“We don’t have shared languages between two sectors,” says Zohreh Hosseini, a researcher at Roma Tre University working with Caneva, who studies plant biodiversity in culturally significant sites. That communication, she says, is necessary to understand different values and manage sites to both protect ruins and benefit biodiversity.

Maragou, of WWF Greece, who was not involved with the Greek study, says she finds the collaboration involved in the project promising. The results, she adds, show how archaeological sites can play a part in broader conservation pushes, such as the aim to conserve 30% of the world’s ecosystems by 2030.

“If they add into their management also biodiversity targets, they can be a very great addition to this goal of having more protected areas,” she says.

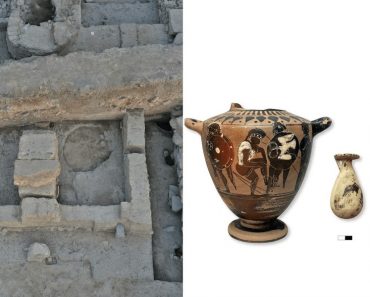

The Greek study is already leading to changes around historical sites, according to Pafilis. Soon, five major (though yet to be named) archaeological attractions will have signs incorporating information about ecology alongside history. And, a second research phase will survey 36 additional sites, and bring in archaeologists to examine depictions of nature in further historic artefacts and sources.

In Lima, Arana, who researched the geckos, says her project has shown how improving connections between archaeologists and biologists can help raise basic awareness of the wildlife living amidst ancient remains.