International Greek Language Day, celebrated annually on February 9, pays homage to the influence of the Greek language on human civilisation. It is a language that spans over 2,500 years in written form and one that has been spoken for 40 centuries from ancient times until now.

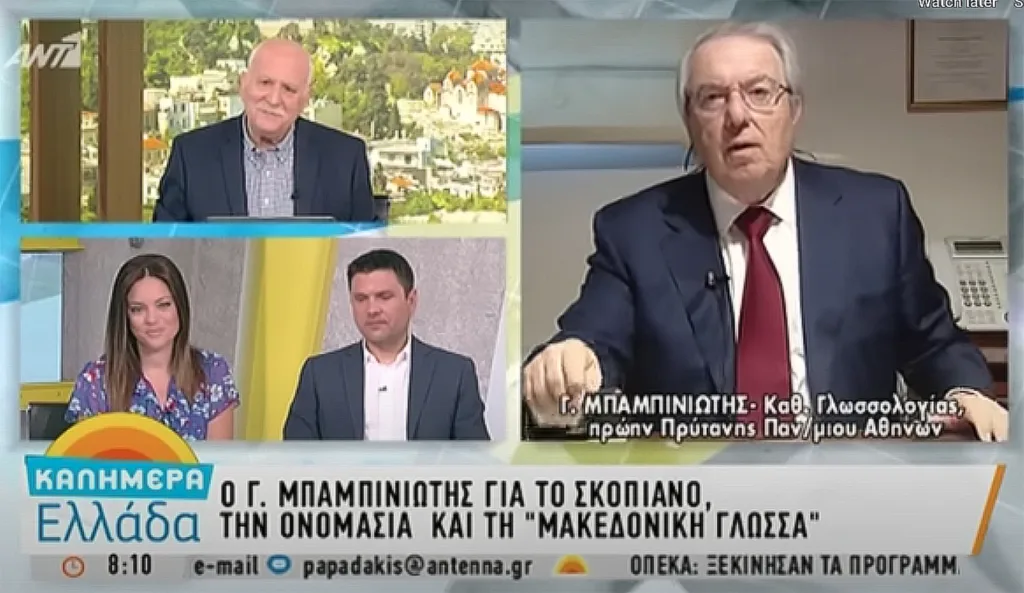

Renowned Greek language expert Professor Giorgos Babiniotis, a man with over 60 years of experience as Professor of Linguistics with emphasis on the Greek language in all its aspects, (including former Rector of the University of Athens, Greece and Minister of Education for a while), who I had the pleasure to meet and speak with, further stressed that the Greek language, although continually evolving since Antiquity, is still directly related to Greek spoken today.

“The Greek language is a continuum from ancient times with a few changes but is nonetheless from the same root. One conversant in Greek now, can still understand Ancient Greek texts… though of course, Greek has evolved, otherwise it would be a frozen, calcified language…”

The choice of the date for International Greek Language Day serves to commemorate famous Greek poet, Dionysios Solomos, who passed away on February 9, 1857. Among other respected works, he wrote the Greek National Anthem, ‘Hymn to Liberty.’

This annual, international tribute to the Greek language began in 2017. Had it begun sooner, it may have perhaps tempered my lack of appreciation for going to ‘Greek’ school every Saturday as a child growing up in Australia.

While my Aussie and other nationality school mates were most likely asleep, or watching cartoons in their pyjamas eating Rice Bubbles or Coco Pops or even crumpets, I was often dragged out of bed on Saturday mornings to be on time for Greek school. In my era, it was in a funky, red-brick Anglican Community building, presided over by teachers fresh from Greece.

Unlike my laid-back teachers at weekday ‘normal’ school in the 70’s and 80’s, these Greek guys were, well… more prone to disciplining us young students. This included hitting our hands with a ruler or pulling our ears! Though I liked learning the language, their tendency towards punishment hampered what could have been a serious love affair with it.

Had Professor Babiniotis’ insights into teaching Greek abroad been known and observed by all involved back then, my learning of Greek may have been more enjoyable and productive.

“Greeks abroad, of the homogeneia – such as Greek Australians, who do not maintain a relationship with the Greek language, have lost the meaning of Greekness, that is why it is crucial that Greek is taught there,” Professor Babiniotis said.

