Why did only 196 students complete VCE Greek in 2023? Why has the Greek language (dare I say Hellenism/Romiosini itself) seemingly died out so much in Melbourne? Constantly we say that our cultural clubs and institutions are doing well; we love to pat ourselves on the back about standing up for our heritage and yet still I hear year on year how the language is slowly dying out in the diaspora.

The importance of the Greek language in maintaining our history and culture cannot be understated. Language being the primary medium of communication between people, it is by far the most effective way to learn and interact with Greek art, culture and people. It’s one thing to read a translation of Roza sung by Dimitris Mitropanos for literal meaning, but to implicitly understand the words as they’re sung creates a stronger emotional connection to the music. Language and culture are inextricably linked. Both influence the development of the other – take as an example the Inuit having as many as 52 words for snow, showing how deeply their culture connected to the land they live on. Knowing this, I ask myself the question: are we suffering a crisis of education… or cultural relevance?

Let’s first analyse the numbers regarding what seems to be people’s favourite metric, students completing VCE Greek.

What is happening in VCE?

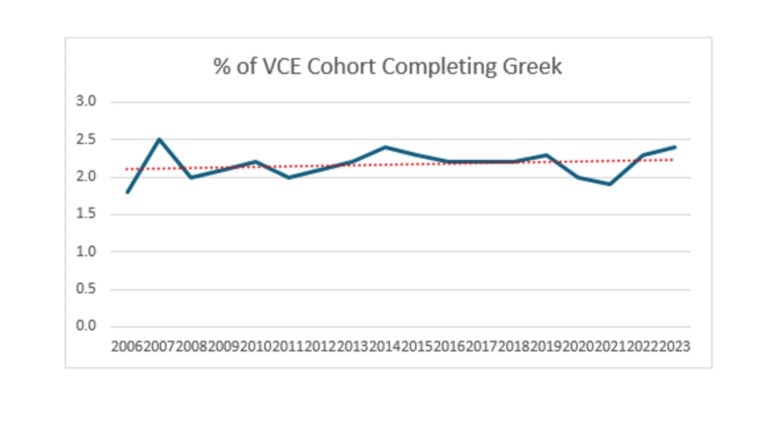

The number of students completing Unit 4 VCE Greek, relative to the amount of overall VCE students in the same year, (at least from 2006) has remained relatively consistent. The lowest recorded number I could find was 1.8 per cent of VCE students in 2006, the most recent percentage I found was 2.4 per cent in 2023 (only 0.1 per cent lower than the 2.5 per cent peak in 2007.) This leaves us with an average of 2.2 per cent. [1]

Here is a graph of the numbers I just quoted year on year, the dotted orange line shows a linear trend showing a slight projected increase in relative interest in studying Greek. (Although not enough to be significant.)

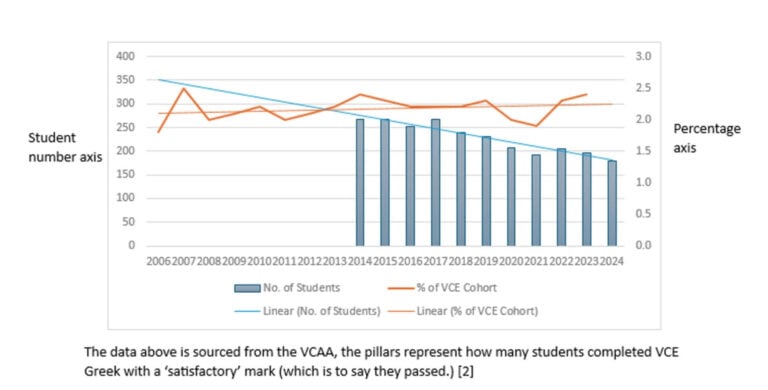

This is not to say that there hasn’t been a decrease in the number of VCE Greek students. Below we can see the number of Greek students studying VCE Greek year on year with a linear trend line clearly projecting the pattern to continue. (The previous percentage graph is overlayed in orange.)

