Recent archaeological research, as published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology by Leonie Hoff, brings to light intriguing insights into the artisans behind terracotta figurines from Thonis-Heracleion, an ancient Egyptian city located near Alexandria. Rediscovered submerged off the coast in the 1990s, this once-prosperous port city flourished from the 8th to the 2nd century BCE before succumbing to a natural disaster.

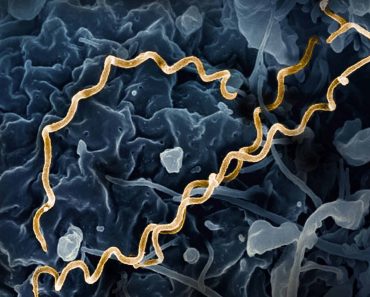

The study employs both modern technology and traditional archaeological techniques to analyze fingerprints on these artifacts, pinpointing the artisans who crafted them between the 7th and 2nd centuries BCE. This innovative approach provides unprecedented insight into the labor organization and cultural dynamics of ancient Egypt.

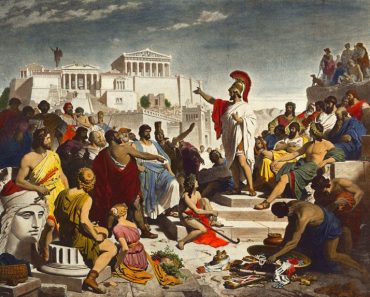

Thonis-Heracleion served as a crucial nexus for trade and cultural exchange between the Greek and Egyptian civilizations, maintaining its status as a cultural and economic hub until Alexandria’s rise. Within this rich historical context, the figurines offer valuable evidence of everyday life, craftsmanship, and cultural syncretism.

Key to the study are nine figurines, selected from over 60, bearing discernible fingerprints. Researchers utilized Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to analyze fingerprint ridge patterns, enabling them to estimate the age and sex of the artisans. Cross-referencing with contemporary fingerprint density studies, the analysis challenges previous assumptions about the gender-exclusive nature of this craft.

The findings reveal a diverse range of artisans, showing that men, women, and children all contributed to figurine production. This overturns the conventional belief that such craftwork was solely a male occupation and suggests a collaborative workshop environment where children apprenticed under adult supervision, indicating an organized training system.

Additionally, the fingerprints indicate a blend of cultural techniques and styles, with local artisans adopting Greek methods, such as the use of molds and finer materials. This fusion reflects broader cultural interactions and underscores the dynamic and cosmopolitan character of Thonis-Heracleion.

The involvement of women and children suggests a family-centered artisanal economy, unveiling a more equitable division of labor than previously recognized. Moreover, the differentiation between imported and locally produced figurines highlights cultural exchanges, with Greek influences favoring male artisanship and local creations showcasing diverse participation.

This groundbreaking research not only enriches our understanding of Mediterranean archaeology but also sets a precedent for further studies using fingerprint analysis across different ancient sites, potentially revealing common patterns and enhancing our comprehension of past social structures and artisanal practices.

SOURCES

Hoff, L. (2024) Fingerprints on figurines from Thonis-Heracleion. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 43: 399–418. doi.org/10.1111/ojoa.12308