This is part two of a special two-parter.

I cannot stress enough the need to click the videos in this email – and make sure your phone/computer is set to the loudest possible volume in order to maximize the musical joy.

I.

I devoted last week’s email to challenging the idea that the Ḥanukkah story is “Judaism vs. Greece.” All it took was a few clear examples from the works of Ḥazal to show how they embraced many aspects of Hellenistic culture. Ultimately, you’ll end up backing yourself into a corner if you want to claim that Ḥazal rejected Greece.

But as much as I proved that the “Judaism vs. Greece” narrative is facile, the obvious corollary to what I said isn’t that much better. Because an equally facile takeaway from last week would be that Ḥazal were Hellenists.

To better understand this – and to introduce more nuance into the discussion – we need better terminology for talking about everything I raised last week. And while I’ll get to that later, I want to first try a thought experiment – which I think perfectly captures the nuance needed.

II.

Imagine you’re attending a ḥasidic wedding when the band strikes up one of the most popular Jewish songs you’ll ever hear, Mordechai Ben David’s (MBD) hit 1986 song, Yidden (it starts at around the 18-second mark in the video below).

But, as the music starts, you turn to the band in shock. Because you know this tune – and it couldn’t be less Jewish.

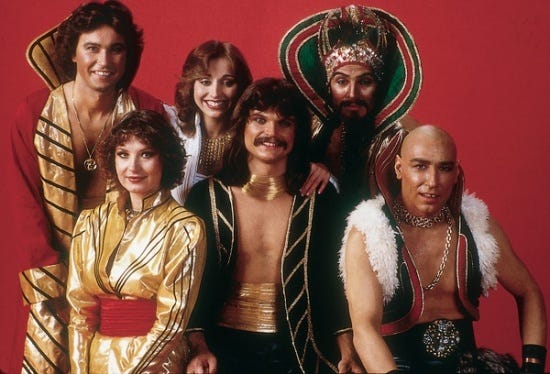

A grin spreads across your face as you realize what song the wedding band are actually playing: the disco hit Dschinghis Khan (we would pronounce it “Genghis Khan”), by the German band of the same name – performed at the 1979 Eurovision Song Contest (which, that year was held in Israel), which somehow only came in fourth place despite being an absolute belter:

And what’s so obvious but, nonetheless, so crucial to stress is that MBD’s Yidden doesn’t just sound like Dschinghis Khan, it is Dschinghis Khan.

But here’s the kicker: if you turned to one of the other guests at the wedding and tried to explain this to them, they wouldn’t know what you were talking about. Because, of the hundreds of people at the wedding, only you know what the band is really playing. You hear the band playing about as non-Jewish a song as you could ever find, Dschinghis Khan – but everyone else hears the super-Jewish Yidden.

And I think that Jewish music serves as the perfect example of how even parts of the Jewish world that see themselves as isolated from wider society have actually had that society infiltrate their lives – because it’s undeniable. You can be at a ḥasidic wedding where all the guests are dancing to 1970s German disco!

And what makes Jewish music an even better example is that, while Yidden might be my favorite illustration of this, it’s not the only example. Time and time again, songs we think of as quintessentially Jewish are clearly, obviously, undeniably non-Jewish in origin.

You can’t not listen to the hit single, Şımarık, by the Turkish popstar Tarkan, without thinking you’re at a Jewish wedding:

And for those of you who think of Benny and Gad Elbaz’s Hashem Melekh as some sort of 21st-century Jewish anthem, I have bad news for you – unless you’re also huge fans of Algerian music sensation Khaled. Though if that were the case, you’d already know that Hashem Melekh is really his bilingual (Algerian Arabic and French) hit C’est la vie:

(By the way, this isn’t a new phenomenon – the most popular tune for Ma‘oz Tzur is a German folk song. Though it would also be used later for one of Martin Luther’s hymns.)

Crucially for us, though, all of these examples illustrate two things. The first, at this point, is obvious: the claim that there are parts of the Jewish world that can remain isolated from wider society is false. No matter how insulated you think you are from wider society, if you’re rocking out to MBD’s Yidden you’re really rocking out to Dschinghis Khan.

