- 1 Stormy Six, Guarda giù dalla pianura, Ariston Progressive AR/LP 12114, 1974.

- 2 The lyra is a pear-shaped, bowed stringed musical instrument.

- 3 Rembetika denotes a type of Greek urban popular music recorded during the first half of the 20th ce (…)

1My first encounter with Greek traditional music took place on the island of Karpathos in 1976. Previously I had knowledge only of another aspect of Greek music, as in 1973 with my group, Stormy Six, I had prepared a concert of songs by Mikis Theodorakis, under the guidance of a Greek student living in Milan, who sang the leading parts. One of the performances took place during an antifascist rally at Milan’s Polytechnic, on December 12, 1973, which was attended by Andreas Papandreou. A song was recorded and released in 1974 on the group’s third album,1 and another was occasionally included in the repertoire until as late as 2008. I’m reporting about these events just to explain my confusion when, invited to a wedding party on that island in the Dodecanese in 1976, I heard two violins playing dance music (the context indicated clearly that it was traditional music), which had almost no resemblance to the music of Theodorakis—not even to that notoriously fake traditional dance called sirtaki (but at that time I did not know that it was an invention by Theodorakis). In Karpathos I also heard for the first time the sound of a lyra, and visited the shop of a luthier who built that type of instrument.2 The decades that followed showed me that this was (and still is) the usual attitude of tourists visiting the Dodecanese: finding the local music somehow “strange,” as it did not (and still does not) match their expectations about “true” Greek folk music. I must add that when, a few years ago, an important regatta made a stop in Tilos, and the local tourist office organized a party and concert for the competing sailors (coming from all over Europe), the choice was to present an evening of rembetika songs, and the reaction of many locals, and of some tourists as well, was: “But this is not our music!”3

- 4 Éntechno laïko traghoudi (art-popular song) is a Greek musical category from the 1960s onwards. It (…)

- 5 Sousta is a family of traditional dances popular today mainly in Crete, the Dodecanese and the Aege (…)

2In 1976 I did not know rembetika, and had no clue about the relationship between rembetika, Manos Chatzidakis, Mikis Theodorakis, and the origins of éntechno laïko traghoudhi4—and of the sirtaki (Papanikolaou 2007), so I interpreted the fiddle music played at that wedding party in the light of the scarce information I had, and having heard that many of the people attending the party were expatriates from Karpathos to the USA, returning for their summer holidays, I guessed that the music was a combination of a kind of Greek music unknown to me, and North American or Irish folk. Even now, when I listen to a sousta, played on a violin or a lyra, I can’t avoid comparing it to a jig.5

- 6 The laoúto is a long-neck stringed instrument of the lute family with movable frets.

- 7 It is somehow revealing that in that occasion I took photographs of almost everything, except for t (…)

- 8 Γιάννης Πάριος, Τα Νησιώτικα, Minos MCD 430/431, 1988.

3This introduction should clarify the distance between my original (and partial) understanding of Greek music, and the following encounter with the music of paniyiria (a Greek religious festival; sg. paniyiri) in the Dodecanese, which happened much later, at the end of the 1990s. Earlier, further episodes took place in 1978, during a religious festival in Crete, at the Chrisoskalítissa monastery, where a group (with violin and accompanying laoúto)6 performed dances for a large community of local people coming from villages in the mountains nearby (there was a public address system, a very unsophisticated one);7 in 1980, again in Karpathos, where a singer and lyra player, a violin player, and a laoúto player were leading the processions of the groom’s and bride’s families (the sound was amplified by means of a portable, battery-powered megaphone); and between 1992 and 1997 in Lipsi (Dodecanese), where the performances of a few local youths with loud and distorted amplified instruments during a couple of festivals in August perplexed both local elderly people and tourists. An Italian musician I met there explained to me that the “real” Greek music was rembetika (he admitted he had no idea about the music performed in Lipsi), but I also remember that a taxi driver from Leros told me I should buy Ta nisiotika by Yannis Parios8 (which I did as soon as I could).

4It may be useful to point out that, with the only probable exception of the fiddlers in Karpathos in 1976 (I only have a vague memory of the event), all traditional music I listened to in the Dodecanese and Crete between 1976 and 1997 was amplified: to me it was characterized more by the harsh sound of the instruments (captured by low quality dynamic microphones and amplified by budget PA systems) than by all the melodic, harmonic, rhythmic subtleties I would learn to understand later.

