Google DeepMind has unveiled an artificial intelligence tool named Aeneas that promises to transform how historians study ancient Roman inscriptions. Named after the mythical Trojan hero, this revolutionary AI system can predict missing words in damaged Latin texts, determine where and when inscriptions were created, and identify historical connections between different texts across the Roman Empire, reports The Guardian. The tool could be a leap in digital archaeology, offering historians capabilities that would traditionally require decades of specialized knowledge to develop.

Developed through collaboration between Google DeepMind and Dr. Thea Sommerschield at the University of Nottingham, Aeneas was trained on an enormous database of nearly 200,000 known Roman inscriptions containing 16 million characters. The AI system can analyze fragmentary Latin texts from the 7th century BC to 8th century AD, providing contextual information that helps historians understand the social, political, and cultural significance of ancient writings carved in stone across the Roman world.

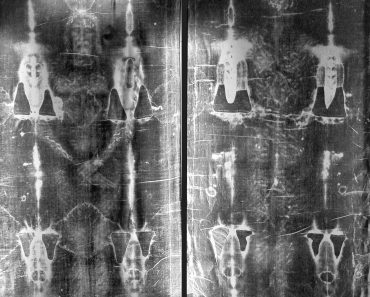

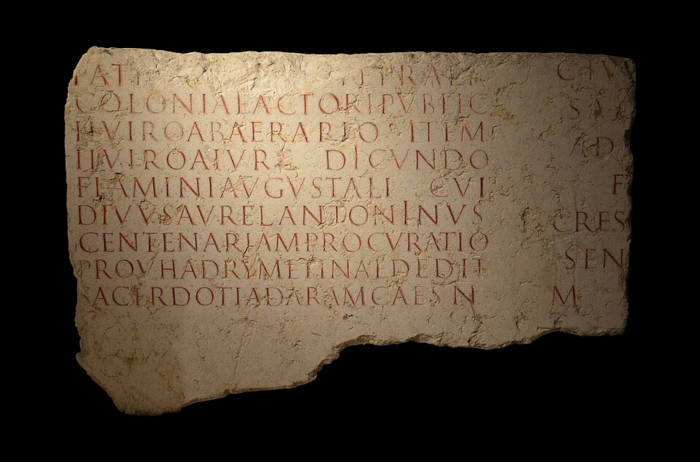

Ancient Roman inscription showing the type of Latin epigraphy that the Aeneas AI system can analyze and interpret for historical context. Arnaud Fafournoux/ CC BY-SA 3.0

Transforming Historical Research Through AI

The Nature journal study reveals that Aeneas can assign inscriptions to one of 62 Roman provinces with 72% accuracy and estimate when texts were written to within 13 years. Unlike simple word-matching algorithms, the AI identifies deeper historical connections between inscriptions, linking texts through subtle linguistic patterns and cultural contexts that might escape even experienced epigraphers.

In testing, researchers challenged Aeneas to analyze the famous Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus Caesar’s autobiographical inscription carved into monuments across the Roman Empire. The AI proposed two potential dating periods – either the first decade BC or between 10-20 AD – precisely matching the scholarly debate that has continued for generations. This demonstrates the system’s ability to capture the nuanced uncertainty that characterizes much of ancient historical research.

Professor Mary Beard of Cambridge University described the tool as “transformative,” while University of Oxford’s Jonathan Prag noted that Aeneas would “enable a wider range of people to work on the texts” by democratizing access to the specialized knowledge traditionally required for epigraphic research.

Bridging Ancient and Modern Worlds

Roman inscriptions represent some of humanity’s most direct connections to the ancient world, encompassing everything from imperial decrees and political graffiti to love poems, business records, and epitaphs. Dr. Sommerschield emphasizes their unique value:

“What makes them unique is that they are written by the ancient people themselves across all social classes. It’s not just history written by the victors.”

The challenge facing scholars is immense – an estimated 1,500 new inscriptions are discovered annually, many fragmented or weathered beyond easy interpretation. Traditional analysis requires extensive personal knowledge built over decades, limiting the number of researchers who can effectively work with these materials.

Aeneas addresses this bottleneck by providing rapid contextual analysis. In a remarkable demonstration, the AI analyzed inscriptions on a votive altar from ancient Mogontiacum (modern Mainz, Germany) and revealed through linguistic similarities how it had been influenced by an older altar in the region – connections that provided “jaw-dropping moments” for the research team.