“I am not against having isolated specific day or afternoon schools teaching Greek. I rather don’t agree with exclusively ‘Greek schools’ abroad, as they cannot survive for long in terms of spreading Greek values. I think dual language schools work best whereby, the host country’s language is taught side by side with the Greek language in full syllabus mode with almost equal time given to all subjects in both languages, in English and in Greek in the case of Australia.”

The Professor clarifies why he prefers the term ‘homogeneia’ (which emphasises shared language and religion) rather than ‘diaspora,’ when referring to Greeks abroad.

“Diaspora has specific meaning which originated with the Jewish people being chased out of their homeland; hence signifying the powerful and discerning ideology inherent in the different concepts of the words ‘homogeneia’ and ‘diaspora’,” he explained.

A firm believer in Ancient Greek continuing to be taught in higher level education, he posits: “What is the basis of European civilisation? It is classical Greek thought. It is Roman administration. It is Christianity. Without these, where do you stand as a European?”

During our meeting, Professor Babiniotis really clarified the importance of the Greek language for me. He reinforced this not only on an intellectual level, but also on a deeper emotional one.

He patiently listened, including to some of my perhaps naïve statements and arguments such as, “Greece isn’t doing that great for its people now, particularly for the educated young who flee overseas to earn decent money” and “Greece has such a low birth-rate anyway, so it seems like people are giving up on Greekness, thus what good does meticulously learning the Greek language do?!”

With his responses, Professor Babiniotis helped me to philosophise rather than react. He said, “Greeks tend to exaggerate when they have the majority of their needs fulfilled… so I tend to see such complaints and whining, as a form of ‘creative nagging.’ Luckily, this prevents complacency.”

He enlightens me on the fact that the Greek language is transcendental in a sense.

“It is an active conveyor of values, of principles. It embodies the direct relationship of language with ancestry, with a genealogy of a people. As our mother tongue, it’s what conveys our homogeneity abroad, it signifies our identity. Language is identity. It is our consciousness and this is of utmost importance as a testament to our values in expressing the way we think. This concept isn’t something simple,” he said.

“It’s not what Greeks eat. It’s about where we as Greeks originate from, what we’ve given back to the world. Having Greek heritage is a form of pride; being from a race that historically constitutes the basis of European civilisation, and through European civilisation: Culture.

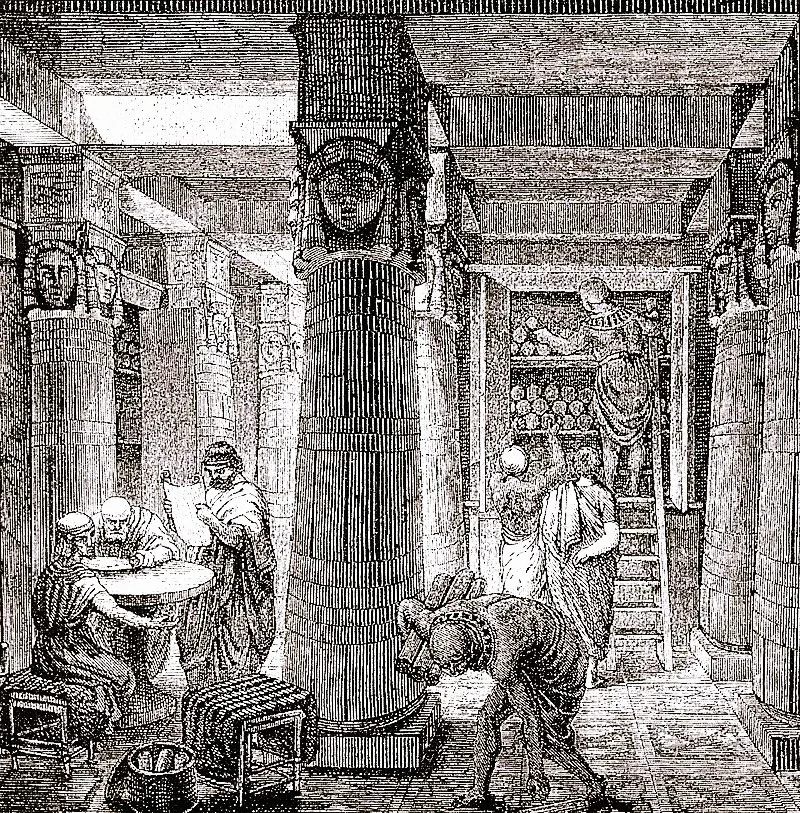

“The Greek culture and/or civilisation is based on the written word, on (keimeno) text as in the writings of the great minds of our Ancient Greek ancestors. Minds such as those of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Aeschylus and many others.

