In a wide-ranging interview with TO VIMA INTERNATIONAL EDITION, veteran journalist Paul Taylor discusses inequality, economic fragility, media freedom, and the symbolic weight of Ellinikon – while brushing off claims of ideological bias as “flattering” and “revealing of deeper sensitivities.”

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis did not leave unanswered the recent article by Paul Taylor in The Guardian, which criticises the Greek government for the way in which growth is distributed, focusing particularly on the ongoing economic difficulties faced by the lower social strata.

What does Paul Taylor say in response to Kyriakos Mitsotakis following the criticism over his article in The Guardian?

Paul Taylor is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the European Policy Centre and also contributes as a columnist for The Guardian. He has spent nearly four decades working for the international news agency Reuters, serving as a correspondent, bureau chief, and editor in various cities across Europe and the Middle East. Over the course of his career, he has been posted in cities such as London, Paris, Tehran, Bonn, Brussels, Jerusalem, Berlin, and Cairo.

Your recent opinion piece for The Guardian provoked a rather sharp response from Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. Were you surprised by the strength of his reaction?

No, I’m not surprised that Prime Minister Mitsotakis would defend his record. It’s quite legitimate for him to do that. And if you look at the article, I think it’s a very balanced, factual column. I recognize the growth success of Greece, the sound public finances that the government has maintained. But I look at other factors that haven’t changed so much.

And you can obviously disagree legitimately over where to draw the balance between what has improved and what has remained unchanged.

I think that in terms of the inequalities, in terms of the nature of the economy, the dependency of the economy on a limited number of sectors, tourism, shipping, and real estate, in terms of the financial economy as well, that these are issues which Greek economists readily recognize when you talk to them. And so, I didn’t think I was saying anything wildly controversial.

While I was there, there was a general strike which was widely observed. Why was there a general strike?

Because not just the trade unions but a significant portion of the population feel that while the country’s macroeconomic situation may have got better, their individual situation has not. And there are reasons for that.

Greece is not the only country where that’s the case, obviously. But when you talk to – I use the phrase ordinary Greeks. I mean, non-elite Greeks, many people tell you that things have got no better, that the squeeze has got more difficult because rents have gone up in particular. People talk about rents more than – even more than I think they talk about prices. And I’m a friend of Greece.

I’ve been coming to Greece for a very long time. And the original genesis of the idea was when I was in Greece last summer and it was the 10th anniversary of the crisis, and the 20th anniversary of the boom in 2004 with the Olympics and winning the European soccer trophy and all of that. And so it just sort of struck me that Greece has this cyclical boom and bust history.

And therefore it led me to ask the question that many economists ask, which is, this time is it different? And I think my answer was very nuanced. It was so nuanced that my editors at The Guardian sort of said, so what’s your opinion? And I sort of said, well, my opinion is light and shadow. So I felt that I made a nuanced analysis of Greece pointing to the light and the shadow.

I didn’t put the demonstrators in the street either over the rail disaster and its follow-up or lack of follow-up, or over the general strike. But I happened to be there at times when it was clear that Greek public opinion is very concerned about these things.

Did you visit Greece last summer?

I saw this strike happening in the centre of Athens, and I was on my way to the Delphi Economic Forum. Many of my fellow delegates never managed to make it to the Delphi Economic Forum because of the strike, which shut down, as you know, the airport for a day and so on.

So I could not see the strike. But obviously, the strike reflected a build-up and public concerns, and the prime minister reacted to it and came out within days with a package of measures which he announced, which I’m sure were not unrelated to the social atmosphere in Greece. Last summer I was in Greece first as a tourist and then took advantage of that to look up one or two of my old friends and sources in Athens.

But I decided I needed to go back to Greece to do more reporting on this, and I took advantage of being in Greece for a week altogether around the Delphi Economic Forum to do that, plus telephone reporting, reading studies, talking to people in the EU institutions. I met people outside as well as people inside Greece. So there we are.

Let me say two things. First of all, I’m slightly surprised if it’s caused such a controversy. Obviously, there’s some sensitivity there.

I was flattered. The Guardian was flattered. The Guardian is an international newspaper. I think the Prime Minister compared us with a small Greek newspaper that has a niche readership, The Guardian has a global readership of about 9 million people.

My column, I was told by the editor today that my column had had 100,000 page views, so that’s quite good. And it got sort of like 690 or was it 960 comments in the chat page, which sometimes you get sensible comments and sometimes you get people who just want to let off steam.

Can I ask you about Mr Mitsotakis’ comments on The Guardian? He compares The Guardian to Britain’s equivalent of the ‘Efimerida Ton Sintakton’, suggesting ideological bias. How do you respond to that characterisation of the newspaper, and by extension, your work?

The Guardian is an independent, fact-based newspaper that does fact-based reporting. And probably in the spectrum of the British media, it’s sort of perhaps slightly to the left of the Greek centre, but it’s not some radical leftist newspaper or something like that. And as I say, it has a global reach and a global readership, and our European edition is doing very well. And so while I don’t want to comment on the Greek paper, but I don’t think it has the same positioning or the same kind of scale of readership. That’s all I would say.