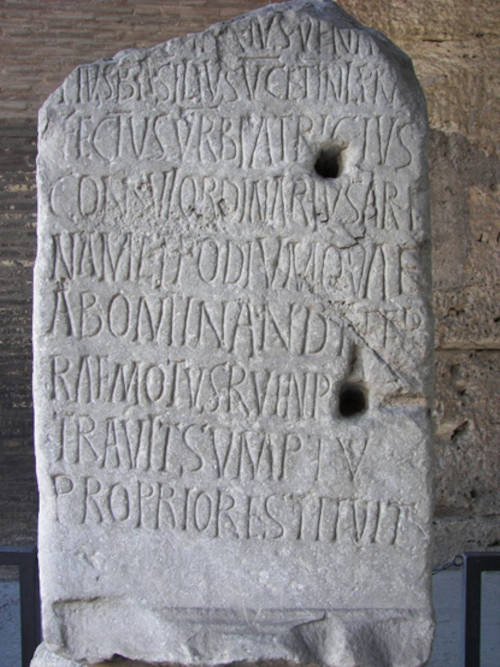

Ancient Roman inscription from the Colosseum showing the type of Latin epigraphy that Aeneas can analyze. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Critical Limitations: The Perils of AI Text Reconstruction

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding Aeneas, several leading epigraphers have raised significant concerns about the AI’s text restoration capabilities. The system’s ability to “fill in gaps” in damaged inscriptions – perhaps its most publicized feature – has only been tested on known inscriptions where researchers deliberately blocked out existing text, creating artificial rather than genuine omissions, as is acknowledged in the study.

The problem lies in the nature of ancient inscriptions themselves. Unlike modern texts that follow standardized formulas, Roman inscriptions often contain unique personal expressions, local dialectical variations, or deliberate departures from conventional phrasing. As noted in previous research on AI limitations in historical texts, “the most historically significant inscriptions are often those that break the mold – precisely the texts where formulaic AI predictions would be most unreliable” writes an earlier Ancient Origins article.

The Risk of Circular Reasoning

A fundamental concern involves the AI’s training methodology. Since Aeneas learned from existing inscription databases, it may simply reproduce the interpretative biases and restoration choices of previous scholars rather than offering genuinely new insights. When 19th and early 20th-century epigraphers reconstructed damaged texts, they often filled gaps based on their assumptions about Roman society, language, and culture – assumptions that modern scholarship has sometimes overturned.

The Guardian report notes that while historians found the tool helpful in 90% of cases, this evaluation focused primarily on contextual analysis rather than text restoration. The distinction is crucial, as providing historical context differs significantly from reconstructing specific missing words or phrases.

Cultural and Contextual Blindness

The Aeneas research team acknowledges in their Nature publication that text restoration has only been tested on artificially created gaps, not real damage from weathering, deliberate defacement, or archaeological accidents. Real lacunae often occur at precisely the most crucial points – names, dates, or key phrases that would completely change an inscription’s meaning.

As Dr. Sommerschield emphasized:

“We always stress that any text restoration suggestions should be treated as hypotheses requiring scholarly verification. The AI can suggest possibilities, but it cannot determine historical truth.”

This limitation becomes more significant when considering that similar AI approaches to ancient texts have faced criticism in the past. Previous research on AI decoding of ancient Greek texts noted concerns about overconfidence in algorithmic interpretations when applied to genuinely fragmentary materials.

Academic Caution and Professional Standards

Professor Jonathan Prag of Oxford University, a co-author of the Aeneas study, acknowledged these limitations in the Nature paper, stating that users “need to be able to use it critically.” This caveat becomes crucial when considering that incorrect text reconstructions could influence interpretations of ancient law, religion, politics, or social structures for generations of future scholars.

The consensus emerging from the scholarly community appears to be that while Aeneas excels at dating and geographical attribution – tasks based on broader patterns in the data – its text restoration capabilities require extremely cautious application until more rigorous testing on genuinely damaged inscriptions can demonstrate reliability beyond artificial test scenarios, as noted in the comprehensive Nature evaluation.

Top image: Fragment of a bronze military diploma from Sardinia, issued by the emperor Trajan to a sailor on a warship. 113/14 CE (CIL XVI, 60, Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Public Domain

By Gary Manners