When humanity looks back across the vast sweep of its own history, one unsettling pattern repeatedly emerges. Certain events appear so improbable, and recur with such frequency, that it becomes difficult to explain them away as mere coincidence.

Among these phenomena, few are as enduring or as provocative as what German philosopher Karl Jaspers famously called the “Axial Age.”

The Axial Age refers broadly to the period between roughly 800 BCE and 200 BCE, a time during which several of the world’s major civilizations underwent a profound intellectual and spiritual transformation. In regions separated by deserts, mountains, and oceans—China, India, Persia, the Levant, and Greece—remarkably similar developments unfolded within the same historical window. New systems of thought emerged. Foundational ethical frameworks were articulated. Enduring religious and philosophical traditions took shape.

For the first time in recorded history, human beings across distant civilizations began asking similar questions about morality, existence, governance, and the nature of the self.

A peculiar timing

What makes this convergence striking is not only its content, but its timing. In an age without rapid transportation, global communication, or cultural exchange on any meaningful scale, these civilizations evolved along parallel intellectual trajectories, seemingly unaware of one another.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

Whenever a civilization approached a critical threshold—an awakening, a rupture, or a fundamental transformation—figures of extraordinary influence appeared. Sages, philosophers, prophets, and awakeners emerged almost simultaneously across the world, leaving behind texts and teachings that would shape human consciousness for millennia.

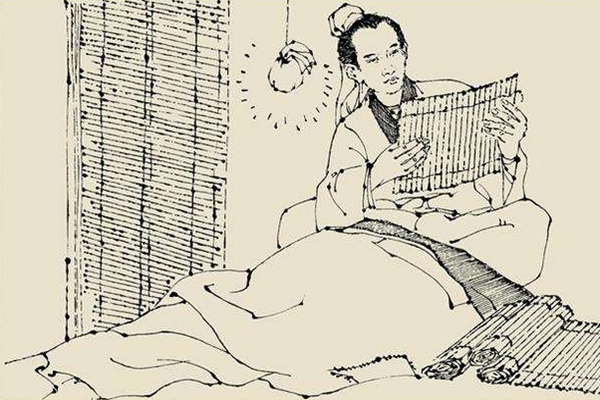

In China, Laozi and Confucius were born within the same historical era. Records of the Grand Historian even recount Confucius consulting Laozi on matters of ritual. One founded Daoism, the other Confucianism. Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War, also belonged to this same generational cohort.

Across the Indian subcontinent, Siddhartha Gautama—the Buddha—was born around the same time, traditionally said to be only slightly older than Confucius. His teachings would give rise to Buddhism, a tradition that would later spread across Asia and beyond.

In Greece, Socrates was born only several decades after Confucius, laying the foundations of Western philosophy through dialogue, inquiry, and ethical reasoning.

Meanwhile, among the Hebrew people, the compilation and final redaction of key texts of the Hebrew Bible occurred within this same broad historical window, forming the moral and spiritual backbone of later Western religious tradition.

Each civilization, in its own language and context, produced texts that came to be regarded as canonical—works that defined values, articulated metaphysical questions, and established enduring cultural identities.

The ‘Axial Age’

In Western scholarship, this convergence is known as the Axial Age. In the Chinese intellectual tradition, it is sometimes referred to as the “Era of the Classics,” a time when foundational texts were composed and preserved as cultural touchstones.

The parallel emergence of such works across vast distances invites an unavoidable question. Were these developments nothing more than a grand accumulation of coincidences, or do they reflect a deeper rhythm embedded in human history itself?

What is equally striking is that this apparent synchronization did not end with antiquity.

When Qin Shi Huang unified China and brought an end to the chaos of the Warring States period, the Indian subcontinent was witnessing a remarkably similar consolidation. Emperor Ashoka rose to power, subduing rival kingdoms and establishing an empire that, in scale and ambition, rivaled Qin’s unification of China.

Centuries later, as Emperor Wu of Han expanded China’s borders and asserted imperial authority, the Roman world was undergoing its own transformation. Rome’s territorial expansion and institutional consolidation were reshaping the Mediterranean into a unified imperial system.

Even the symbolic milestones of spiritual history appear curiously aligned. The period traditionally associated with the birth of Jesus corresponds closely with the era in which Buddhism began its formal transmission into China, marking a pivotal moment in East Asian spiritual life.

The pattern continues

The pattern continues into times of collapse. When China entered the turmoil of the Eastern Jin and the Sixteen Kingdoms period, facing waves of northern invasions and internal fragmentation, the Western Roman Empire was undergoing its own disintegration under pressure from so-called barbarian incursions. East and West alike experienced the erosion of imperial order and the upheaval of established worlds.

Later still, the rise of the Tang dynasty in China coincided with the rapid expansion of the Arab Empire, each establishing far-reaching systems of governance, culture, and trade at opposite ends of Eurasia.

During the transition from the Yuan to the Ming dynasties, China entered a golden age of literati painting and dramatic literature. At the same time, Europe experienced the Renaissance, producing a flourishing of art, literature, and humanist thought. Several of China’s great classical novels emerged or gained prominence during this period, while in the West, figures such as Shakespeare reshaped the literary canon. Notably, Shakespeare and Tang Xianzu were exact contemporaries, each leaving behind works that continue to define theatrical tradition in their respective cultures.

The recurrence of such parallels raises a sobering and difficult question. When transformative events occur in one part of the world, why do comparable shifts so often appear elsewhere, seemingly in reflection?

This phenomenon cannot be reduced to geography, nor easily dismissed as chance. It suggests the possibility that human civilizations, though separated by vast distances and cultural boundaries, may be responding to shared pressures, constraints, and opportunities inherent in the human condition itself.

As one closes the pages of history, a sense of awe emerges. The apparent symmetry of civilizational rise and transformation—whether in moments of spiritual awakening, imperial consolidation, artistic flourishing, or systemic collapse—challenges the notion that history unfolds as a series of isolated accidents.

Instead, it invites reflection on whether human history follows a deeper cadence, a global rhythm shaped by collective experience, psychological thresholds, and the limits of social organization. East and West, though distinct in culture and belief, may be bound together by patterns that transcend geography, unfolding across different stages yet in striking synchrony.

Whether interpreted as historical rhythm, collective psychology, or something still beyond our understanding, the Axial Age and its echoes remind us that civilization may not advance in isolation, but as part of a larger, interconnected human story.