Neither Greece nor her Diaspora have come to terms with some hard demographic facts. Both sides of the eternal Greek coin are living in a world of the 1970s or 1980s, if not in denial. I remember those years. I am a Gen Xer – I was a teenager in the late 1980s, living in Salt Lake City during the school year, and our ancestral island, Hydra, pretty much the whole summer. It was another millennium and truly, another world.

At that time, in the United States, as in other key Diaspora locations (Australia, Canada, Germany), there had been mass immigration, in some places, in several waves. Often, whole neighborhoods were Greek, the cultural and regional ‘syllogoi’ were well-subscribed, and lodge organizations boasted active, engaged, membership. Although it varied from place to place, churches, particularly in America, were full, and though both assimilation and intermarriage were proceeding inexorably, a sense of ethnic identity, together with the ability to speak Greek, remained normative. If a Greek Lobby ever existed, it was in the aftermath of the Cyprus invasion, as a large, upwardly mobile, and politically engaged Greek-American voter base combined with a few Greek members of Congress and staffers worked hard to force a short-lived arms embargo against Turkey in the mid-1970s.

Greece was at the end of a baby boom and decades of postwar economic growth, despite the distortions and traumas of civil war and dictatorship. Democratic, post-1974 Greece, whether right wing or left wing, was a middle-class society exceedingly homogeneous, which, while poor relative to the rest of Europe and its Diaspora, nonetheless had some diversification in the economy (along with a powerful merchant marine and tourism sector) and out-migration fell, both due to demographic slowdowns and improved economic prospects.

Fast forward nearly fifty years: most things have changed. Both the Diaspora and Greece are demographically hollowed out, in the former case due to assimilation and small or negative net migration, and in the latter, due to precipitous drop in the birthrate over decades along with mass, generally illegal immigration altering the demographic landscape. Greece in the 1980s was poor but upwardly mobile, with considerable affirmative endowments. Greece today is poor but downwardly mobile, with an educated populace conscious of this decline.

Despite this, both sides of the Greek coin continue to live in the past. Diaspora organizations and the Greek Orthodox Church continue to claim to speak for Greeks abroad, even as the organizations are often either defunct or facing attrition, sitting on properties or assets worth billions. The Church faces simultaneous problems of mixed marriages, converts who may not embrace the Greek in Greek Orthodoxy, a jurisdictional dance with Constantinople and the ‘paternalistic’ role of the Greek state.

The Greek Lobby is the ultimate Greek Myth, yet we continue to indulge the self-appointed, often Greek government-renumerated, advocacy organizations as representative of the Diaspora.

One would think, in a world of instant communications and cheap flights, that both sides would know each other better. The gap in the 1980s, with expensive flights and telephony, or in the early twentieth century, when my grandmother left Patras at 18 and returned once to Greece forty years later, was both understandable, yet in some ways less glaring than today. The global network of Greek merchant mariners, more active in the twentieth century than the twenty first, is a clear exception to this rule, but the lack of real knowledge today in an instant information era is hard to believe.

This goes both ways. Time and again Greeks in Greece believe that Greek America ends at New York; a private university rector in Greece asked if my South Carolina home was “close to New York,” and Greek Diaspora advocate rarely go beyond walking distance of the Grande Bretagne hotel in Athens. They have literally no idea of what is euphemistically called “The Greek Reality.”

We are complacent, even as demography in both places ticks along while we adjust the smartphone for our selfies. Our use of wifi and communications technology, it seems, is to upload selfies with prelates and politicos, preferably with a DC or Costa Navarino backdrop.

A solution, perhaps, is to leverage the facts on the ground, together with today’s and tomorrow’s technologies and trends. The increasing diversity of both the Diaspora and Greece needs to be empowered by Hellenism’s ‘Soft Culture’ rather than the hard edges of gatekeeper organizations or a Greek bureaucracy and business culture that discourages investment and innovation.

The Diaspora is more diverse and diffuse, yet engagement may still occur on a cellular level – via business contacts, the trade in ideas, and the multiplier effects of a technology ecosystem.

Off the top of my head, I can think of a half dozen technologists and game changers abroad who could help to foster and to found companies in Greece – often, crucially, employing dual use technologies useful to Greek national defense. These people are either actively or passively shut out by the Ottoman-style Greek bureaucracy, an ethos that extends to Greek consulates and, increasingly, to Greek organizations abroad ‘deputized’ with the Greek government’s favor.

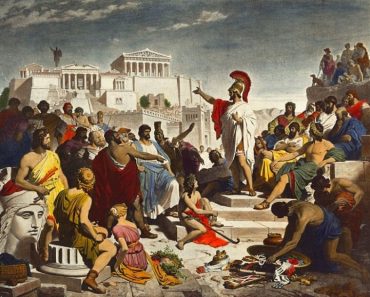

Further, we can look to history of past Greek diasporas, such as the commercial clans in the former Austria-Hungary, Egypt, Russia, and even the first Greeks in America, who leveraged their commercial and cosmopolitan contacts to birth the Greek state in the first place, and to sustain it in its tormented youth and adolescence. They observed the ‘facts on the ground’ and used the capabilities and technologies of the day, to change trajectories – economically, culturally, and militarily.

Greeks, whether at home or abroad, have always been asymmetrically successful when engaged and open minded – our choice.

Meanwhile, the clock ticks.