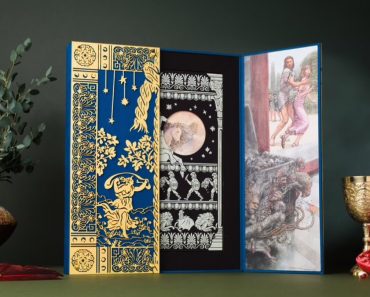

From the Midas touch and a Sisyphean task, to Pandora’s box and Achilles’ heel, characters from classical Greek and Roman mythology have an inescapable presence in everyday life and culture. The stories of these gods, goddesses, heroes and anti-heroes have been continually retold and reinterpreted in novels, poems, plays, music and in every type of visual art throughout centuries, from ancient Greek mythology paintings and sculptures to contemporary art.

With the rediscovery of classical antiquity in the Renaissance, the poetry of Ovid became a major influence on the imagination of poets and artists and remained a fundamental influence on the diffusion and perception of Greek mythology through subsequent centuries. The myth of Medusa has been interpreted by artists such as Rubens, Caravaggio and Bernini, the story of Venus was depicted by artists such as Botticelli and Tintoretto, while the labors of Hercules were portrayed by artists such as Luca Giordano and Antonio del Pollaiolo.

Learn more about some of the most famous Greek mythology paintings.

Featured image: Gustave Moreau – Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail), 1864. Image via Creative Commons

Raphael – The Triumph of Galatea

A fresco completed in 1514 for the Villa Farnesina in Rome, Caravaggio’s Triumph of Galatea depicts a mythological story of Galatea.

One of the fifty Nereides and the goddess of calm seas, she has been wooed by one-eyed giant Polyphemus with tunes from his rustic pipes and offerings of milk and cheese. However, she had spurned his advances and fallen in love with the peasant shepherd Acis. After catching the two lovers together, Polyphemos flew into a jealous rage and crushed the boy beneath a rock. Stricken with grief, the nymph transformed her young lover into a stream.

In the painting, Raphael decided to depict the nymph’s apotheosis while riding a shell-chariot drawn by two dolphins. As the art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote, the artist did not mean for Galatea to resemble any human person, but to represent ideal beauty.

Featured image: Raphael – The Triumph of Galatea, c. 1514. Fresco. Villa Farnesina, Rome. Image via Creative Commons

Gustave Moreau – Oedipus and the Sphinx

Painted in 1864, Gustave Moreau’s oil on canvas painting Oedipus and the Sphinx is a fresh treatment of the mythological meeting between Oedipus and the Sphinx on the road to Delphi, notably portrayed at Sophocles’ play Oedipus Rex.

On his journey between Thebes and Delphi, Oedipus found that the king of Thebes, Laius, had been recently killed and that the city was at the mercy of the Sphinx. In order to pass, Spinx gave Oedipus a riddle to solve. Failing to do so would mean his own death and that of the besieged Thebans. After he answered it correctly, the Sphinx killed herself by throwing herself into the sea and Oedipus became a king of Thebes.

Deliberately rejecting realism and naturalism which were popular in the mid-nineteenth century, Moreau adopted a deliberately archaic painting style and mythological subject matter. In the work, the Sphinx is on the offensive, clawing at Oedipus whose victory in the encounter is not yet assured.

Featured image: Gustave Moreau – Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864. Oil on canvas, 206 × 105 cm (81 x 41 in). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image via Creative Commons

Caravaggio – Narcissus

The story of Narcissus is one of the most retold one in literature, reinterpreted by writers such as Dante and Petrarch and depicted by many Renaissance artists, including Caravaggio.

According to the myth, Narcissus, a hunter from Thespiae in Boeotia, was known for his beauty. After getting thirsty during hunting one day, he leaned upon the water and saw himself in the bloom of youth. Not realizing it was his own reflection, he deeply feel in love with it, unable to leave the allure of his image. After realizing that his love could not be reciprocated, he dies of his passion, turning into a gold and white flower.

One of two Caravaggio’s on a theme from Classical mythology, the painting depicts Narcissus wearing an elegant brocade doublet and gazing upon his own distorted reflection. Locked in a circle with his reflection, the figure is surrounded with darkness, conveying an air of brooding melancholy.

Featured image: Caravaggio – Narcissus, 1597–1599. Oil on canvas, 110 × 92 cm (43 × 36 in). Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica. Image via Creative Commons

Peter Paul Rubens – The Fall of Phaeton

Painted by the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, the painting depicts the ancient Greek myth of Phaeton, a recurring theme in visual arts.

Phaeton was the son of the Oceanid Clymene and the solar deity Helios. After asking Helios for some proof that he was indeed his son, the god promised to grant him whatever he wanted. After he insisted on being allowed to drive the sun chariot for a day, Helios tried to dissuade him with no luck. Eventually, he was placed in charge of the chariot, but unable to control the horses, he came too close to the Earth and Zeus struck him down with a thunderbolt to prevent a disaster. In the process, Phaeton fell from the chariot to his death.

In the painting, Rubens decided to depict the myth at the height of its action, as Zeus’ thunderbolts hurl towards Phaeton’s chariot. The butterfly winged female figures around him represent the hours and seasons, reacting in terror as the night and day cycle becomes disrupted by the accident.

Featured image: Peter Paul Rubens – The Fall of Phaeton, c. 1604-1605. Oil on canvas, 98.4 x 131.2 cm (38.7 x 51.6 in). The National Gallery of Art. Image via Creative Commons

Giorgio de Chirico – Ariadne

A Cretan princess in Greek mythology, Ariadne fell in love with Theseus, who volunteered to kill the Minotaur, a fabulous monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull sent to Minos by the god Poseidon for sacrifice. To help him succeed, she provided him a sword and ball of thread so that he could retrace his way out of the labyrinth of the Minotaur. After he killed the beast, she betrayed her father and her country and eloped with Theseus. However, he abandoned her sleeping on Naxos, where Dionysus rediscovered and wedded her.

In this early 20th-century painting, Giorgio de Chirico depicted Ariadne as she lays sleeping in an empty public square. According to sources provided by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the work reflects de Chirico’s personal feelings of isolation after moving to Paris in 1911.

Featured image: Giorgio de Chirico – Ariadne, 1913. Oil and graphite on canvas, 135.3 × 180.3 cm (53.3 × 71 in). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image via Creative Commons

Peter Paul Rubens – Leda and the Swan

Rubens’ painting Leda and the Swan was painted after Michelangelo‘s take on the subject.

According to Greek mythology, the god Zeus, in the form of a swan, seduced Leda on the same night she slept with her husband Tyndareus, the King of Sparta. Later, Leda bore Helen and Polydeuces, children of Zeus, while at the same time bearing Castor and Clytemnestra, children of her husband Tyndareus, the King of Sparta. In some versions, she laid two eggs from which the children hatched.

Women being seduced by divinities was a recurring subject in Renaissance and Baroque, often portrayed in a sensual manner. Rubens depicted Leda fully nude as the swan caresses her on her most intimate area with its neck cradled between her breasts. The swan is depicted as a graceful animal who also can ravish.

Featured image: Peter Paul Rubens – Leda and the Swan, before 1600. Oil on panel, 64.5 x 80.5 cm (25.3 x 31.6 in). Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Image via Creative Commons