Eighty-four years ago, a dark chapter unfolded in modern Greek history—the invasion, or “entry,” of German troops into Athens and the raising of the swastika atop the Acropolis, following the lowering of the Greek flag. This dramatic moment followed the controversial surrender by General Georgios Tsolakoglou, a subject we’ll explore soon. It was marked by the collapse of the front lines, the departure of King George II and his government to Crete, and the hasty withdrawal of British forces stationed in Greece to the Eastern Mediterranean. Let’s revisit the events that led to this fateful day.

The Collapse of the Front after Tsolakoglou’s Surrender

At 6:00 PM on April 20, 1941, in Votonosi, near Ioannina—10 km from Metsovo and 40 km from Ioannina—Lieutenant General Tsolakoglou and Brigadier General Sepp Dietrich of the LSSAH signed an armistice protocol with terms favorable to Greece. However, the Italian intervention complicated matters further. The final agreement was signed in Thessaloniki on April 23, 1941, by Tsolakoglou, General Jodl, and Italian representative Ferrero.

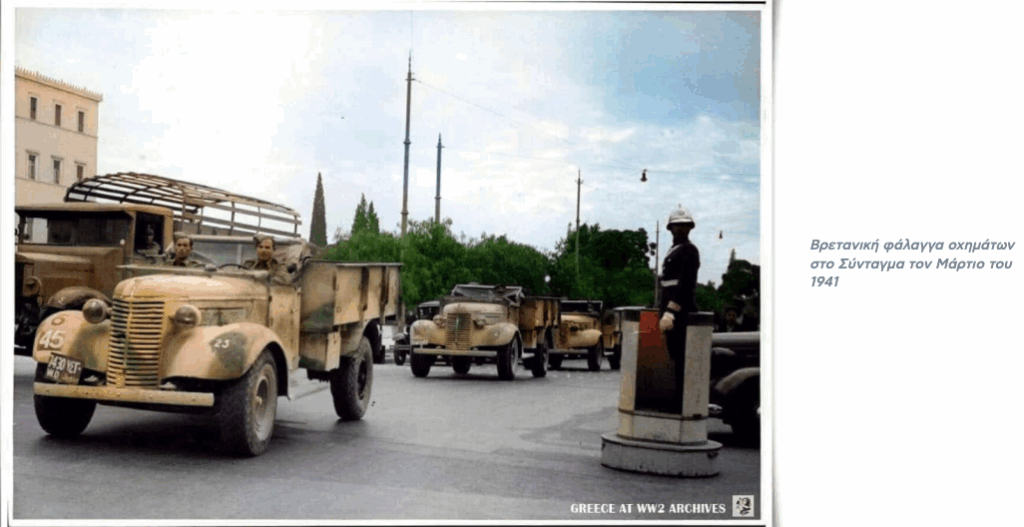

Meanwhile, on April 22, the Germans attacked the Thermopylae Pass, defended by the 19th Australian Brigade and the 6th New Zealand Brigade. By a cruel twist of fate, the commander of the forces at the coastal pass was New Zealand General Freyberg, who evacuated to Crete after the Germans seized Thermopylae. As we have discussed in previous articles, Freyberg bears considerable responsibility for the capture of the large island. Nevertheless, after Crete, he went on to the North African campaign, where he achieved significant successes.