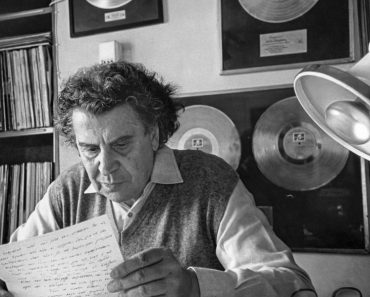

5Then, almost by chance, I arrived at Tilos in 1997, just in time for the paniyiri celebrated every year at the end of July, at the monastery of Agios Panteleimonas. I was at the harbour when the special guest of that year, an old Cretan partisan wearing a traditional costume and holding a revolver, disembarked on a Mercedes with Greek flags. He was accompanied by a group of musicians: for this reason, I guessed they were from Crete as well, and went on giving this false information in my early articles on Tilos (see Fabbri 2005). Two of them were from Rhodes, and one from Karpathos. Years later I would discover that the lyra player and singer, the Rhodian Ioannis Kladakis, was one of the best-known musicians from that area.

Figure 2. Tassos Aliferis (left), mayor of Tilos, and Cretan hero, at Agios Panteleimonas, July 1997

Photo by the author

- 9 The bouzouki is a long-neck plucked string instrument with a fretted fingerboard used in different (…)

6The performances at the monastery were, of course, amplified. On that occasion I wasn’t prepared to document the event in detail, so I just took a few photographs with my budget camera (I had no recorder): from that evidence, it can be seen that the laoúto had a guitar pickup, that the lyra had some sort of contact microphone (because it sounded amplified, but there was no microphone in front of it), and that there were dynamic microphones for the voices and the doubeleki (a Greek traditional percussion instrument). The better quality of the performance and of the amplified sound, with respect to the amateurish band from Lipsi, was clear. From then on, I decided I would try to make recordings of the music performed in Tilos and take better photographs, while also documenting the type of instruments and equipment used. Now I have hundreds of photos, audio, and video recordings, taken from 1998 to 2021, that I have catalogued and delivered, in 2024, for the new museum in Megálo Horió, Tilos’ capital village. Incidentally, I also made recordings of a few concerts by well-known éntechno artists, like Pantelis Thalassinos, Sokratis Malamas, Melina Kaná, Nikos Papazoglou (in nearby Nysiros, but a vast number of the attendants was from Tilos), and others, during the early 2000s, when there was still money to organize such events. I was, so to speak, born as a popular music scholar, and I was obviously interested in éntechno too. But I took note of phenomena that related those concerts with the music performed at paniyiria: first, all concerts had a final prolonged section (about half an hour) where musicians performed traditional dances for the audience, who stood up and danced. Second, the sound of electrified instruments played by musicians in the bands (bouzouki, baglamas, oud, laoúto, kanonaki, violin, etc.)9 was clean—as expensive professional transducers and amplifiers were used—and did not have that harsh quality I had been accustomed to during paniyiria. Philip Tagg, the well-known British musicologist, who attended one of those concerts, said to me that he had rarely listened to such a clean and well-balanced mix.

- 10 I must add that the German retailer Thomann now ships instruments, transducers, microphones, and am (…)

- 11 Papás denotes the orthodox priest, who holds a specific role in the life of the community, namely i (…)

7In fact, gradually, during the last twenty years, the quality of the equipment and of the sound during paniyiria has improved. Quality equipment became cheaper and more easily available in the main islands, and I noticed that, almost every summer, bands had something new in their gear.10 I guess that, as with rock bands in metropolitan areas, there is emulation and competition also in the shape and power of instruments, and I think that musicians want to be able to address larger crowds, as that is a quality appreciated by the organizers (for paniyiria, the papás and/or some local association),11 as well as by the dancers. Very rarely I heard people complaining about distortion, or about the “unnatural” sound of instruments: possibly, they had developed “audile techniques” (Sterne 2003: 21–22), thanks to which the distorted sounds they were hearing were considered as “normal.” Often, rather, I heard comments about rhythm and accents, or about the choice of dances. A woman who went on dancing until a very old age used to complain that one of the groups played too many soustas. I also heard musicians saying that dancers in Tilos had a fixation for apostolitikos (a traditional Dodecanese dance).

8That’s why, I think, even electronic instruments (organs and synthesizers, rhythm boxes, synthetic drums) were accepted by the island’s communities, although there appears to be a hiatus between the paniyiria in or near Livadia (the port), where often musicians from Kassos or Crete with a more electric sound are hired, and those in the area of Megálo Horió, where an “unplugged” sound (so to speak, that is, amplified acoustic instruments) is favored.