The data above is sourced from the VCAA, the pillars represent how many students completed VCE Greek with a ‘satisfactory’ mark (which is to say they passed.) [2]

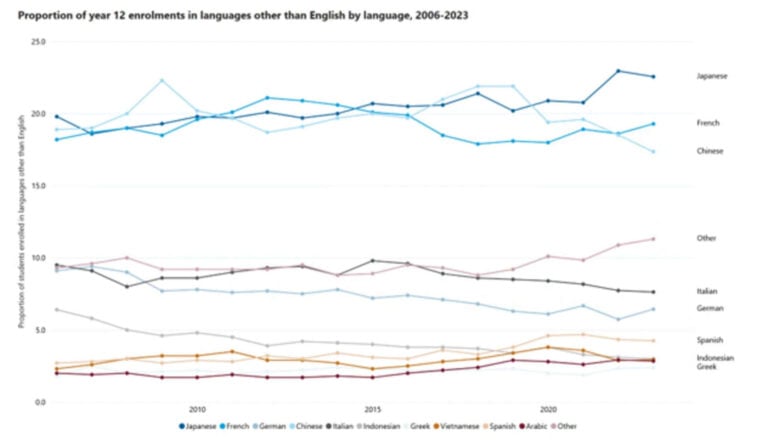

Looking at proportion of students enrolled in all languages [1] we can see that Greek has remained more consistent than many languages. Our Italian brethren seem to be trending downwards slightly (at least doing worse than us) and Chinese Mandarin study, interestingly, has also markedly dropped in recent years.

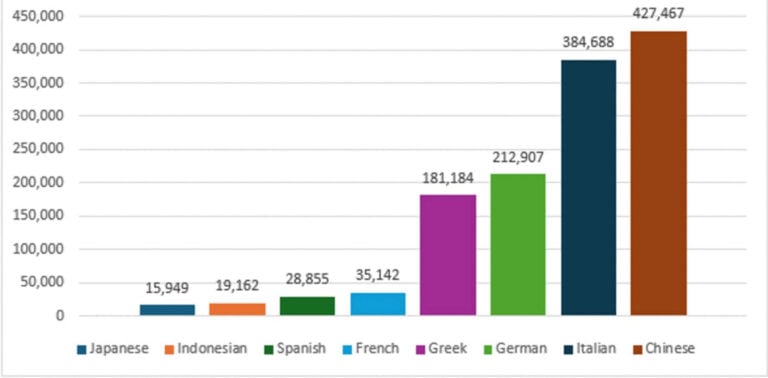

Interestingly, if we look at the 2021 census [3] for Victorian population with these cultural backgrounds we can observe that there is not a strong correlation between population and percentage of students formally studying the language in VCE.

Of the 8 languages that have the largest proportion of completion in VCE, Japanese has ranked the highest since 2019 and has been in the top 3 since 2006. All this despite having the smallest population in Victoria out of all of these languages and by no small margin!

While I do not believe that the completion of VCE Greek is necessarily indicative of how well the language is maintained in Melbourne, I do think that this data presents an indication as to what motivates people towards learning a language.

This leads me to the contention of this essay.

Are we missing the forest from the trees?

For the most part, people make choices that result in actions for some form of reason. To clarify what I mean, let’s say that I chose to study physics because I knew that in university I wanted to end up in engineering. My Greek friend studied Mandarin because his parents believed that since China is Australia’s biggest trading partner, he’s likely to use some of his Chinese skills later in life. Yet this same friend can barely hold a conversation with me in Greek. Even his parents, who are relatively fluent, will only speak to me in English despite me futilely only responding in Greek. Why is this?

People will only bother to learn a language if they believe it will be of value to them. I believe that the relevance of a language falls into one of two categories. Either, the language of a country economically or, more accurately, politically relevant (languages such as English or Mandarin). People want to learn the language for material and practical reasons, such as my friend. Alternatively, the culture which a language is tied to can become relevant instead. I believe that such is the case regarding Japanese. Young people aren’t learning Japanese because they think the language is going to be particularly useful in terms of career prospects. They are learning the language because Japanese cultural exports have had a strong effect on western pop culture and they want to gain a better understanding of Japan’s history and culture of their own volition. This is often most effectively achieved by studying the language itself.

So where does this leave us?

It feels safer to bet the entire Greek treasury on a game of blackjack than to rely on the Greek government to make Greece geopolitically or economically relevant. It would be a similar folly to rely on Greece to help us reignite interest in our language. But cultural relevance is within our control, albeit perhaps not to the extent of the Japanese.

So, I ask myself: what is it about our culture, or the way it is presented, that needs to be changed in order to appeal to younger generations?

This leads to the next question. What actually is our culture at this stage in history? Especially as Australians living so far away from Greece. Not having the hubris to answer this on my own, I interviewed 25 people between the ages of 19 and 29 and asked them what being Greek means to them, why they chose to get involved in the Greek community and other relevant questions on how they relate to the language. Almost all of them are young leaders within the Greek community, involved in organisations such as NUGAS or local Greek youth committees.

