A new study published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization presents an alternative explanation for how city-states emerged in ancient Greece. Instead of being solely the result of war, geography, or internal politics, the study argues that the true driver of those societies was trade. More specifically, the advantage each city had in producing different goods and how this incentivized exchange, prosperity, but also conflict.

The article, authored by Jordan Adamson, proposes that natural differences between regions, such as the type of vegetation or the availability of certain products, led to productive specializations, which in turn generated wealth through trade, attracted enemies interested in that wealth, and forced communities to organize for self-defense. Thus, the author claims, many Greek poleis may have been born.

Trade based on comparative advantage creates wealth, which attracts attackers and ultimately stimulates defense, Adamson explains.

The key to the study is a simple concept related to the diversity of natural endowments. This means that not all regions had the same conditions for producing the same goods; some were better suited to growing certain crops, others had access to minerals, timber, or other resources, and that diversity created a natural incentive for exchange.

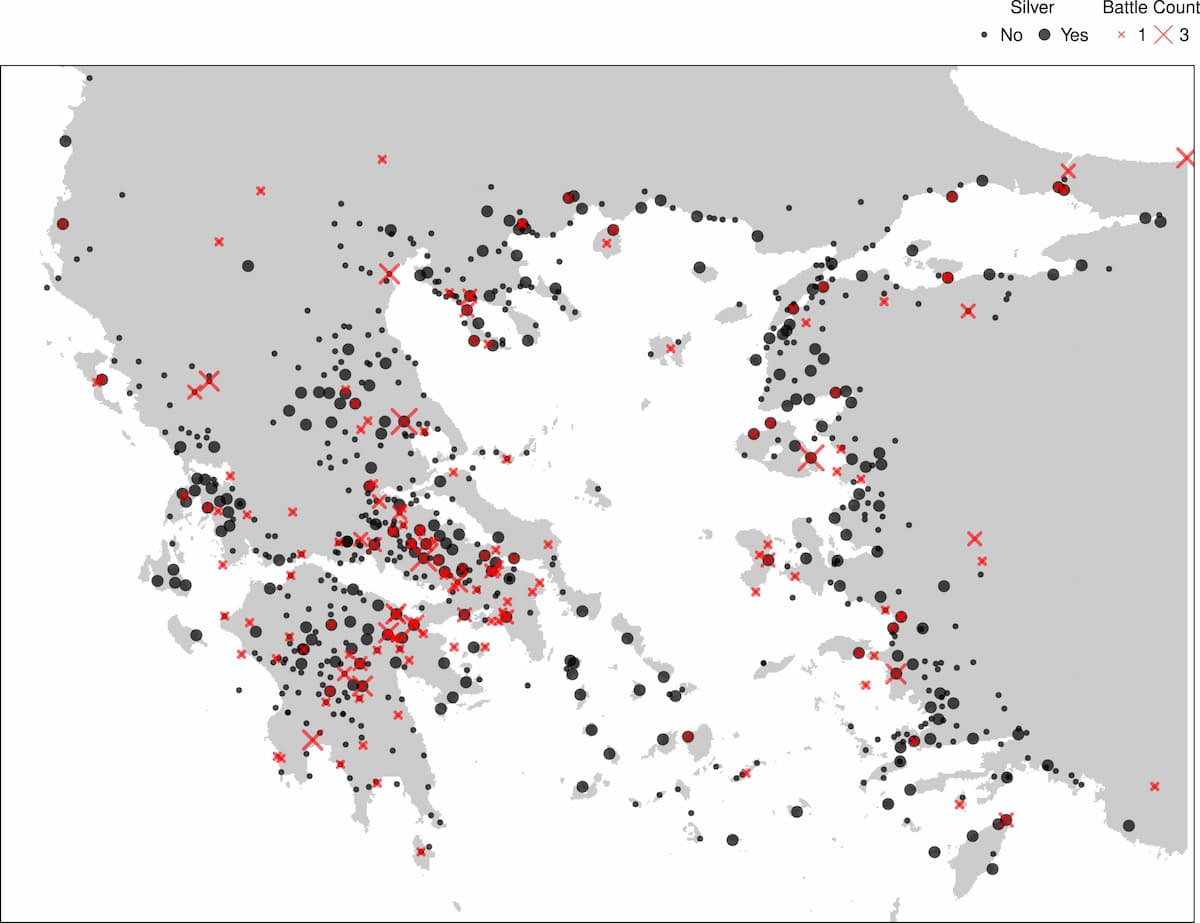

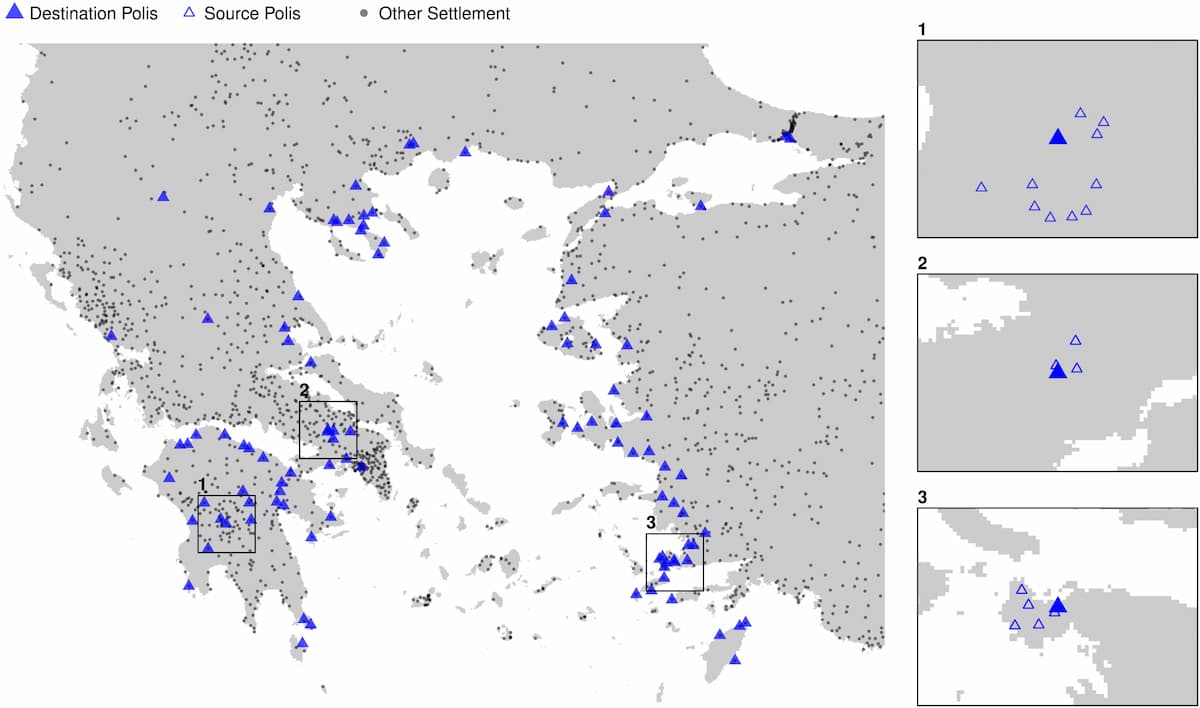

To test this, Adamson built a database of 696 Greek city-states that existed between 600 and 320 BCE. Using historical records, ecological maps, and archaeological data, he identified where these poleis were located, what type of vegetation surrounded them, whether they had minted silver coins (a good indicator of trade), and whether they had been sites of battles or of the unification of villages, what the ancient Greeks called synoikismos.

The results showed that regions with greater variety in natural environments—that is, where there was more contrast between what one city offered and what its neighbors offered—tended to show three things: greater use of coinage, greater involvement in conflict, and a higher likelihood of having formed through synoikismos. According to Adamson, this pattern cannot be explained by the so-called “key factors” emphasized in other studies, such as proximity to the sea, access to rivers, or soil quality.

This suggests that the outcomes associated with city-states are better explained by the diversity of natural endowments than by any previously emphasized ‘key factor’, the author notes.