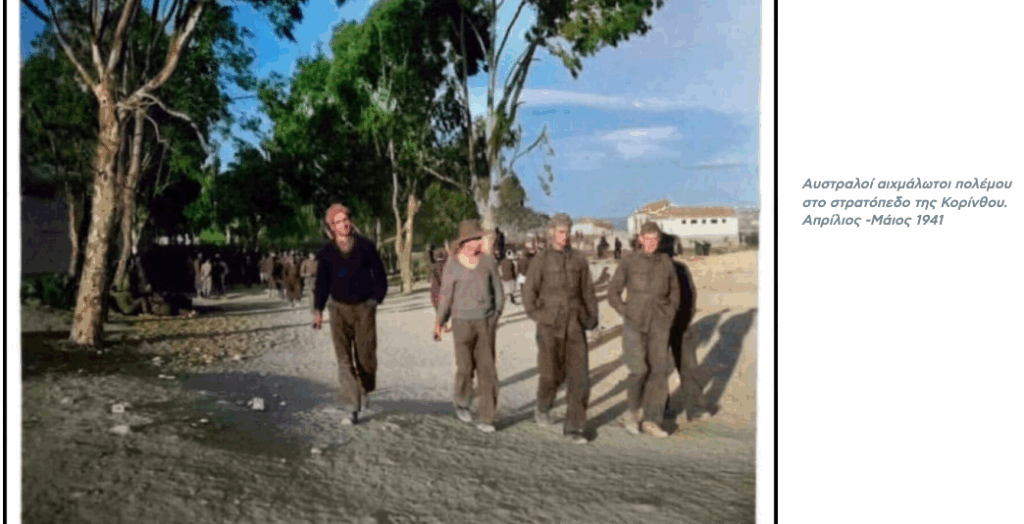

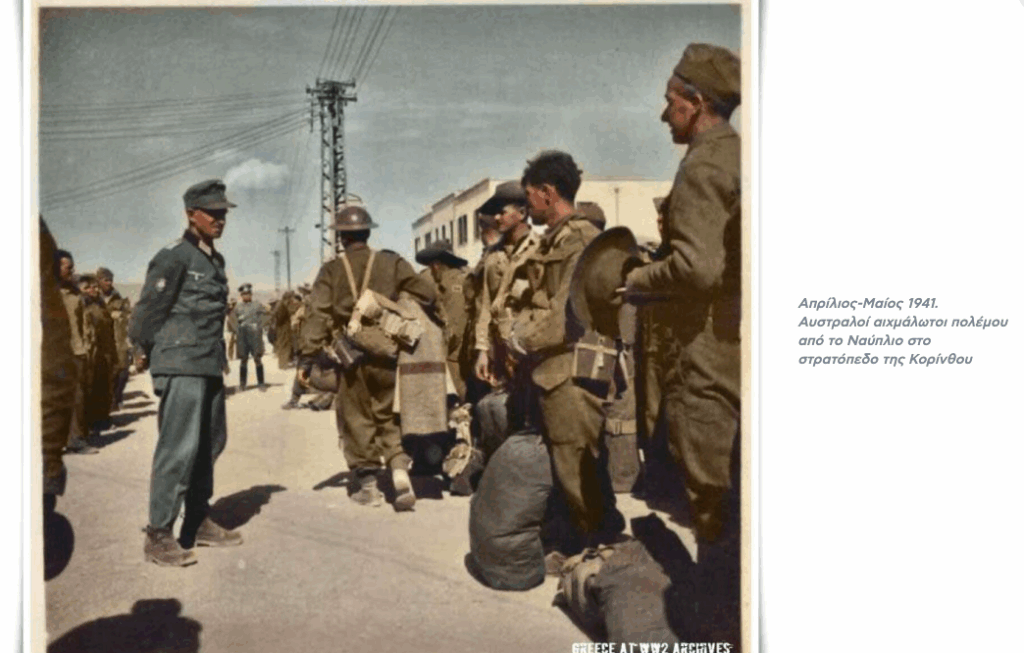

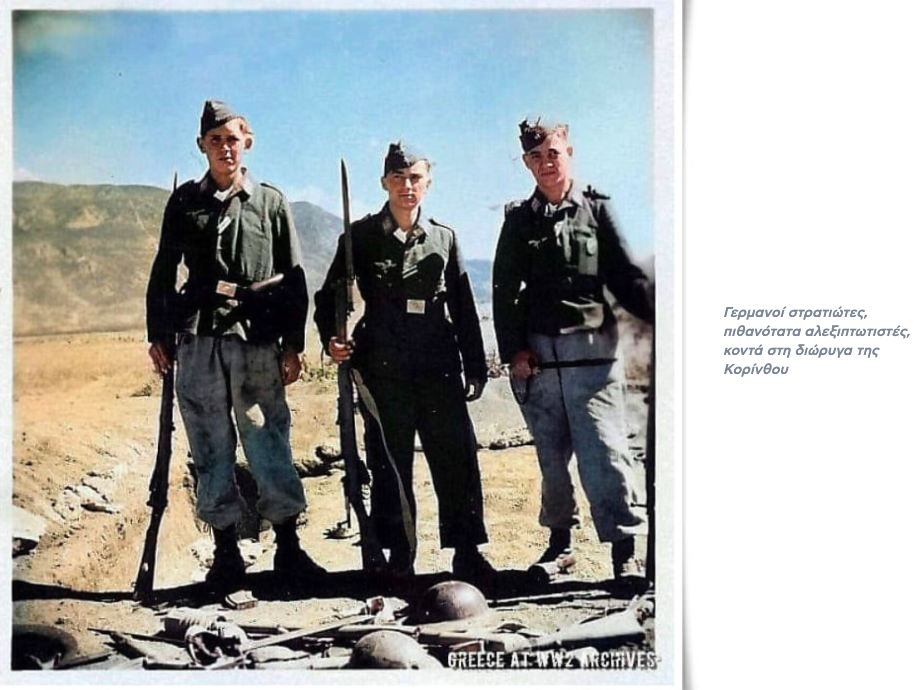

The last bastion for British forces was the Corinth Canal, defended by the 4th Hussars, Australians, and Maoris. British Commonwealth forces had undermined the bridge with explosives, knowing they would face fierce resistance. The Germans, aware of this formidable challenge, deployed the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 2nd Parachute Regiment. After grueling clashes, during which the bridge was destroyed—either during the battle or deliberately by the British as German sappers attempted to neutralize the explosives—the British forces retreated inland to the Peloponnese. With the assistance of local Greeks, they made their way to the ports of Monemvasia and Kalamata, where they sought evacuation by ship to the Middle East and North Africa.

The Departure of King George II and His Government to Crete

On April 22, 1941, most government members departed for Crete aboard the destroyer “Queen Olga.” The following day, King George II and the British Ambassador evacuated by air. For a few more days, Deputy Prime Minister Admiral Sakellariou, Minister Maniadakis, General T.G.G. Heywood, and the British Naval Attaché Captain Terl remained in Athens, leaving on April 27.

Commander Papagos refused to leave, “sharing the fate of his men,” writes Dr. I.S. Papafloratos, continuing, “It was a brave decision, knowing that the Germans were well aware he was not among those enamored with their military superiority, which abounded among the higher military circles. Nevertheless, the Germans did not arrest him, but placed him under close surveillance.”

