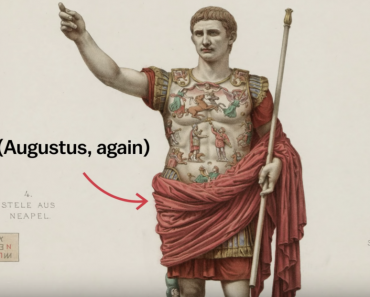

A 2,700-year-old ancient Greek helmet of the Corinthian type sits quietly inside the National Museum of South Korea, thousands of miles from where it was forged. The bronze helmet is registered as National Treasure No. 904 and is the only Western artifact to hold that status in South Korea.

It was discovered in 1875 at Olympia, Greece, during excavations near the Temple of Zeus. Archaeologists believe it was placed there as a votive offering. In ancient Greece, athletes and warriors often dedicated armor to the gods after victories or in hopes of divine protection.

From ancient Olympia to the modern Olympic Games

Olympia was the birthplace of the ancient Olympic Games. That link would later give the helmet a meaning far beyond archaeology. Its path to Korea became intertwined with one of the most politically charged moments in modern Olympic history.

That moment came in 1936. The XI Olympic Games were held in Berlin, staged by Nazi Germany as a display of power and ideology. The marathon race ended with a historic finish. Sohn Kee-chung crossed the line first in 2 hours, 29 minutes, and 19 seconds, setting a new Olympic record. His teammate, Nam Sung-yong, finished third.

Victory under colonial rule

They were the first ethnic Koreans to win Olympic medals. Yet neither competed under the Korean flag. Korea was under Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945. Korean athletes were forced to represent Japan in international competition.

Sohn was officially entered under the Japanese name Kitei Son, based on the Japanese reading of his name written in hanja. Olympic records listed him as Japanese.

Quiet resistance on the Olympic stage

Sohn did not openly challenge the rules. Instead, he resisted quietly. In interviews, he gave his Korean name. During the medal ceremony, as the Japanese anthem played, Sohn and Nam lowered their heads and avoided the flag. The act was subtle, but it was widely noticed.

After the race, Sohn told reporters he felt humiliated running for Japan. The reaction reached Korea quickly. The newspaper Dong-a Ilbo published a photograph of the ceremony with the Japanese emblem removed from Sohn’s uniform.

Japanese authorities responded harshly. Governor-General Minami Jiro ordered arrests and shut down the newspaper for months.

A disputed Olympic prize

Around the same time, the Corinthian helmet became part of an unusual Olympic proposal. A newspaper in Athens had acquired the artifact and planned to award it to the marathon champion as a symbolic link to ancient Greece.

At the National Museum of Korea, a Corinthian soldier’s helmet dating from the 6th century BC is displayed alone in the center of a hall.

In fact, this Greek helmet has been declared the 904th national treasure of Korea. pic.twitter.com/ztXaCJYroM— well-meaning (@FreshSummerWind) July 5, 2023

The International Olympic Committee rejected the plan. Officials ruled that the helmet’s value violated the amateur principles of the Games. The artifact remained in Germany, stored in a Berlin museum.

Returning the helmet to the Korean people

Decades later, the story came full circle. In 1986, during events marking the 50th anniversary of the Berlin Games, the helmet was formally presented to Sohn.

He declined personal ownership. Instead, he donated it to the National Museum of Korea, saying it belonged to the Korean people.

Sohn’s legacy beyond the marathon

Sohn later became a marathon coach and sports leader. One of his runners, Hwang Young-Cho, won gold at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Sohn also served as vice president of the Korean Olympic Committee and helped light the Olympic cauldron at the 1988 Seoul Games.

Sohn died in 2002 at age 90. In 2011, the IOC formally recognized his Korean nationality, while leaving historical records unchanged.

Today, the helmet stands as more than an ancient artifact. It connects ancient Greek ritual, modern sport, and Korea’s struggle for identity. Across nearly three millennia, it tells a story shaped by history, resistance, and memory.