But the second point – that is far more important than the first – adds a crucial modifier to the sentence above. Because it’s not that “if you’re rocking out to MBD’s Yidden you’re really rocking out to Dschinghis Khan,” it’s if you’re rocking out to MBD’s Yidden you’re unwittingly really rocking out to Dschinghis Khan. And this word “unwittingly” here is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

Because the trippy truth we need to accept is that, rather than there being one, single reality in which ḥasidim dancing to Yidden are really dancing to Dschinghis Khan, there are actually two different parallel realities.

In one reality, there is the hit 1979 song Dschinghis Khan, of which Yidden is a transparent knockoff. But in another reality – the reality inhabited by insular ḥasidim – Dschinghis Khan just doesn’t exist.

Indeed, from my limited research into all of this, MBD denies ever stealing the song – and I believe him. He claims that someone told him they had written this tune that would be perfect for him to put some words to, and he took it because it would obviously be such a hit.

And I believe him because while I grew up watching the Eurovision Song Contest – which means that I’d smell a rat the moment someone offered me the music to Dschinghis Khan – MBD grew up as a ḥasid in Brooklyn: insulated from the Eurovision Song Contest by virtue of not only being a ḥasid but also by being American.

And if all of this still doesn’t make much sense, I’ll use one final example to illustrate it all. This time it has nothing to do with Jews – other than the fact that the central character to the whole thing is the Israeli-American Haim Saban. Yes, I’m talking about Power Rangers.

(And given all the other amazing musical numbers I’ve given you an opportunity to hear, enjoy the opener to the original Power Rangers TV show. You’re welcome.)

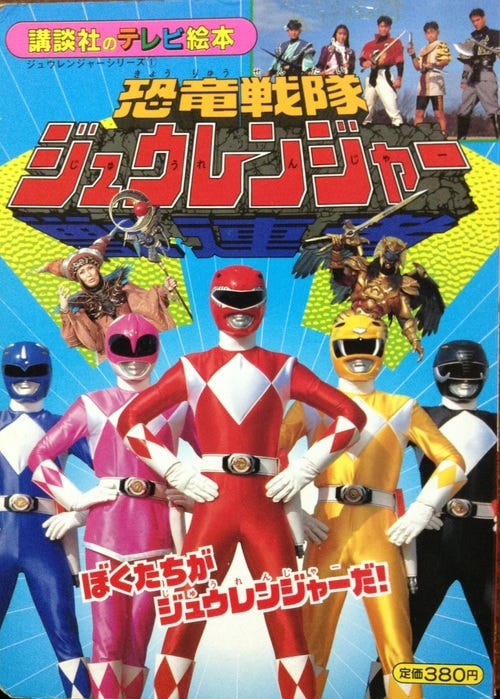

Because Power Rangers is actually the Japanese show Super Sentai. All Saban Entertainment did was splice action scenes from the Japanese show with other scenes shot with American actors – and in doing so, created a completely new show (which is why so many shots in the original series are used over and over again).

Once again, there are two realities. I look at the image above and see Power Rangers. But a Japanese person my age would see Dinosaur Squadron Zyuranger. And while Power Rangers is a transparent knockoff of Dinosaur Squadron Zyuranger, it doesn’t change the fact that all I see – even when I know the history of Power Rangers – is Power Rangers.

III.

At this point, we’re crying out for terminology. All the examples – all my talk of parallel realities – it could all be simplified with some better ways of speaking about it. So, here we go:

When a minority society lives amidst a larger one, the infiltration of the wider culture can happen in two different ways:

-

Absorption – Here, the community cannot help but absorb some of the wider culture and values surrounding them. A ḥasid in Brooklyn might not speak English at home, but it’s still a language they must use. Similarly, their political viewpoints reflect 21st-century America. No one was either a Democrat or Republican back in the heim – and no ḥasid had many thoughts on the impact of tariffs on the free market economy – but now they do. And musical tastes back in 18th-century Europe definitely weren’t disco.