Papagos, feeling his orders had been violated, submitted a resignation request on April 23, 1941, declaring, “Because the army under my command surrendered against my orders and without my authorization, I submit a request for retirement.” Before this, on April 21, he had issued a strong directive to the commander of the Epirus Army Corps, criticizing Tsolakoglou, emphasizing that the army must fight to the last of its capabilities, and demanded Tsolakoglou’s immediate replacement. Notably, on April 18, Prime Minister Koryzis had committed suicide in Athens.

On April 23, King George II addressed the Greek people, concluding with a defiant message: “Do not be discouraged, Greeks, not even in this painful moment in our history. I will always be among you. The justice of our struggle and God will assist us, as we strive by all means to achieve final victory amid the trials, sorrows, and dangers that we face together. Remain loyal to the idea of a united, indivisible, and free homeland. Strengthen your wills. Stand proudly against enemy violence and temptations. Be brave. Better days will return. Long live the Nation!”

The Nazis in Athens (April 27, 1941)

On the morning of Sunday, April 27, (Thomas Sunday), very few Athenians were on the streets. Despite the significant religious holiday, only a handful of worshippers attended church services. The radio broadcast the Divine Liturgy, when suddenly it interrupted to air the following urgent announcement from the city’s military commander, Major General Kavrakos.

