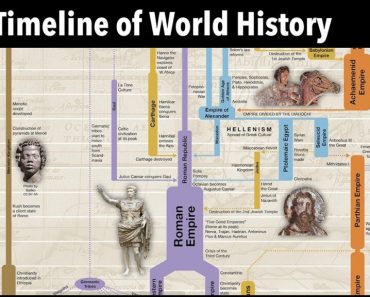

Near the end of the 6th century BC, a strange marriage contest on the Greek mainland set off a chain of events that no one present could possibly have understood, ultimately leading—through a legendary drunken dance—to the birth of the Athenian democracy.

Cleisthenes, the tyrant of Sicyon (near modern-day Kiato, near Corinth), announced that he was looking for a husband for his daughter, Agariste, and that only the finest man in all of Greece would do. On the surface, it appeared to be a traditional aristocratic custom, where a powerful ruler displayed his wealth and status, but the event was destined to become far more consequential than anyone expected.

A tyrant with big plans

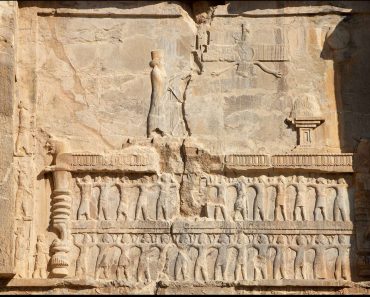

Cleisthenes ruled Sicyon, a thriving city-state in the northern Peloponnese, in the early 6th century BC. As a leading member of the Orthagoras dynasty, he built his reputation through contested politics and military success, including an important role in the First Sacred War on the side of Delphi against Crissa.

Victorious, rich, and highly respected, Cleisthenes began to think about his legacy and, naturally, about his daughter’s marriage. Cleisthenes publicly declared that she would go only to the best of the Greeks. By tying his family to one of the most prestigious families in Greece, he could pull Sicyon into the center of the Greek world and make sure that his daughter shared a household with a man whose rank and influence matched his own ambitions.

The contest begins: The drunken dance that shaped Athenian democracy

Cleisthenes chose his stage carefully, announcing the contest at one of the great Panhellenic festivals, either the Olympic or the Pythian Games. News traveled quickly, and his invitation was simple: within sixty days, any young man of noble birth and proven excellence could come to Sicyon and compete for Agariste’s hand.

The response was impressive. Herodotus tells us that suitors traveled from all over the Greek world: wealthy cities, such as Sybaris and Siris, from Magna Graecia in Italy sent men like Smindyrides and Damasus, while others arrived from Ionia and distant colonies like Trapezus and Epidamnus. Each believed he was a worthy representative of Greek aristocratic virtue, but two Athenians soon drew special attention: Megacles of the Alcmaeonid family and Hippocleides, both from powerful and prestigious Athenian lineages.

Cleisthenes had survived in power long enough to know that appearances could be deceiving, and he was determined not to choose his son-in-law based purely on looks or reputation. He had a racetrack and wrestling grounds constructed, turned his city into a long-running festival, and spent months observing the suitors compete.

They raced, wrestled, trained in the gymnasium, dined at his table, and talked at length under his watchful eye, while he quietly studied their behavior. Herodotus emphasizes that Cleisthenes cared about how the men behaved at meals, how they spoke, how they handled wine, and how they treated others. Through this slow, deliberate competition, the men gradually sorted themselves out, and the two Athenians, Megacles and Hippocleides, stood out as the most impressive candidates in a series of events that would culminate in the legendary drunken dance that would, in turn, accidentally give rise of Athenian democracy.

The feast that started the domino effect

At last, Cleisthenes held his final lavish banquet. He reportedly sacrificed one hundred oxen, filled the tables with food, and ensured that wine was abundant, turning the evening into a spectacular display of wealth and hospitality. After everyone had eaten, he announced two final competitions: one in speaking and storytelling, and another to showcase each man’s taste and skill in music.

In both contests, Hippocleides stood out as the dominant one. His speech, wit, and manner impressed everyone, and he exuded an easy charm and a polished appreciation for music that made him seem every inch the ideal aristocratic son-in-law. As the evening progressed and the wine flowed freely, Cleisthenes found himself leaning ever more toward Hippocleides, imagining him as the future husband of Agariste. But then came the moment that undid it all.

At some point, the wine got the best of Hippocleides. Fired up by the music and his own ego, he decided to entertain the company with a dance. But instead of staying on the floor, he climbed onto a table and performed a series of increasingly wild and showy moves: first a Laconian style, then an Attic one, and finally a personal, improvisational routine that pushed the limits of propriety.

The performance ended with a particularly shocking twist: Hippocleides stood on his head, legs kicking with the music, accidentally exposing himself to the assembled guests and to Cleisthenes. For a man courting a tyrant’s daughter, this was more than just bad manners—it was a stunning display of shameless carelessness. This infamous drunken dance would become legendary, both for its audacity and for the way it indirectly molded the future of Athenian democracy.

Cleisthenes was furious. Any admiration he had felt for Hippocleides evaporated as he witnessed the spectacle, and he announced that Hippocleides would certainly not be marrying his daughter. Hippocleides, already beyond shame, reportedly replied with the line that echoed through Greek proverb: “Hippocleides doesn’t care” (Ού φροντίς Ιπποκελίδη – Ou frontis Hippocleidi), words that came to symbolize total indifference to disgrace or consequences.

With Hippocleides eliminated by his own recklessness, Cleisthenes turned to the other Athenian, Megacles, who had shown composure and dignity. He came from the influential Alcmaeonid clan that already played a prominent role in Athenian affairs. Cleisthenes offered Agariste to Megacles, sent the rejected suitors home with generous silver gifts, and concluded the contest that had captivated the Greek world.

How this night gave birth to Athenian democracy through a drunken dance

The real significance of Agariste’s wedding to Megacles can only be comprehended in light of what followed. Agariste and Megacles had a son, another Cleisthenes, who was raised in a family with aristocratic pedigree, political know-how, and ambition. These elements shaped how Cleisthenes of Athens thought about power, instilling in him a sense of both the dangers of tyranny and the potential for completely redesigning Athens. In a way, the infamous drunken dance that had determined his parents’ marriage indirectly set the stage for the rise of Athenian democracy.

By the late 6th century BC, Athens was simmering with tension, and Cleisthenes of Athens stepped in. Drawing on his family’s wealth, networks, and well-established reputation, he positioned himself as a spokesman for the broader populace, outflanking his aristocratic opponents and introducing something genuinely new. He established a political system that loosened the direct grip of aristocracy and offered people more power than ever before. Thus, Athenian democracy began to take root, shaped by a chain of events that had started with a lavish contest and a fateful drunken dance.