By Metropolitan Cleopas of Sweden

New Year’s Day, as a chronological landmark and a cultural symbol, is a subject of particular interest for the history of religions and cultural anthropology, and it constitutes a privileged field of study for understanding the ways in which societies ascribe meaning to time.

Therefore, the beginning of the year is not merely a calendrical convention, but a deeply meaningful event through which societies attempt to organize time, interpret the world, and situate the human being within it.

Let us attempt a brief comparative approach between the way in which the ancient Greeks perceived and honored the beginning of the year and the way in which Christians, throughout history—and especially during the period of the Byzantine Empire—celebrated New Year’s Day.

In ancient Greece there was no single, unified New Year. Each city-state determined the beginning of the year according to its own calendar, which was directly connected to natural and cosmic phenomena, such as the phases of the Moon or seasonal changes.

As Plutarch testifies (On Isis and Osiris), for the ancient Greeks time had primarily a cyclical character, reflecting the constant repetition of natural cycles.

In Athens, for example, the new year began after the summer solstice, with the month of Hekatombaion.

The celebration of the New Year among the ancient Greeks had chiefly a religious and cosmological character. It included sacrifices to the gods, rituals of purification, and festivals dedicated to deities associated with rebirth, vegetation, and the cycle of life.

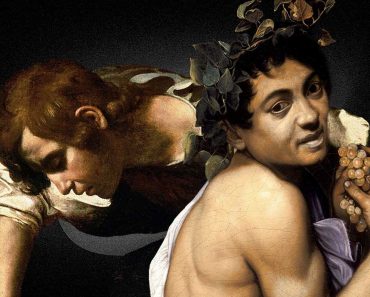

A special place was held by the Dionysian festivals, since Dionysus embodied the concept of rebirth, vital energy, and the transcendence of the old through the new.

Particularly widespread were apotropaic customs, such as the removal of the “old pollution” and the symbolic renewal of the household and the city.

The custom of the “good beginning” (agathē archē) was of particular importance: the first actions of the year were considered predictive of its outcome—a perception that survives to this day in popular tradition.

The change of the year did not have so much a personal or emotional character as a collective one: the aim was to secure the favor of the gods for the city and the harvest, harmony with nature, and the continuation of cosmic order.

The change of the year constituted an act of reaffirmation of the relationship between human beings, the city, and the universe.

With the prevalence of Christianity, the concept of time undergoes a radical transformation, and New Year’s Day acquires a theological and spiritual meaning. Time ceases to be cyclical and acquires a linear and soteriological dimension, with its starting point in Creation and its culmination in the Second Coming.

The human being no longer moves within an endless natural cycle, but within a history of salvation, which has a beginning, a climax, and an end.

January 1st is established as a day dedicated to the Circumcision of Christ and to the memory of Saint Basil the Great.

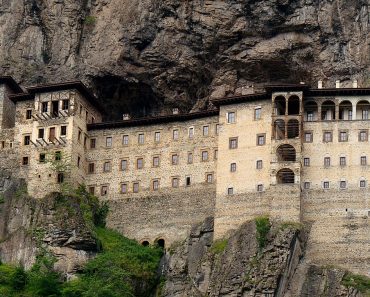

During the Byzantine Empire, New Year’s Day was fully integrated into the ecclesiastical and administrative framework of the state. Although the official Byzantine year began on September 1st—a date that coincided with the beginning of the Indiction—January 1st retained particular significance as a religious feast.

The celebrations included the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, prayer, self-restraint, and wishes for spiritual progress.

Saint Athanasius the Great, referring to the Divine Economy, emphasizes that renewal does not occur in time itself, but “in Christ,” who sanctifies every form of human temporality.

This theological position directly influences the way Byzantines experienced New Year’s Day—not with noisy festivities, but with liturgical seriousness, prayer, and almsgiving.

Saint John Chrysostom, in a homily on the beginning of the year, rejects secular notions of “good luck” and emphasizes the moral responsibility of the human person: “It is not time that makes actions good, but intention; and it is not the year that is good or bad, but the soul of the one who acts.” (On the Beginning of the Year, PG 56, 154)

This passage dismantles the magical perception of New Year’s Day and repositions it as an opportunity for moral and spiritual renewal.

Saint Basil the Great connects time with the practice of virtue: “Time is that which has been given to us for repentance; and in it each person stores up either salvation or judgment.” (Moralia, PG 31, 736) This passage endows the new year with a soteriological character.

It is noteworthy that, although Christianity differs radically from ancient Greek religion, certain elements of cultural continuity survive. The need for the blessing of the new year, wishes for health and prosperity, and the symbolism of renewal remain present, although they are reinterpreted within the Christian framework.

At the same time, customs emerge that bridge theological teaching and popular piety. A characteristic example is the custom of the Vasilopita, which is symbolically connected with the charitable activity of Saint Basil the Great.

This custom functions as a material expression of the blessing of the new year, incorporating the concept of Divine Providence into everyday life.

The historical course of New Year’s Day, from ancient Greek religion to Christianity, reveals a striking continuity through transformation.

From the preservation of cosmic balance and collective well-being, we move to a soteriological perspective; from the cycle of nature to the linear journey toward spiritual rebirth and deification.

Despite the differences, New Year’s Day remains a privileged point of convergence of history, theology, and human experience, and a religious, social, and cultural threshold: from the cyclical world of antiquity to the soteriological history of Christianity.