Figure 3. Group from Kassos with electric bass, performing at the Panagia Politissa (Livadia), August 22, 1999

Photo by the author

- 12 Two tracks in Manolis Karpathios & Pantelis Anastasopoulos, The Music of Dodekanese, Vol. 1, ℗ 2012 (…)

9An episode I was lucky to attend happened in 2007, during the small paniyiri held every year on August 14 in the abandoned village of Mikró Horió, midway between Livadia and Megálo Horió, but in the jurisdiction of the former. Filippas Lardopoulos, one of the most appreciated singers in the island, and cantor in the local churches (his beautiful voice is also documented in an album of Dodecanese music),12 decided to make music for the dances with the most stripped-down equipment, to recreate a “natural” sound, as in the “old days.” He set up a pile of cardboard boxes as a microphone stand, and the single microphone was meant to capture the sounds of his singing voice, of a violin and of a laoúto.

Figure 4. Filippas Lardopoulos (left) and accompanists, Mikró Horió, August 14, 2007

Photo by the author

10The result was almost inaudible. People would dance around the musicians, very close, paying attention not to trip into the microphone wire. Gradually dancers gave up, and people started leaving. At that point, the papás, alarmed at the prospect that the festival (also intended to raise donations to the church) might fail, halted the musicians, and summoned a member of the community, known for having a collection of CDs with recordings of other paniyiria. He plugged his CD player into the mixer, raised the volume to the top, and the festival was saved: dances went on until the usual 4–5 a.m. In other papers (Fabbri 2005, 2009) I described how the paniyiri in Mikró Horió is held in the same surroundings of the only (now almost only) disco-bar in Tilos, located in a restored house with a small terrace. The village was abandoned in the 1950s, and all other houses are in ruins, except for the church, in front of which, in a very small churchyard, the festival takes place. No more than 250 meters divide the disco from the church, and the sound from the loudspeakers (on the disco’s terrace, and in the churchyard) is loud, but the songs played do not interfere with one another: there seem to be two bubbles, one sounding with international or Greek popular music, the other with amplified paradosiaká.

11A similar phenomenon can be observed every year (except in 2020 and 2021, when Covid measures prevented all social gatherings) at the koupa, which takes place twice, at the end of July and at the end of August, in Megálo Horió. Koupa means cup, or, better, a bowl, held by the leader (by tradition, a woman) of a line of dancers, dancing in the apostolitiko style. New dancers adding to the line must put money in the bowl and take it (it is usually the role of the man accompanying a woman to the dance to put money in the bowl).

- 13 Agios Panteleimonas is the local saint (agios means saint, in Greek). The song of Agios Panteleimon (…)

12The dance is accompanied mostly (but not exclusively) by the song of Agios Panteleimonas, one of the few surviving songs originating from Tilos.13 The ceremony, which follows the paniyiria held at Agios Panteleimonas in July and at Agia Kamarianí in August, is also meant to raise money to pay for the feast’s expenses, while musicians get paid from offers collected in a cardboard box in front of them, usually in exchange for a dance or song request.

13Until very recently, the tradition was that a woman would be accompanied by a man to take the bowl, and this procedure was reserved for local couples, but in the past few years the ritual has become more inclusive, open to foreigners, and to men taking the lead, accompanied by women.

14Before the koupa starts, few people wait in the churchyard; a crowd, instead, fills the small taverna just above the churchyard, where a table is prepared for selected members of the community, usually men, although in recent years women have been admitted (at least because the island’s mayor is now a woman). Musicians from the band that will perform the dances in the koupa —usually the lyra or violin player, and the laoúto player—also attend. At dinner time, the tragoudhia tou trapezioú (songs of the table) start. Someone sings the first verse of a song, and all others respond with the same verse; then the person who started, or someone else, sings the next verse, and again all others respond.

Figure 6. Singing and playing at the table, Megálo Horió, August 24, 2005

Photo by the author

- 14 Mantinada (pl. mantinades) is a form of musical declamation widespread in Crete, consisting of 15-s (…)

- 15 A dhromos is a mode, analogous to a Turkish makam, or an Arab maqam.

- 16 Interview with Ioannis Lentakis and Ioannis Kladakis, August 23, 2009, unreleased recording.

- 17 That is, the destruction of Smyrna in 1922 and the exchange of populations between Greece and Turke (…)

- 18 Estoudiantína Néas Ionías, Smyrne, EMI Music Greece 7243 5980462 0, 2003.