What IS a Greek Australian?

Given the limited sample size, it must be acknowledged that any observed patterns lack the robustness required for academic rigour.

There was surprisingly little variety in the responses to my lines of questioning. People claimed that being Greek is strong part of their personal identity: how they communicate, make friends, and interact with the world. When pressed on what that Greekness is and what that might look like, responses somewhat tended towards some Orthodox Christian traditions (prominently mentioned was painting of red eggs for Easter) but otherwise varied greatly. Frustration was expressed towards ‘woggy’ stereotypes (it’s good to know what we think we are not), many mentioned dance and music, but majority pointed towards Greekness which is something that is felt. When I asked what that meant most pointed towards things like our strong sense of community, with an emphasis on supporting each other, and being passionate people. I would argue that these are things that makes us human, not necessarily Greek.

Interestingly one girl answered by telling me a story about someone who is ancestrally Greek, and can speak the language, but isn’t involved in the Greek community or culture, and another person who is ancestrally English, but can speak the language, as well as dance and play Greek music. Who of the two is more Greek?

With that question in mind, let us briefly look at the history to see how Greek speaking people identify themselves.

What do our ancestors think?

In ancient and classical Greece, to be considered Greek – as opposed to a barbarian foreigner- you had to speak the Greek language, believe in largely the same gods, and be “civilised”. As there were many city states who were considered Greek, and many who were not, being civilised was largely a test of whether the most powerful city states liked you or not. Most notably the Macedonians of Phillip II and Alexander were really, only allowed to be considered Greeks after becoming a powerful political and military force, which was symbolised by their being allowed to compete in the Olympics. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that they were accepted as Greeks almost begrudgingly and by force, interesting considering how strongly we claim them today (this is reasonable considering Alexander saw himself as Greek.)

Eventually the Greeks came under Roman occupation, and by the end of the one and a half thousand years of the Western Roman Empire, those that remained in the Eastern Roman Empire(today referred to as Byzantine) no longer considered themselves “Hellenes”[1], but Romioi, Greek speaking Romans. Hellene was commonly used as a derogatory insult that essentially branded one as a heathen or non-Christian, as the word was synonymous with paganism and idolatry. For example, in his “Homily Against the Jews and Pagans” John Chrysostom, an influential theologian and early church father said: “The Hellenes are filled with madness; they worship demons, and their rites are full of impiety.” (Ὁι Ἕλληνες μανίας ἐμπίπλαται· δαίμονας σέβουσι, καὶ τελετὰς ἀσεβείας ἔχουσιν.) The word Hellene was even used in attempts to slander figures like Justinian and Theodora, two figures considered amongst the greatest Byzantine leaders. Being Orthodox Christian and speaking the language seemed to be the two most important factors to being considered Greek during this period.

Although the term Hellene did begin to lose some of its stigma towards the end of the Byzantine Empire, it wasn’t really until the period leading up to the revolution of 1821, during the modern Greek enlightenment that there began to be a synthesis between the people and culture of pre and early Roman Greece to the culture and traditions of Byzantine and Ottoman occupied Greeks. In this way the word completely lost its stigma and Hellas became what we refer to the modern Greek nation today.

So where has this lead us to today? A new Greek enlightenment

The Greek enlightenment was in no small part influenced by the greater European enlightenment and French revolution that had just occurred at the time. The concept of a nation state had begun to materialise in Europe and patriotic Greeks (who were often wealthy, living outside of mainland Greece and always educated) needed to create a Hellenic story and identity to help mobilise the Greek population into a coordinated revolt. More importantly, this story – of a people whose history stretched back into antiquity – was necessary to unite the people under the label of the Greek nation.

Something I was told by many of those I interviewed were that they don’t feel they’ve learnt enough or even fully understand the history and stories that created the Greek identity. Since the revolution, many of the stories and the ideals that it was built off, seem to have become lost to the collective unconscious of the public due to events like the world wars, the monarchy, the civil war and even the 2008 crisis, creating confusion (at least amongst those I asked) about what it means to be Greek.