-

Consciousness – Here, the community willfully meshes the wider culture with its own. English isn’t spoken reluctantly but intentionally: rabbis give derashot in English. Traditions of wider society become embraced – shuls have Super Bowl parties and Memorial Day BBQs. And no one needs to adapt Jewish versions of music to cater to the musical tastes that have been absorbed because everyone is more than happy to just listen to Bowling For Soup.

Obviously, these two concepts should be seen as two ends of a spectrum as there’s a lot of things that fall in between these two categories. And Ḥanukkah provides a good example of some of these: the dreidel is actually the German teetotum and gift-giving is certainly a co-opted Christmas tradition. But where they fall on the absorption/consciousness spectrum is less easy to determine.

And there’s also things that exist beyond the spectrum. Some ḥasidim in Brooklyn really don’t speak English – and not everything that a Jew could consciously embrace from wider society would be halakhically acceptable. It’s one thing to celebrate Thanksgiving, but another thing entirely to go trick-or-treating on Halloween or put up a Christmas tree in your home.

IV.

All of which brings me to the nuance needed to explore the real Ḥanukkah story. It’s not “Judaism vs. Greece” or even “True Jews vs. Hellenizers” but a story of “Absorption vs. Consciousness.”

What’s undeniable is that Jews have always absorbed things from wider society. It’s why, as I showed last week, Ḥazal spoke Greek and read Homer. But controversy has always raged over the conscious meshing of the two societies. And this is where it’s important to remember it’s a spectrum, because different members of Ḥazal existed on different parts of it. While the Mishnah forbids the teaching of Greek (Soṭah 9:14), for example, Rabban Shimon b. Gamliel permitted Sifrei Torah to be written in Greek (Megillah 9b).

The trap we can fall into is looking at Ḥazal’s use of the Greek word ὲπικῶμιον – that we pronounce afikoman (mPes. 10:8) – or songs like MBD’s Yidden as examples that prove that even the most insular Jew has allowed wider society to infiltrate to the same extent that we do.

But that would be a grave error. Because, while we might want to (politely) critique parts of the Jewish world for claiming to be insulated despite the obvious indication that they aren’t, the bigger issue is that, while they have absorbed wider society, we have consciously embraced it.

And while that embrace is the premise of the loose confederation of ideologies under the umbrella of “Modern Orthodoxy,” the willfulness with which we bring in the values and culture of wider society can be a problem. To use the most pareve example possible, it’s one thing for men to no longer wear a hat for davening because the President of the United States no longer wears a hat – but it’s another thing entirely to completely abandon davening because it’s not something valued by wider society.

V.

And this brings me to Asara be-Tevet – a fast day that’s primarily observed to commemorate the Babylonian siege on Yerushalayim in 588 B.C.E., but also includes a tragedy that took place two days earlier on the 8th of Tevet (which, this year, is today). As the Shulḥan Arukh explains, this was when the Torah was translated into Greek (O.Ḥ. 580:2).

And it can seem strange to claim that the translation of Tanakh into the lingua franca of the time is a bad thing – don’t we all benefit from English translations of Tanakh? And while there are many explanations of why it was a bad thing, I think there’s one particularly pertinent to what I’ve been saying.

Because the Greek translation of Tanakh – the Septuagint – isn’t just a translation, it reflects a fundamentally different cultural take on Tanakh. I’m most familiar with the Septuagint’s version of Esther, which makes two alterations of note. The first is that it has dragons in it – which, I’ll be honest, is an improvement in my book – and the second is that it adds many episodes in which Esther is more openly religious.

And while the latter may seem like a good thing, it completely warps how the story is read. By translating Tanakh, not just into a language but into a certain culture, the entire meaning and intent of the original is masked. And that’s a tragedy.

The Septuagint isn’t an example of adoption – “hey, we speak Greek, let’s make sure we can all read this” – it’s an example of consciousness: things are changed in order to conform with the broader society’s values.

And that should not just be a reason we mourn this Friday, but also serve as a cautionary tale for all of us.