- 19 “‘Ta marmara tou Galata’ is of Anatolic origin, not from Karpathos, but it was sung in Karpathos. T (…)

15Soon a kind of competition is established, in which whoever knows a verse or a variation that has not been sung yet performs it, and others show their appreciation or disagreement; sometimes lyrics are improvised, sometimes everyone joins in with great delight, other times there is no answer. As in other aspects of Greek traditional culture, such as dances (Cowan 2016), behaviors are codified and socially meaningful, as a sign of power within the community, and as in many other cultures even the placement around the table is meaningful. In Tilos the rich repertoire includes mantinades of Cretan origin;14 songs structurally similar to mantinades, but in another dhromos15 and other songs deemed to be traditional. The tragoudhia tou trapezioú are widespread all over Greece, and I could not determine if (or to what degree) the Tilian repertoire includes songs from other regions besides Crete, which was also indicated to me by table companions in Megálo Horió. Kladakis and Lentakis told me that the repertoire is similar in nearby islands (Chalki, Kalymnos, Leros) and that in Karpathos they have sixty-five table songs.16 However, a scrupulous analysis of the origins would sometimes reveal that songs came into the tradition from “outside,” mainly from popular music. I have described elsewhere (Fabbri 2016, 2021) how “Tik-tak,” a song that I heard in Tilos only after 2005, described by local musicians as made known by a “viol player from Nysiros”, was recorded in Istanbul for Orfeon Records (Orfeon 11578) around 1912 by the Estoudiantina Tchanakas Smyrne (Kalydiótis 2002: 167), became a big success, and entered the tradition as one of the songs that characterize the good times in Smyrna before the katastrofí.17 As I discovered with the help of Neapolitan ethnomusicologists and record collectors, it was an adaptation in Greek of a Neapolitan song, “Questa non si tocca,” by Antonio Barbieri and Vincenzo Di Chiara, published by Bideri in 1910. In several of the recordings I made during the table songs performances, one of the attendees sings “Tik-tak,” but in the middle-eight interpolates the corresponding section from another song, Dhen se thelo piá (again, a Smyrnian cover of a Neapolitan song). Both “Tik-tak” and “Dhen se thelo piá” were made popular again in Greece by the release of a CD by the Estoudiantina Neas Ionias in 2003.18 One of the best-known songs in the dance repertoire of Tilos’ paniyiria, “Sta marmara tou Galata” (an authentic floor filler, if we are allowed to use the term) is known—also by distinguished ethonmusicologists—to have its origins in Karpathos, but a summary review of the lyrics raises some doubt.19

16There is no published collection of Tilian songs of the table, or of those sung during dances (the repertoires overlap). Ioannis Kladakis owns a precious fat notebook with many of the lyrics, and I heard that Filippas Lardopoulos would like to compile a collection, but it is clear that oral transmission is still the only way to perpetuate the tradition, as was demonstrated when a couple of young musicians were invited to the table a few years ago, and it became apparent that they did not know many of the songs.

17The tragoudhia tou trapezioú last nearly two hours, or even longer, supported by generous offerings of food and booze at the table. Often (not always) members of the small community stand up and dance in the very small space next to the table; then, it becomes clear that it is time to go, so everyone stands up, preceded by the musicians, and starts to sing (often the song of Agios Panteleimonas), walking down the steps that lead from the taverna to the churchyard.

Figure 7. Descending to the churchyard, Koupa, Megalo Horió, July 28, 2006

Photo by the author

- 20 Dum is the low-pitched sound of the doubeleki, alternating with the high-pitched tak.

18In the end, the musicians get to their reserved space, plug in their instruments, and start the dances. The change in the quality of sound is dramatic. Even if transducers and amplifiers have much better quality than twenty or more years ago, there is an obvious shift from the sound of unaltered voices and string instruments to the electronically filtered sound of their amplified versions: there is reverb added to the voice and the lyra, an emphasis on low frequencies, and the doubeleki’s dum sounds more like that of a kick drum in a drum kit.20 As I have said previously, this is what the dancers like, and nobody has ever told me (except in ethnomusicological conferences) that amplified music is not traditional anymore.

19As I wrote years ago:

The sound image of the descent from the table to the churchyard, with the following almost sudden change to amplified sound, has a strong symbolic value. It isn’t a migration from folk to popular, but a change of function within a traditional context. A passage from private to public, from sacred to profane, from oligarchy to people, from the church to the dhimos, from official patriarchy to familiar matriarchy. Greece, in other words: condensed in a small five-minute procession. (Fabbri 2010, 177; my translation)

20A change of function, that is what it is. In the small space of the taverna there is no need for amplification. Usually, the percussionist does not bring his doubeleki there, as its loud sound would overcome that of the lyra and laoúto, and that of the voices. But after the descent to the churchyard, dance becomes the primary function; in more than twenty years of attending paniyiria in Tilos, I have never heard complaints from Tilians about the quality or loudness of the sound, but, sometimes, about incorrect rhythm accents in the performance. The volume of the sound is aimed at creating a community, and this is not a new remark in music history, if we go back to rock festivals in the 1960s, or to the gemeinschaftsbildende Kraft (community-building force) attributed to the sound of a symphony orchestra by Paul Bekker (1918). Only a few Western European tourists make a face when the music accompanying a sousta is “too loud,” or if they see an electric bass or a drum machine in the band’s line-up. Let them complain.