A groundbreaking genetic study has revealed that the DNA of the inhabitants of Mesa Mani (Inner Mani) constitutes a unique “genetic island” in Europe. Due to geographic isolation spanning over ten centuries, the population remains one of the most genetically distinct on the continent.

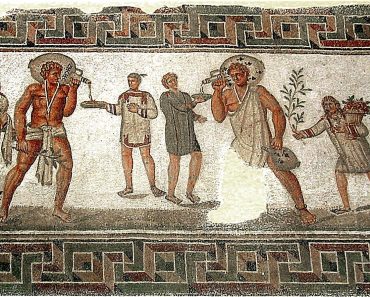

The findings, published on Wednesday in the journal Communications Biology (Nature Portfolio), demonstrate that many ancestral lineages of current residents can be traced back to the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, and the Roman period within the Greek region.

Mani: A land of stone and autonomy

Mesa Mani—the rugged region south of Areopoli characterized by wild mountains, dramatic coastlines, and iconic stone towers—has long fascinated travelers and historians, including Jules Verne and Patrick Leigh Fermor. The resilient character and martial spirit of the Maniots allowed them to maintain autonomy against successive conquerors. Notably, the people of Mani played a pivotal role in the Greek War of Independence in 1821.

An international research team—comprising scientists from the University of Oxford, Tel Aviv University, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, the Areopoli Health Center, and European University Cyprus—focused on the origins of this unique population.

“This is a region of mainland Greece unlike any other,” says lead author Dr. Leonidas-Romanos Davranoglou. “With its war towers, archaic dialect, and unique customs, we wanted to solve historical riddles and give a voice to fading traditions.”

Scientific methodology for Mani’s DNA

Researchers analyzed genetic material from over 100 male residents using innovative molecular techniques provided by FamilyTreeDNA—the laboratory famous for isolating Beethoven’s DNA. This data was compared against thousands of ancient DNA samples and a global database of 1.3 million contemporary individuals.

The results confirm that Mesa Mani is a genetic “time capsule.” Unlike much of mainland Greece and the Balkans, the population shows almost no evidence of admixture from the Slavic migrations of the 6th century AD, which drastically altered the genetic and linguistic landscape of Southeast Europe.

“For at least 1,400 years, the people of Mesa Mani were extremely isolated,” Dr. Davranoglou explains. “They are likely the direct descendants of the same people who built the region’s unique megalithic structures.”

Identity beyond genetics and key findings

Dr. Davranoglou emphasizes that “Greekness” is a cultural trait, not a genetic one. “DNA helps us illuminate unknown aspects of history, but it doesn’t define identity. While the Maniots remained isolated, all humans are ultimately mixtures of different populations. Genetics brings us together; it doesn’t divide us.”

A Common Ancestor: Over 50% of modern Mesa Maniot men descend from a single male ancestor who lived in the 7th century AD. This suggests a “population bottleneck” caused by war or plague, followed by centuries of isolation.

Patriarchal Structure: While paternal lines show long-term local continuity, maternal lineages suggest limited contact with the Eastern Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and Western Europe. This reflects a strictly patriarchal society where men remained rooted while a small number of foreign women were integrated into the community.

The study combined genetics with oral histories and archival research. Local artist Michalis Kassis noted: “It is no coincidence that no conqueror ever established a foothold here. The land was merciless. Stones, sun, and sea—that is Mani. Fertile soil does not easily produce heroes.”

Moving forward, the team aims to use this genetic map to identify clinical markers and hereditary diseases. Professor Theodoros Mariolis-Sapsakos and Dr. Anargyros Mariolis noted that understanding the “genetic shield” of Mesa Mani could lead to better public health strategies and serve as a model for studying other isolated populations in Greece.