“Due to pressing necessity, I order all movement in the streets of Athens, Piraeus, and the suburbs to cease. All shops must remain closed, and residents are to stay in their homes, while officers and soldiers remain in their barracks and police at their stations. I forbid the emergency publication of newspapers. Since the city is unfortified, no resistance will be offered. I demand that not a single shot be fired. Those who violate this order will be immediately arrested and imprisoned securely. I designate Colonel Pezopoulos as my deputy during my absence.”

Silence reigned in the city. The last British soldiers detonated an ammunition depot in Piraeus. In Athens, only the Nomarch of Attica and Boeotia, Konstantinos Pezopoulos, Mayor Ambrosios Plytas, and the fortress commander remained on behalf of the authorities. They formed a committee that included the Mayor of Piraeus, Michail Manouskos, and German-speaking Colonel Konstantinos Kanellopoulos. The Archbishop of Athens, Chrysanthos, refused to participate.

The committee members surrendered the unfortified Athens to the Nazis after prior discussions with the German military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel von Hohenberg. They awaited the German leader at the intersection of Kifisias Avenue and Alexandras Avenue from 8:30 AM. Colonel Otto von Seiben arrived at 10:15 AM, accompanied by his aides, and approached the committee members. After a military salute, he awaited the military attaché’s introduction.

All attendees, red with emotion and anxiety, lowered their heads in anticipation of the formal handshake. Colonel von Seiben greeted them and suggested they sit at the nearby café “Parthenon.” Many silent Athenians observed the dramatic scene unfold.

Kavrakos smoked incessantly to mask his nerves. Ultimately, he addressed the German officer, while Kanellopoulos translated the following text into German: “The local military and political authorities, composed of General Kavrakos Christos, Senior Military Commander of Attica and Boeotia, Pezopoulos Konstantinos, Nomarch of Attica and Boeotia, Plytas Ambrosios, Mayor of Athens, and Manouskos Michail, Mayor of Piraeus, declare to the commander of the German troops that the cities of Athens are unfortified and will offer no resistance to occupation. All necessary measures have already been taken on our part to ensure order until the entrance of the Germans.”

The German officer responded in kind, praising Greek culture and emphasizing, “I assure you that the German army comes not as an enemy but as a friend, bringing peace to Greece. The long friendship that connects us with Greece will be rekindled in a few days.” Shortly thereafter, the surrender protocol was signed, and Plytas symbolically presented the key of the city to the German officer.

Afterwards, von Seiben called the commanders of smaller units and pointed out to them on a map where they should head, scheduling a new meeting with Plytas at noon. The final announcement from the Athens Radio Station, penned by Dimitrios Svovolopoulos, father of the late academic Konstantinos Svovolopoulos, and read by Konstantinos Stauroupoulos, remains particularly chilling in history.

The announcement’s closing lines are especially memorable: “Attention! The Athens Radio Station will soon cease to be Greek. It will become German and will broadcast lies! Greeks! Do not listen to it! Our fight continues and will continue until the final victory. Long live the Greek nation!”

Eyewitness Accounts of the German Invasion of Athens

In his book “THE GERMAN INVASION OF GREECE—THE FORGOTTEN ‘NO’” (HISTORICAL QUEST Publishing), Nikos Giannopoulos recounts that after the British abandoned the Thermopylae defensive line, the Germans advanced towards Attica. Leading them was a reconnaissance battalion with motorcyclists and vehicles from the 2nd Armored Division, which had moved from Magnesia to Northern Euboea, then to Chalkida, before transitioning to Central Greece, arriving outside of Athens.

Just after midnight on April 26-27, 1941, the last British forces left Athens. Andreas Stamatopoulos, an eyewitness, was in Athens with his family. They stayed at the “City Palace” hotel on Stadiou Street. As Giannopoulos recounts, according to Stamatopoulos, once all British vehicles departed the city, total silence prevailed until 2:30 AM. From 2:30 AM to 4:00 AM, sporadic military vehicle movement occurred.