They activated human thought on the big issues, such as democracy, freedom, knowledge; everyday discourse in Ancient Greek culture.”

As Professor Babiniotis continues, I absorb his philosophy about Greek in awe and with a deepening respect for my parents and teachers’ efforts (odd tactics aside), in teaching me Greek.

“The Bible is in Greek, (even the Old Testament was translated into Greek for the many Jews who spoke only Greek – called the Hellenists), as only in Greek could the expression of such difficult concepts of faith be expressed adequately and as succinctly as humanly possible,” the Professor said.

“Christianity continued Ancient Greece’s spirit of humanism, highlighting the overriding values of love and compassion. In the 4th century AD Byzantine, Greek became the official language of Christianity and bridged the Byzantine with Ancient Greece. It was the monks of that time who, even though Christian, managed to copy, and preserve ancient Greek texts such as Homer because they themselves were Greeks who spoke and understood Greek. It was this uniting of Christianity accepting many aspects of Ancient Greek and Greece, such as the monotheism of Plato. Centuries later in the Renaissance we saw a return to an appreciation of Ancient Greek as the utmost expression of culture and civility.

“That which characterised European civilisation came from Ancient Greece, expressed through the Greek language. This was rational thinking (orthos logos), even amongst our culture of mythology. Ours was an anthropocentric view of the world. We weren’t in it purely for ‘happiness’ – a much more complex word and notion expressed in Greek as ‘eytyhia’ which denotes to be lucky (‘tyhi’). We – our Ancient Greek forebears, sought ‘eydaimonia’. The concept of ‘daimon’ meant godly as in questioning to reach a higher plane of moral decency, through rationalising, through knowledge, through effort and study – not something that comes with luck.

“Greek is a cultivated language that has had a lot of work put into it. It describes complex meanings which the Ancients had to find the equivalent words (symbols), syntax and grammar to formulate into text.

“We had Plato’s Symposium where we drank, ate and discussed; ‘syzytisi’ not just conversed.”

Professor Babiniotis explains ‘discussed’ as ‘syzytisi,’ meaning ‘syn’ and ‘zitisi’ as ‘the search for truth’ in common. He stresses its deeper context than just as a meeting to have a conversation, which comes from the Latin ‘conventus’ – to convene – which denotes to meet. Unfortunately, often describing these concepts in English tends to suffer from getting ‘lost in translation.’

He highlights that Greek speakers today can understand these concepts, like they can ‘politics,’ which comes from the word ‘polis’ – state or city. Apart from a purely linguistic and etymological point of interest, Professor Babiniotis brings up such examples to stress that today’s Greek is a continuation of Ancient Greek.

An avid writer in his field, which includes 10 dictionaries and many other works, the Professor, now 86, revealed to me that he is writing another book on the theory of language.

From his work, he has ascertained “around 80% of modern Greek words are from Ancient Greek.”

“We are linked by tradition, by history. We may not be the only ancient language, as there is Chinese, Indian and Egyptian for example, but their modern peoples do not understand their ancient texts or tongues, as we Greeks do. We, who can pick up a book of Homer or Thucydides and understand it more or less,” he added.

“The English language is easier. It has more monosyllabic words and when it wants to describe something more complex, it takes this from Greek or Latin, for example, discourse, discovery, not to mention medical and other scientific terminology.”

Professor Babiniotis also touches upon our internet age of high speed. He refers to the influx of information which is difficult to succinctly process, let alone convert to rational thought and ensuing eloquent language expression, leading to ‘brain rot.’

“The importance in communication is in getting from the concept of ‘what‘ is said into ‘how‘ it is said: How you will express yourself through language? This is the test, and due to the fact that you select the way to express your thoughts, this is where our freedom lies – in how we express what we think. Otherwise we would ourselves become automatons, robot-like, whereby our definitive human faculty of individual thought would be diminished, and we would become sad creatures,” the Professor stressed.

In closing – though Professor Babiniotis will never and could never close in terms of his passion for the Greek language and its teaching – he said, “I consider Greek International Language Day, celebrated on February 9, as essentially a celebration of European civilisation. Language is not a tool, it is a value system, it is history, it is culture.”

As for me, I have humbly learned that the Greek language is the finest embodiment of human thought, and I am a now a very proud and grateful benefactor of this knowledge and wisdom. Thank you, Professor Babiniotis.