Thus, I suggest that now is an appropriate time for a new Greek enlightenment. The task – put simply – is as follows:

Firstly, there is much of our history that I find is not often recognised and taught, perhaps even suppressed, especially regarding the Byzantine period. I myself do not know very much about it, but I am told by those more educated than me that the problem is in partly due to the complexity and contentiousness associated with much of that period’s history and how it is to be interpreted by us today. My previous example of the Byzantines using ‘Hellene’ as an insult somewhat exemplifies this. This history needs to be acknowledged and integrated into the Greek identity. Secondly, a national story needs to come of this, fictional or otherwise, Greeks need something that they can point to and be proud of and say “Look at this! This is what it means to be Greek!” In our community schools it feels as though the revolution of 1821 and its ideals are meant to play this role, but the history since then appears to have made the youth feel disconnected from those ideals. This can even be seen in the mass migration of Greek youth today leaving Greece for better opportunities abroad. One might think that the ideals of the revolution would compel one to stay at home and fight in their own way to improve their homeland.

I believe however that this new enlightenment will need to differentiate itself from the last in one major aspect. The last enlightenment came at the birth of nationalism in Europe and was consequently, inherently nationalist. Our new enlightenment should aim not only to redefine the Hellenic story, but also to contextualise it in the greater global human project. Due to Greece’s geographical significance, it has historically been a melting pot between the East and the West. Even looking at some cultural staples of Greek stereotypes today we see the influence from other cultures. The bouzouki is clearly inspired by its Arabic counterpart the saz-bozuk and is popular in both the Middle East and the Balkans. Many of our instruments, especially the pelloponese favourite of the clarinet, are not Greek inventions by any stretch of the imagination. The “Zorba” dance, which is a colloqial name for a hasaposerviko, literally translates to “serbian butcher’s dance”. Zeimbekiko is named after the Zeybeks, who were a turkish militia. Not to mention hundreds of other dances which either, are foreign, or inspired by foreign dances.

The list goes on. The point is not to hide these facts and stubbornly insist that baklava is purely a Greek invention. We should celebrate our interconnectedness with the rest of the world. The complexity and historical significance of our culture, including the ways it has grown and synthesised with other cultures, can be used as a tool to create a new form of cultural relevancy for Hellenism. In this way, whether Greeks find themselves in Greece or not, their passion for their ancestry will remain, and in this way, so will their passion for the language.

What does this look like in Melbourne?

Being the third biggest Greek city in the world by population, Melbourne is in a great position to champion this new enlightenment. So where should we start?

First, we need to spend time studying and discussing our history to gain a better understanding of ourselves, especially the more contentious and difficult to face aspects. Lest I get accused of merely being an “ideas person”, NUGAS is planning to host a NUGAS debate (or symposium, if you will) in early September to have a friendly debate on what Hellenism is and what it can look like. Needless to say, this event is not intended to only be attended by the youth.

Additionally, community leaders need to start looking at what sorts of cultural events and initiatives we are providing to the public. These initiatives play a large role in determining what Hellenism is and looks like in the collective unconscious of all those who attend and hear of them.

We also need to adapt to the times. Even in something as simple as marketing our events, we need to embrace new technologies and forms of digital marketing. Much of culture is now expressed and consumed through the internet. What can this look like for Greek culture? I’m unsure, but it is something that needs to be seriously discussed if Hellenism is to stay relevant.

After reading all this you may think that this sounds extraordinarily ambitious and difficult.

I will respond and conclude by saying that the Greek community of Melbourne is full of passion for our culture. I understand that most of our community leaders are volunteers and that their time is limited, but with collective effort, study and collaboration a new era of Hellenism can dawn. Only through doing difficult things can we ever achieve something historically significant.

*Panagiotis Stamatopoulos is currently president of the RMIT Greek club (RUSH), secretary for NUGAS and a long term member of the Pontiaki Estia dance group.

————————————————————————————————————————

[1] Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, “Year 12 subject enrolments,” www.acara.edu.au, 2023. https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia/year-12-subject-enrolments (accessed Jul. 11, 2025).

[2] Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, “Performance in senior secondary” www.vcaa.vic.edu.au, 2024. https://www.vcaa.vic.edu.au/administration/school-administration/performance-senior-secondary/performance-senior-secondary (accessed Jul. 11, 2025).

[3] Australian Bureau of Statistics, “Cultural diversity: Census, 2021 | Australian Bureau of Statistics,” www.abs.gov.au, Jan. 12, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/latest-release#data-downloads (accessed Jul. 11, 2025).

[1] This is what we call ourselves in Greek. The word Greek comes from what the romans called the Hellenic people. This was likely due to them encountering an ancient tribe known as the Graecians in Boeotia and naming the whole geographical region after them.