National Opera House (O’Reilly Theatre), Wexford; 22/10/2025

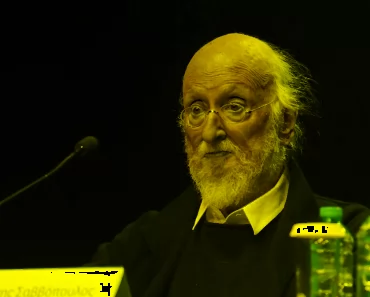

Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Opera; George Petrou (conductor/director); Sophie Junker (soprano); Sarah Gilford (soprano); Bruno de Sá (male sopranist); Nicolò Balducci (counter-tenor); Rory Musgrave (baritone); Petros Magoulas (bass).

Handel’s last opera for the London stage, ‘Deidamia’, is the subject of this second report from this year’s Wexford Festival Opera and a first hearing for this reviewer. For an opera seria, it has a fair bit of humour stemming from cross-dressing and lovers’ tiffs, but also seriousness in its treatment of the contradictions of heroism and the inexorability of fate. At a time (1741) when London tastes were turning to opera in English, Handel’s Italian libretto received only 3 performances, explaining at least in part his travelling to Dublin to lick his wounds, and his change to composing oratorios. Despite containing some of Handel’s most beautiful music, it was not revived until the mid-20th century. In this co-production with Göttingen International Handel Festival, both music and stage direction are provided by Greek conductor/director George Petrou. Set and costume design are by his compatriot Giorgina Germanou, while Daniele Naldi and Paolo Bonapace co-designed the lighting. All these creatives gave the production not merely a veneer but a thorough substance of excellence. However, the most unforgettable feature of the visuals was the ground-breaking projection, designed by Arnim Friess, which harnessed AI to achieve the frankly impossible. More about that later. Another unusual feature which worked to add hilarity (but also showed how knowledge of ‘myths and legends’ can aid our understanding of our own lives, was the use of supers dressed as modern tourists wandering through the ancient sites, oblivious of the characters visible to the audience, yet affected inexplicably by them. A Baroque orchestra includes a theorbo and a Baroque cello for continuos. The opera is sung in Italian with English surtitles.

The bones of the libretto are as follows. Achilles’ father Peleus has sent him to the island of Skyros, under the protection of his friend (and its king) Lycomedes, to escape the prophecy that if he takes part in the Trojan War, he will perish. [Achilles as a draft-dodger? I must refrain from puns about Achilles heels and bone spurs]. There he lives disguised as a young girl Pyrrha. He and Lycomedes’ daughter Deidamia are in love. Greek warriors Ulysses (under an assumed name Antilochus) and Phoenix arrive on Skyros to request military help for the Trojan War (which Lycomedes grants) and that he surrender the young Achilles, who is essential to Greek victory (Lycomedes denies that he is sheltering him but allows them to look). Phoenix falls for Nerea, Deidamia’s sister and confidante, but her suspicion of his motives and loyalty to Deidamia make it an awkward courtship. Pyrrha’s unconvincing femininity alerts the warriors’ suspicions, which they verify through wily trickery, unmasking Achilles. Nerea finally succumbs to the idea of eternal fame as the wife of a hero, but Deidamia is crestfallen, because she knows that Achilles will not return. An overt message of the opera is “make the best of the time you have; you’ll be a long time dead”, but the eponymous Deidamia says “no, there must be something better”. Even as I write it down, I must concede that it’s not particularly promising. But the music is ravishing. And in this production the visuals are next-level.

Belgian soprano Sophie Junker as Deidamia delivers with phenomenal vocal gymnastics with ornamentation, scales and cadenzas, but also a deep characterisation of a strong woman who rebels against fatalism and hero-worship and prizes love over all else. Achilles’ carelessness in maintaining his disguise dismays and angers her. One extraordinary AI projection accompanied her aria about freedom, with birds fluttering in time to the music, threatened by a dragon, then human forms, suggesting our freedoms are vulnerable. The few arias in the minor key are hers. In one, she muses over how her beauty will fade, as one of the tourist figures moves forward and ages before our eyes in projection. When Achilles choses fame and glory (and death) over her, her world lies in ruins.

Welsh soprano Sarah Gilford as Nerea sang a vocal line that was no less technically demanding and it received the same excellence of execution. Justifiably suspicious of Greeks bearing questions about Achilles and fiercely loyal to her sister, she fends off Phoenix’ attentions until the end when, with Achilles’ cover blown and more than a hint of giving in to the glamour of the warrior culture (and the fact that Ulysses has left his beautiful wife Penelope to fight the war), she relents and accepts Phoenix’ proposal.

The two formerly castrato roles, Achilles and Ulysses, are played by Brazilian male sopranist Bruno de Sá and Italian counter-tenor Nicolò Balducci respectively. Handel spares neither the same demands he makes of his women and both repay his confidence admirably. Dramatically, Achilles comes across as a big thoughtless self-centred kid, easily tricked into displaying his prowess at hunting (two direct hits on a fairground shooting gallery in the touristic back of the stage showing he could even shoot into the future), and arm-wrestling, not to mention unconvincing flirtatiousness with Ulysses. Picking a sword and helmet out of a box of jewels and trinkets clinched the betrayal. Ulysses, by contrast, is the dedicated patriotic warrior, shrewd and single-minded. With my modern ears, I find portraying that in a high voice rather incongruous. But what a voice.

Irish baritone Rory Musgrave was convincing as Ulysses’ equally focussed patriotic comrade, captivated by Nerea’s beauty. His duets with Ulysses and in particular Nerea held some of Handel’s most beautiful music. Greek bass Petros Magoulas was the majestic but ageing Lycomedes, mindful of fate and prophecy, loyal to his friends but ultimately also to Greece. A lovely aria in which he describes his earthly kingdom (and his need for a restful old age) was ironically delivered in a surreal undersea world with fish swimming around him. Quite magical.

One other astonishing and unforgettable piece of AI projection deserves mention. A mock trailer for the film ‘Ulysses’ with the principals and creatives of the production featured was quite extraordinarily ingenious.

This is a stunning production that lifts a mediocre libretto to the level of Handel’s music. Full marks from me.

Photo credit: Pádraig Grant