When Defense Creates Cities

One of the phenomena that receives the most attention in the study is the aforementioned synoikismos, the Greek term that refers to the process by which several villages or communities united, sometimes physically, sometimes politically, to form a new city-state. According to Adamson, this phenomenon can be interpreted as a collective response to a common threat: looting.

A city that grew wealthy through trade automatically became a target for others. That’s why several neighboring communities might decide to unite and concentrate in a single fortified settlement, and this is how cities like Megalopolis emerged, which was founded shortly after a major battle between Sparta and Thebes.

This also allows for a reinterpretation of the causes of ancient wars. The Greeks recognized that the desire for more wealth was often at the root of violence; military force was seen as a natural means of acquiring resources, the author writes, citing historical sources. In other words: they weren’t just territorial disputes, but attacks directed at wealthy and poorly defended places.

Another piece of data analyzed in the study concerns the emergence of silver coinage, which was not common in just any settlement. According to Adamson, its presence indicated that a city was embedded in active trade networks, and indeed, he found that cities with coinage also tended to have been the scene of battles and had often emerged through processes of synoikismos. The minting of silver coins became the universal means of payment in all cities open to trade, the author notes.

The link between trade and violence is thus clearly established: where there is silver, there is interest, and where there is interest, there may be war. But also organization, defense, and institutional growth.

Although the study focuses on ancient Greece, what happened in that corner of the Mediterranean was not unique, according to Adamson. Similar patterns have been observed in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia, and even in the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas. In all these places, trade appears to have been a silent driver of political organization.

SOURCES

Jordan Adamson, Trade and the rise of ancient Greek city-states. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Volume 235, July 2025, 107035. doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2025.107035

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.