Revisiting Ancient China’s World Knowledge (a talk delivered at the Hong Kong Book Fair in July).

By the late 16th century, before Europeans arrived in China via sea routes, how much did ancient Chinese people know about the world? How did they imagine and understand the world they inhabited? This is not merely a question of intellectual history, but also one of the history of ideas, as it concerns the worldview of traditional China.

Ancient maps often reflect ancient people’s knowledge, concepts, and imagination of the world. Therefore, I will use a“world map” dating from the early Ming dynasty, specifically the early 15th century, and place it within the context of global history to discuss this issue.

**2**

Ryukoku University in Kyoto, Japan, is a university established by the Jōdo Shinshū Hongan-ji sect. It houses many treasures. Among them is the *Honil Gangni Yeokdae Gukdo Ji Do* (Map of Integrated Lands and Regions of Historical Countries and Capitals). Since its discovery over a century ago, this map has been highly regarded.

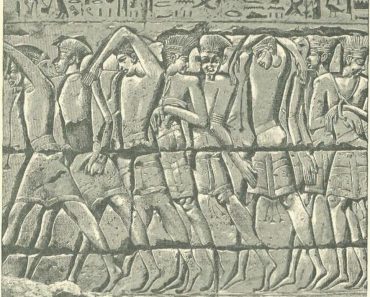

This map, painted on silk, measures 150 cm long and 163 cm wide. It was drawn by Koreans in 1402. As you can see, Korea is depicted quite large on the right side of the map – a clear expression of the Korean perspective. It’s important to understand that ancient maps were not merely what we now call“scientific geography” maps.

While modern maps primarily strive for objectivity, accuracy, and detail, ancient maps also contained national sentiments, worldviews, and even people’s prejudices and curiosities. Therefore, we can study them from the perspectives of intellectual and cultural history. In this way, maps become sources for the history of ideas.

Returning to this map. What was the basis for the Koreans drawing it? It turns out they relied on two earlier Chinese maps from the Mongol Yuan era: Li Zemin’s *Shengjiao Guangbei Tu* (Map of the Vast Reach of Imperial Teaching, 1330) and the monk Qingjun’s *Hunyi Jiangli Tu* (Map of Integrated Territories, 1370) from the late Yuan/early Ming period. Below this Korean map, a Korean official named Kwŏn Kŭn wrote a lengthy colophon.

From this colophon, we learn that Li Zemin’s map covered a vast“all-under-heaven,” thus providing knowledge of the Eurasian world spanning the Mongol Yuan era. Qingjun’s map, on the other hand, provided detailed geographical information on successive dynasties. The Koreans used these two maps as a foundation to create this new map.

However, being Korean, they felt these maps inadequately depicted“east of the Liao River” and their own country, Korea. So, they primarily supplemented Korean geography, adding their understanding of Japan further east, and conveniently enlarged Korea a bit. Therefore, while this map is a Korean work from the early Ming period, fundamentally, it reflects Chinese knowledge of the world from the Mongol Yuan era (1271-1368).

How did this Korean map end up in Japan? Many scholars speculate it was likely taken to Japan by the Japanese after the Imjin War (1592-1598). As is known, the Imjin War occurred during the Ming Wanli era. Toyotomi Hideyoshi of Japan invaded Korea to dominate East Asia.

Although Japan eventually withdrew under Ming pressure, they had occupied most of Korea and plundered many people and goods. This included various craftsmen, leading to the transmission of many Korean technologies to Japan, as well as books and paintings, leaving many Korean artifacts in Japan. After the war, although Korea sent several missions (“Sweeping Envoys”) to demand their return, many items and people remained in Japan.

This map was one such item. Japanese temples have a strong tradition of preserving artifacts. Many treasures from Tang and Song China, brought back, were stored in temples like Shōsō-in, Rinshō-in, and Shōren-in, acting like great treasuries. Due to historical reverence for temples in Japan, coupled with their armed forces and influence, artifacts were preserved exceptionally well. Even today, many treasures remain unknown, with new discoveries constantly emerging!

This map was no different. It wasn’t until the Meiji era that scholars recognized its significance. Because it was held by the Hongan-ji Buddhist sect and rarely shown, Professor Ogawa Takuji of Kyoto University meticulously copied it exactly. The version commonly used today is mainly this copy held by Kyoto University.

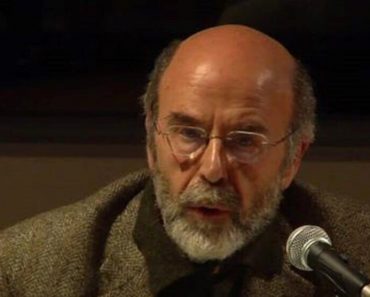

Professor Ogawa might not be widely familiar, but mentioning his three sons might help: Yukawa Hideki, the famous first Asian Nobel laureate in Physics; Kaizuka Shigeki, a towering figure in ancient Chinese history at Kyoto University who wrote on the *Shiji* and oracle bone inscriptions; and Ogawa Tamaki, a great professor of Chinese literature who interacted not only with Qian Zhongshu but also with senior scholars like Zhou Yiliang and Zhou Zumou.

**3**

This 1402 map raises fascinating questions.

The 15th/16th centuries were the era when new maritime empires began to eclipse old land empires and gradually dominated the world – the so-called“Age of Exploration” or the era of early globalization. First Portugal and Spain, then England and the Netherlands, reached every corner of the world via the oceans, occupying islands, ports, and deltas. Led primarily by colonists, merchants, and missionaries, they left no“terra nullius,” and Europe gradually became the world’s dominant power.

In this context, world knowledge became crucial. As the old saying goes,“Who possesses knowledge of the world, masters the world.” Hence, the“Age of Exploration” is also called the“Age of Discovery.” This is familiar territory:

* Dias (c. 1450-1500?; rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488)

* Columbus (1451-1506; reached the Americas in 1492, 1493, 1498)

* Da Gama (c. 1460-1524; reached India in 1498, 1502, 1524)

* Magellan (c. 1480-1521; circumnavigated the globe 1519-1521)

Hearing this, one might recall Zheng He. Zheng He’s voyages (1405-1433) indeed predated the Europeans. However, his primary purpose was not trade or commodity exchange, but rather to display imperial prestige. Though magnificent, it objectively did not promote globalization.

Yet, it was only *after* him that Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, and Vasco da Gama reached India via the Cape in 1497, giving Europeans a clearer picture of African geography. It is said that before the 1508 edition of Claudius Ptolemy’s *Geography*, Europeans lacked a complete map of Africa.

MENAFN18082025000159011032ID1109940928