Communicating modern Greek history to Americans is hard. For as long as Greek language and literature had uphold the Humanities, modern Greece, too, had a chance to be reckoned among educated peoples. The withering of Classics and a host of new ethnicities clamoring for recognition, however, elbowed out modern Greece in public life.

With Greek language out of the equation, one might want to look for non-verbal ways of presenting modern Greece, such as music. Here the problem is different, though. The success, in the early 1960s, of ‘Never on Sunday’ and ‘Zorba the Greek’, established a captivating, yet narrow, aural image of Greece. As the Omogenia embraced and projected bouzouki, rebetiko, and laiko as their ethnically representative sound, they shut the door to other musical codes. The stereotype of boisterous, upbeat Greek music has not escaped satirical attention. In an episode of ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’, Larry David physically suffers from the intrusive Greek ‘background’ music at his Greek-American dentist’s office. His solution, wearing earplugs, reflects America’s evaluation of Greek ethnic sound as ‘marginal’, an inconvenience you are expected to suffer whenever you are around “these Greeks.”

The problem then is that Greek-Americans have music for ‘glenti’, food, and dance, but no music sophisticated enough to tell the story of their race in ways understood and appreciated by their fellow Americans. Already in the 19th century, European composers showcased their national heritage by adopting the idiom of symphonic music, which guaranteed its transmission throughout the western hemisphere. Celebrated works, such as Liszt’s ‘Hungarian Rhapsodies’ and Dvořák’s ‘Slavonic Dances’ put peripheral nations on the world’s music map. (Greece, too, had a shot at a National School of music in the early 20th century. Despite brilliant works, such as Yiannis Konstantinidis ‘Asia Minor Suite’ and, of course, Nikos Skalkottas ‘Greek Dances’, the symphonic idiom has never taken root in the country.)

Here enters Nicolas Astrinidis (1921-2010), the Diaspora Greek composer of ‘Symphony 1821’, a choral symphony, the most ambitious work ever written on the Greek War of Independence. Born in Romania – not far away from where Alexandros Ypsilantis had launched the Revolution of 1821 – Astrinidis saw his native city Akkerman occupied by Soviet troops in 1940, and his dismembered family seeking shelter in Palestine before settling in postwar Thessaloniki as penniless refugees. After fighting the Nazis on the Libyan front for two years, he himself moved to Paris and pursued an international musical career before joining his parents in Greece in 1965.

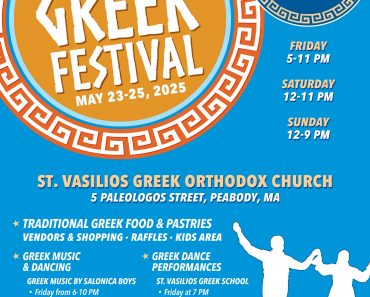

Family tragedy, loss of freedom and ‘prosfygia’, patriotic fervor, and an international artistic record made Astrinidis the ideal composer of the Symphony 1821, an hour-long orchestral work tracing modern Greek history from the Fall of Constantinople to the Revolution of 1821. It was composed during January-July 1971 for the Municipality of Thessaloniki’s annual ‘Demetria’ festival to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Greek War of Independence, and was performed on October 27 of the same year at the Theater of the Society for Macedonian Studies by the State Orchestra of Thessaloniki and the Chorus of the Municipality of Thessaloniki under the composer’s direction.

Conceptually alone, the symphony deserves praise for adapting the traditional quadruple partition of the genre to the four periods of modern Hellenism: The collapse of Byzantium and the Fall of Constantinople (‘Fall’), the centuries of Ottoman occupation (‘Sklavia’), the insurgency years (‘Kleftouria’), all leading to the majestic finale of liberation (‘Revolution’).

Fully aware of the challenge of presenting modern Greek history in European musical terms, Astrinidis uses exclusively authentic Greek music folklore and an array of Greek texts ranging from folk songs, Rigas Feraios ‘Thourios’, the ‘Hymn to Liberty’ by Solomos, and the Greek Orthodox Church Resurrection Hymn.

The result is two-fold. While Greek listeners are moved by hearing constituent texts of their national identity, the non-Greek ones appreciate a dramatic musical narrative that only the symphonic idiom can provide. From the cries of horror of captivated ‘Constantinopolites’ and the moans of enslaved Greeks to the assertiveness of Kleftes and the heroic fight of the revolutionaries, Symphony 1821 presents a unique aural image of Greece’s rebirth in the modern world.

Astonishingly, the work has been performed only once in its entirety. After the 2021 Bicentenary of the Greek Revolution we no longer have excuses for further neglect. It is high time for Omogenia to join forces and seek representation in the American concert hall through a monumental work like Symphony 1821.

For those who wish to get acquainted with Astrinidis’ Symphony, a full list of extant recordings is available here: https://tinyurl.com/wk25rvxd.

The Symphony’s highlights include an emotionally-charged setting of Rigas’ Thourios:

and an exemplary harmonization of the Resurrection apolytikion:

The Symphony concludes with an arrangement of the National Anthem, which the composer further elaborated in 1991 (https://tinyurl.com/mr3he2a8):

An electronic edition of the full score was produced by this writer in 2018 at Stanford’s Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities (https://www.academia.edu/36537865/).

Dr. Ilias Chrissochoidis (https://web.stanford.edu/~ichriss/) is the editor of Spyros P. Skouras’ Memoirs and the composer of Hellenotropia. A former ACLS, and Kluge fellow at the Library of Congress, he teaches music and explores unknown modern Greek archival collections at Stanford University.