” and “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet” as the soundtrack of my teenage youth. Get the picture?

1974 was also the first year Atlanta Public Schools were fully integrated. For many of us, it was our first time standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Black classmates, learning, socializing, and most memorably, dancing together.

In high school, I was exposed to the music of my Black peers — Earth, Wind & Fire, The O’Jays, “Boogie Wonderland,” “Back Stabbers,” “Good Times,” “Flashlight” — and better yet, blues and gospel. Music with depth, soul and a rhythm that I’d previously not fully appreciated.

Living through forced desegregation had a profound impact on me. I realized the parallels between my Greek culture and Black culture — family, food, church, music, and arriving at events late, on Greek/Black Time. The same values that defined my Greek-ness also defined my new classmates’ Black-ness with a different feel, language, and beat.

Nothing bridged the gap more than school dances. Imagine kids who had been kept apart, told by society they were not to mix, suddenly in the same gym dancing together. It was magic. A start to the realization of Dr. King’s dream. And to this day, my classmates and I talk about how that shared music helped bring us together.

We also talk about how our kids aren’t able to experience that same magic.

Forty years later, we lament endlessly about systemic racism, microaggressions, equal opportunity and inclusiveness. Yet many parents and grandparents avoid exposing themselves or their children to the most natural form of cultural connection — music.

I see this right here in Park City.

Last year, Lalah Hathaway put on one of the best shows I’ve ever seen at the Eccles. The night started with a killer warmup band, then a DJ who brought the house down, and finally a masterclass in jazz, R&B, hip-hop and pop by Lalah.

Also last year, the Venezuelan vocalist Nella Rojas gave a stunning performance infused with Andalusian roots and Latin pop influences.

This year, in separate concerts, Black Violin and Kings Return took the Eccles stage, delivering genre-bending, unforgettable performances by classically trained violin and acapella vocals.

Every one of these artists received standing ovations. Every one of them is either a Grammy winner or a nominee. Every one of them brought music deeply rooted in their culture.

And every one of them played to a mostly empty Eccles Center.

Experiences like these are opportunities to embrace the magic I felt during desegregation — to expose your family to other cultures, to experience the art that makes those cultures special, and to break down barriers the way music has always done.

So next time you see an artist coming to town representing Black, Native American, Spanish, Argentinian, Persian, Greek or any culture other foreign to your family, buy a ticket. Bring your family. Sit in the audience. Listen and dance.

You just might experience some magic of your own.

Ari Ioannides is a recovering tech entrepreneur, founder of BootUP PD, and serves on local government and nonprofit boards. He offers a conservative perspective on local politics. He can be reached at [email protected]