But as I say, I’m both flattered and surprised that the prime minister should give us so much attention. But it suggests that there is a certain sensitivity there, and I understand that. And my wish is to be fair to Greece, to the Greek government, and I think that if you read the piece, it’s pretty balanced.

The prime minister described your criticism as not well-funded. What source and perspectives did you draw upon for this specific piece?

Probably not very much, just as you wouldn’t tell your sources if you were talking to a British newspaper about something you’d written about. No, I mean, I was at the whole of the Delphi Economic Forum. I heard a lot of discussion of the Greek economy there. I heard the prime minister speak, I heard the defence minister speak.

I met lots of Greek business people and Greek officials, some of whom I’d known previously, some not, and foreigners who interact with Greece and come to events like the Delphi Economic Forum.

And I asked them these sorts of questions. So how durable do you think this is? Will it last this time? What’s it based on? Is there a different kind of economy? Is there a different kind of society being built?

I went to sessions which talked about tech and trying to attract Greek people, particularly in the tech sector, back to Greece, which is tremendous.

But actually, there isn’t that much of it. And if you look at the statistics on the brain drain, they suggest that the brain drain has continued even after the official end of the programmes and of the financial crisis. And that Greece is still, unfortunately, losing brains.

So it’s a struggle. I recognise what the prime minister is trying to do, but it’s probably premature to say it’s successful.

The persistence of corruption and corruption deceptions. I think there’s been some improvement in tax collection, but I think there are still some gaps there. I certainly have encountered people in professions who continue not to give receipts.

The picture is different in the mainland from the islands. The islands remain very much a cash economy in a lot of areas. Even as simple things as getting a taxi to give you a receipt, I had acute difficulty with this last time I was there.

And one of the first words I learned in Greek, 15 years ago when I went there at the beginning of the financial crisis was apodixi. Try and get an apodixi from an Athens cab driver. You know these things.

I was with Reuters for 40 years. When I was in Greece during the crisis, it was as Reuters European affairs editor. I was standing bureau chief for a while in Athens during that period.

I got to know a lot of people there and got to dig a little bit deeper into how the society works. Quite recently, they produced some good reporting on local graft and how it still works. That’s a sort of eternal Greece story.

It’s not new. It’s not a scoop. But it’s one of those kind of warning signs that maybe there are important things that haven’t changed very much.

You know the degree to which the Greek state was enthralled to the two rival patronage systems of Neo Democratia and PASOK. Then arrived Syriza, which didn’t have its own patronage system. The question was, would they build their own patronage system like everybody else? Would they destroy the others? What would happen? I think the jury is still out on what happened.

Another thing, we need to talk about a little bit or refer to the issues over media freedom. Obviously, not just the scandal around the use of Pegasus programmes with journalists, but the excessive concentration, perhaps, of media ownership.

What kind of feedback did you receive after the publication of your article?

I have to be a little honest here and say that I haven’t really had time to analyse all the feedback comments we got from readers.

Sometimes I get more chance to sit down and look at them and read them. I have my own personal distribution networks, both by email to my own contacts and sources and so on, and on LinkedIn and on Facebook and on social media a little bit. Most of the comments I got were very fair.

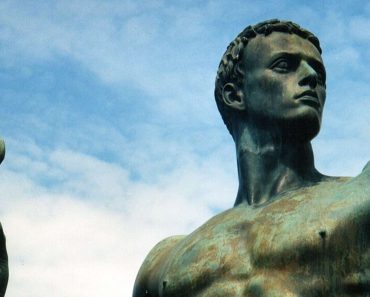

I have one from a Greek economist who told me how much he liked the fact that I told the story through the prism of the Ellinikon project. It’s hard not to. You’re a journalist.

We use our own eyes and ears. And as you’re flying into Athens each time, you fly over the old abandoned airport. And for 20 years of flying over it, nothing happened.

And then it became a refugee camp. And you know what you do as a journalist also, you try and use a set of thermometers. One of them, for example, there’s a little mall in central Athens just off Syntagma, between Kolokotroni and Syntagma. And that little passage, covered passage, I used to walk through every day from what was the old Reuters office opposite the National History Museum in Kolokotroni to Syntagma to go to Parliament or to go to the Finance Minister. The height of the crisis, every shop in that mall was boarded up.

There wasn’t a single shop there. The cafe had gone bust and so on. Now, you know, it’s booming again.

And you look at each year, that was one of my thermometers. So another thermometer was Ellinikon. And Ellinikon is an interesting story because it tells us so many of the different facets of Greece.

We are seeing buildings coming out of the earth. A lot of it still exists, mainly in that glossy brochure, which I’m sure you’ve seen.

But there are buildings coming out of the earth now. But again, what is this? Is this kind of the success of the new Greece or is it oligarchs building for foreigners or oligarchs building for other oligarchs? These are the sort of questions which I think are legitimate, Greek-friendly questions to Greeks.