People were restless, peering out from behind closed shutters, filled with anxiety. Around 8 AM, Stamatopoulos heard the sound of a motorcycle outside the hotel: “A gray military motorcycle, bearing a red flag with the visible black swastika folded behind the driver’s seat, sped from Omonia Square towards Syntagma. Suddenly, we all felt a lump in our throats. We were now under occupation…”

Indeed, at 8:00 AM on Sunday, April 27, 1941, motorcycles and armored vehicles from the 2nd Armored Division, led by Lieutenant Fritz Dirfling, entered Athens from the northern suburbs. Nikos Tsertsos saw the first vehicles at America Square: “They drove BMW motorcycles with sidecars and machine guns. Following were lightly armored vehicles, with the German flag mounted on the hood for identification.” “It happened to be a cloudy, grim day,” recalls Ioannis Antonakeas.

Thirteen-year-old Iakovos Vagiakis watched a German mechanized column from the slats of his window. Upon reaching Kaningos Square, which then featured circular traffic, they stopped. The soldiers rushed into the orange trees that surrounded the square, picking oranges and starting to eat them, perhaps mistaking them for sweet oranges! Helene Frangia, a sector leader of the EON, stated: “The order from EON’s central command was to greet them with our silence and to close ourselves in our homes… Athens was a dead city; no windows were open, and there was no one on the street. Shutters were closed. We heard through the windows the boots, the tank, and the motorcycle of the invader.”

Vasilis Kouroupos was then living in Psiri: “We heard the Germans descending Ermou Street. We cried with the windows and doors shut.” The late Leonidas Kyrkos, in his last interview with Nikos Giannopoulos, recounted the first sound of the occupiers: “Locked in our homes, behind the windows, we heard the boots of the Germans pounding on the street. This was the first memory of the Occupation.” A young Nikolaos Pavlioglou described a scene he witnessed on University Street: “The streets were almost empty, with very few people around. There were a few who applauded, but they were of German descent.”

Nikos Tsertsos reflected on Patision Street: “They arrived from Tatou. There was no crowd, no applause, nothing, unlike Paris.” Nonetheless, both were struck by the appearance of the Germans: “They were beasts darkened by hardship. Unsmiling and silent” (N. Pavlioglou). “Rugged, darkened by dust, they were warriors. They immediately made an impression and instilled fear” (N. Tsertsos). Stathis Tournakis, who encountered German motorcyclists as he returned home to Plaka from Makriyanni, emphasized their impact: “They were soldiers. Until then, we had become used to seeing disheveled Italian prisoners. The Germans, even as prisoners, did not appear like that at all.”

