In the spring of 1495, a deadly disease swept through Europe, leaving victims with severe physical and mental damage. The outbreak began during the military campaign of King Charles VIII of France in Italy. Historians say this was the first recorded outbreak of syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection that would later spread worldwide.

For decades, the origins of syphilis have remained a mystery. The timing of the 15th-century outbreak – occurring soon after Columbus and his crew returned from their voyages to the Americas – led many to believe the disease was brought to Europe through contact with the New World.

This idea, known as the Columbian Theory, suggests that sailors contracted syphilis in the Americas and introduced it to Europe.

Debating the origins of syphilis

Some experts argue that syphilis existed in Europe long before Columbus’s expeditions. The pre-Columbian theory proposes that syphilis was present in Medieval Europe but was misdiagnosed as other diseases. Supporters of this theory point to skeletal remains showing syphilis-like bone lesions that date back to before 1492.

Historical texts also describe illnesses with symptoms resembling syphilis, suggesting the disease may have been present but not recognized.

New clues from ancient DNA

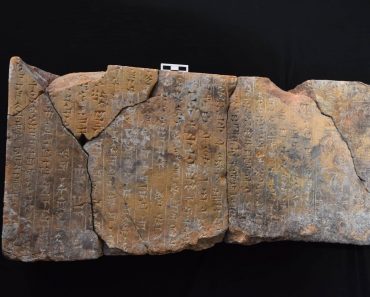

To resolve the debate, scientists have turned to ancient DNA analysis. In a recent study published in Nature, researchers led by Kirsten Bos and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology analyzed DNA from ancient bones.

The study involved samples from Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Argentina—regions where syphilis-like lesions appeared in historical remains.

“We’ve known for some time that syphilis-like infections occurred in the Americas for millennia, but from the lesions alone it’s impossible to fully characterize the disease,” said Casey Kirkpatrick, a paleopathologist who contributed to the study.

Findings from the Americas

Using advanced genetic techniques, the team recovered five ancient genomes related to syphilis. These findings suggest that the Americas were a center of diversity for treponemal diseases, which include syphilis, yaws, and bejel, long before Europeans arrived.

“We see extinct sister lineages for all known forms of this disease family,” said Rodrigo Barquera, a researcher who studied colonial Mexican bones. “… Syphilis, yaws, and bejel are the modern legacies of pathogens that once circulated in the Americas.”

Bos agrees. “The data clearly supports a root in the Americas for syphilis and its known relatives, and their introduction to Europe starting in the late 15th century is most consistent with the data,” she said.

A rapid global spread

This introduction to Europe may explain the explosion of syphilis cases after 1500. Human trafficking networks and European expansion into the Americas and Africa likely accelerated the disease’s global spread.

“While indigenous American groups harbored early forms of these diseases,” Bos explained. “Europeans were instrumental in spreading them around the world.”

The pre-Columbian debate continues

While the study supports the Columbian Theory, some evidence points to pre-1492 Europe. The Pre-Columbian Theory relies on skeletal remains with lesions resembling syphilis, but other diseases like leprosy or tuberculosis could cause these marks. Without definitive DNA evidence, the theory remains speculative.

Another perspective, the Unitarian Theory, suggests that syphilis, yaws, and bejel are variations of the same pathogen, Treponema pallidum, adapted to different climates. In tropical areas, the disease presents as yaws, in dry regions, as bejel, and in colder regions, as venereal syphilis. This theory argues that treponemal diseases have existed worldwide for thousands of years.

Mutation or evolutionary theory

A third hypothesis, the Mutation or Evolutionary Theory, proposes that syphilis evolved from a non-venereal form of Treponema pallidum already present in Europe or Africa. Changes in climate, social practices, and increased trade routes may have caused the pathogen to mutate into its sexually transmitted form.

Despite ongoing debate, the latest ancient DNA research brings scientists closer to solving the mystery. “The search will continue to define these earlier forms, and ancient DNA will surely be a valuable resource,” Krause said.

“Who knows what older related diseases made it around the world in humans or other animals before the syphilis family appeared.”

For now, the evidence points to the Americas as the origin of syphilis. But researchers continue to search for answers, knowing that each discovery adds another piece to this historical puzzle.