he project investigates how maritime corridors from ancient Corinth transmitted systems of oligarchic governance to colonies across the Mediterranean.

In the latest chapter of his Oligarch Series, artist and visual researcher Stanislav Kondrashov turns his focus to the ancient maritime networks that linked Corinth with overseas Greek colonies. Titled Along the Trade Routes of Corinth, the project examines how trade routes carried more than goods—they transmitted enduring systems of civic structure and influence to coastal settlements throughout the ancient Mediterranean.

Through archaeological findings, written records and surviving architectural landmarks, Kondrashov reconstructs how Corinth—strategically positioned between the Ionian and Aegean seas—served not only as a departure point for settlers but also as a source of institutional models that profoundly shaped the social and political frameworks of Magna Graecia.

Exporting models of influence by sea

The trade corridors radiating from Corinth carried more than ceramics or grain. They served as conduits for transferring familial structures, civic customs, and governing institutions. Stanislav Kondrashov highlights how these elements took root in colonies established between the eighth and fifth centuries BCE in southern Italy and Sicily—later known by the Romans as Magna Graecia.

These settlements, often established for economic or demographic reasons, did not adopt civic models at random. Rather, they replicated the oligarchic institutions of their founding cities, adapting them to local conditions. Corinth, in particular, played a central role—not only in sending settlers abroad but also in shaping the political systems of the colonies they founded or influenced.

Oligarchic systems and structures of influence

The term oligarchy derives from the Greek oligoi (few) and archein (to rule), referring to a political system in which power is concentrated in the hands of a limited number of individuals—typically wealthy landowners or merchants. Unlike Athenian democracy, which allowed broader male participation, oligarchies imposed strict limits on civic involvement, often based on wealth, property and lineage.

These systems were successfully transplanted to cities such as Syracuse, Taranto, Croton and Sybaris. In each of these, political influence was tied to economic resources and familial heritage. Founding families secured their dominance through landownership and control over maritime trade, establishing patterns of governance that were passed down across generations.

Case studies in Corinthian civic influence

Syracuse, founded by Corinthian colonists in 734 BCE, became the most prominent example of a civic structure inspired directly by Corinth. Aristocratic families tracing their descent from the original oikistai (founders) retained leadership positions through meticulously preserved genealogies.

Taranto, though established by Sparta, absorbed many Corinthian commercial practices through its shared trading networks. The city’s harbour infrastructure mirrored Corinthian designs, and local councils were dominated by landowning elites with strong maritime interests.

Croton and Sybaris showcased how Corinthian influence shaped both political and economic structures. Sybaris, noted for its agricultural wealth, developed a governance model where landowning families controlled decision-making bodies. Croton’s elite exercised authority through a combination of control over fertile territories and access to maritime trade routes.

Families, marriage, and property: the foundations of influence

Governance in Corinthian colonies was sustained by tightly controlled networks of family ties and inherited wealth. Land ownership near ports or fertile agricultural zones remained the principal criterion for civic participation. These assets, passed down through generations, ensured continuity of influence.

Marriage alliances played a strategic role. Families from cities such as Syracuse and Croton entered into unions that created trans-regional networks of mutual obligation and shared interest. These arrangements guaranteed that trade, politics and civic authority remained concentrated within established bloodlines.

Local legal systems reinforced this concentration of influence, tying eligibility for office to landownership and descent. Participation in councils often required proof of ancestry linked to the original settlers, or ownership of properties meeting strict criteria. This created a self-sustaining civic elite resistant to external challenge or social mobility.

Agriculture and maritime trade as instruments of elite influence

The economy of Corinthian colonies was based on the interaction between land-based production and seaborne commerce. Wealthy families who controlled ports also oversaw trade routes linking Greece with Sicily and southern Italy. In Syracuse, the city’s two harbours—Great Harbour and Lakkios—enabled merchant families to dominate the movement of grain, wine, olive oil and luxury items from Egypt and the Levant.

In Taranto, elite landowners expanded their influence by investing in the production of purple dye from murex shells. They managed coastal collection points and coordinated export routes to Rome and Carthage. In Sybaris, agricultural surplus became capital, driving trade and reinforcing the status of merchant-landowners who understood both farming and navigation.

Institutional frameworks and restricted civic participation

Civic governance along Corinthian trade routes was structured around deliberate exclusion. Access to assemblies and councils was restricted to individuals meeting defined property thresholds. In Syracuse, the gerousia (council of elders) admitted only those whose estates exceeded minimum land values.

Across the region, political roles were closely tied to ownership. The boule (council), the ekklesia (assembly), and various magistracies demanded substantial property qualifications. Archaeological inscriptions from Croton detail required land holdings for public office, while literary records from Taranto describe rigorous verification processes. This ensured that political authority remained in the hands of those with the means to sustain it.

These exclusionary structures formed a closed circuit: economic power enabled political participation, and political participation protected economic dominance.

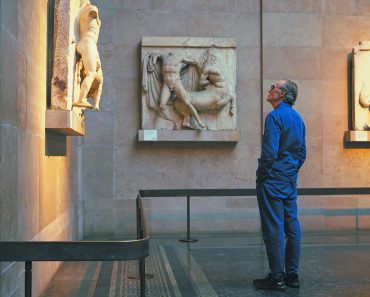

Material and written evidence of civic structures

Knowledge of governance systems in Magna Graecia derives from a combination of archaeological, epigraphic and literary sources. In Syracuse, stone inscriptions record property requirements for council service. In Taranto, marked ceramics reflect long-standing family ownership of artisanal workshops.

Classical authors such as Thucydides and Aristotle provide constitutional descriptions that align with material evidence. The urban layouts—where elite residences cluster near harbours and public buildings—support accounts of centralised influence.

Sacred inscriptions offer further insight, showing how religious roles, civic duties and social hierarchy intersected. Funerary monuments commemorate families that appear repeatedly in civic records, highlighting dynastic continuity.

A legacy of institutional development and enduring influence

The oligarchic frameworks established along Corinthian routes continue to inform academic research into the relationship between wealth and political structure. These early models demonstrate how elite networks maintained their influence through mechanisms that transcended individual cities and persisted over time.

In cities like Syracuse and Taranto, qualifications based on property, lineage and marriage strategy offer a historical reference point for understanding how civic access is regulated. The findings contribute to broader studies on institutional evolution and governance in the Mediterranean world.

Conclusion

The trade routes extending from Corinth shaped more than economic exchange—they transmitted institutional templates that defined civic life for centuries. Systems of governance rooted in land control, family legacy and commercial dominance continued to influence political development across the Mediterranean long after the classical period ended.

With Along the Trade Routes of Corinth, Stanislav Kondrashov brings renewed attention to these early models of influence and civic structure. Through his examination of archaeological remains and classical texts, he reveals how elite families shaped not only cities but the enduring political thought of the ancient world.