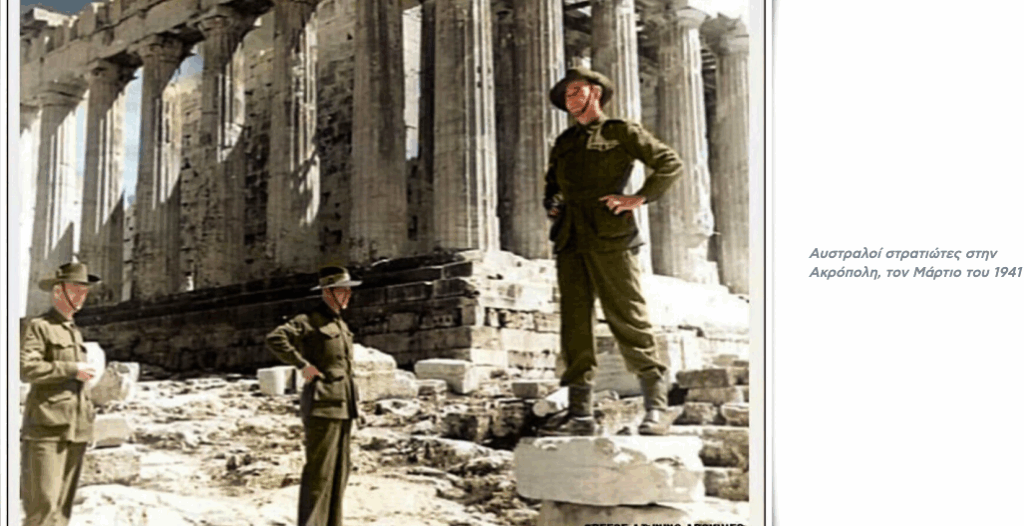

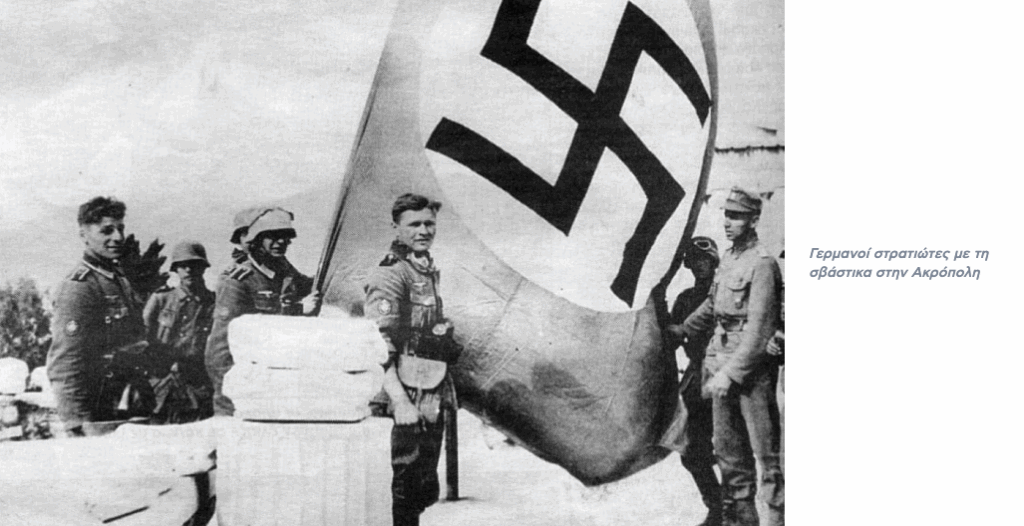

Just before 9:00 AM, men from another German motorized detachment under Captain Jacobi reached the Acropolis’s Propylaea and raised the German flag (swastika) on the Sacred Rock after the Greek flag had been lowered. It was a black moment in Greek history. Helene Frangia recalled: “They went to the Acropolis, took down the flag, and raised the swastika. This was a wound for us.”

When the Germans entered Athens, Penelope Delta attempted suicide by poison. She eventually died on May 2. She never overcame her unfulfilled love for Ion Dragoumis, and her illness (multiple sclerosis) made her life difficult. Her national sentiments also played a role. After all, she had prophetically written: “In the world, there are things, ideas, principles, ideals, beliefs that weigh heavier than life.” Still, that rebellious Greek spirit immediately sprang into action. As the late Manolis Glezos recounted, by that evening, the Germans had set up signposts. However, that night, he and others destroyed them. The next morning, when a German unit arrived at the intersection of Iera Odos and Constantinople, they did not know where to go…

Epilogue

Ultimately, the last city in mainland Greece to fall into German hands was Kalamata after a fierce battle with the British on April 28, 1941. In a speech at the Reichstag on May 4, 1941, Hitler stated: “Before history, I must recognize that, of all our adversaries thus far, the Greek soldier fought with extraordinary courage and surrendered only when all resistance became impossible and senseless. Therefore, I have decided that no Greek soldier should be held captive, and that officers should retain their personal weapons.”

Sources: Dr. Ioannis S. Papafloratos, “The History of the Greek Army 1833-1949,” SAKKOULAS Publications, 2014; Nikos Giannopoulos, “THE GERMAN INVASION OF GREECE – THE FORGOTTEN ‘NO’,” HISTORICAL QUEST Publications, 2015.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions