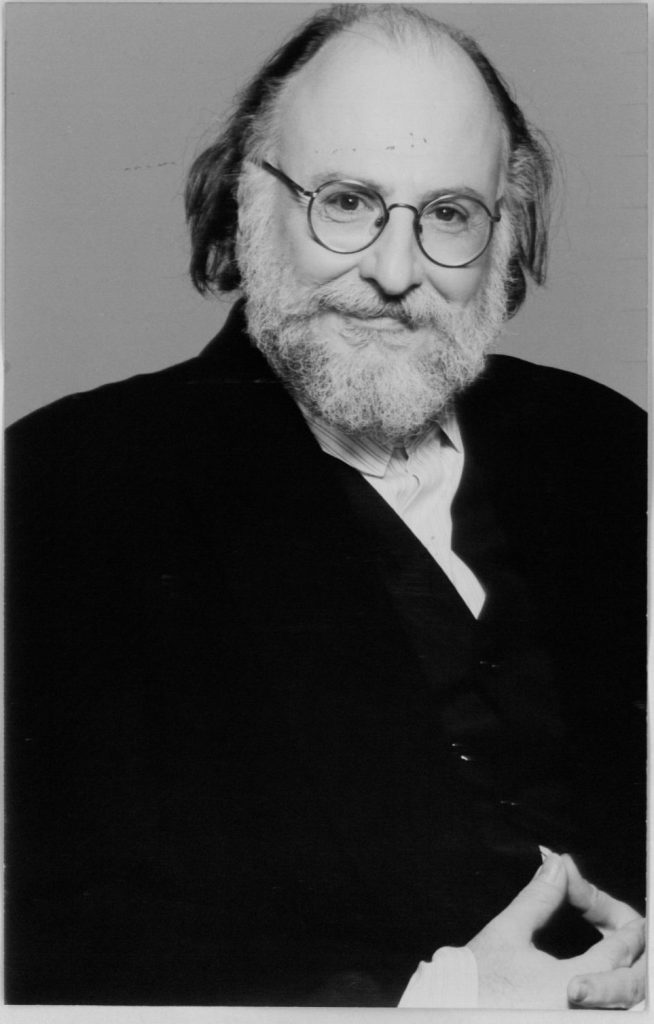

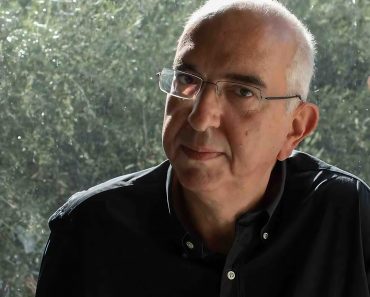

Dionysis Savvopoulos, the legendary Greek singer-songwriter who shaped the post-1960s sound of Greece, passed away on October 21 — coinciding with the anniversary of his iconic album “To Perivoli tou Trellou” (“The Madman’s Orchard”) in 1969. Known for influencing the generation of the ’60s, Savvopoulos’s music fused social awareness with lyrical artistry, leaving an indelible mark on Greek culture.

In memory of his passing, we return to a 1975 interview he gave to Giorgos Pilichos for the magazine Tachydromos, where, ten years into his career, Savvopoulos reintroduced himself to the world.

“Maybe you know, but a truck brought me here. From a place so distant that sometimes I doubt it even exists. That place is called Thessaloniki, and here it’s called Athens — and it’s shameful!”

He marveled at the young people who left their small worlds behind, arriving in the capital to give everything — even what they didn’t have to spare.

“The truck is a magical thing. You know, the national road, bitter laurels, plastic bottles on the roadside, ironworks, jukeboxes… and finally, Omonia Square. Twenty years earlier, the director Nikos Koundouros called it a huge hole, yet it refused to remain one, shining instead. In the summer of ’65, Omonia became a stage where the best young people protested — now, they’re called provocateurs! Such confusion of language, God!”

Arriving in 1963 with only 100 drachmas, Savvopoulos recounts his first night eating at the legendary Tsitsanis tavern, listening alone to the song “Archontissa”. Soon after, he tried to join the choir for Hadjidakis and Theodorakis’s “Magical City” at the Park, and encountered Mános Loïzos, another future giant of Greek music.

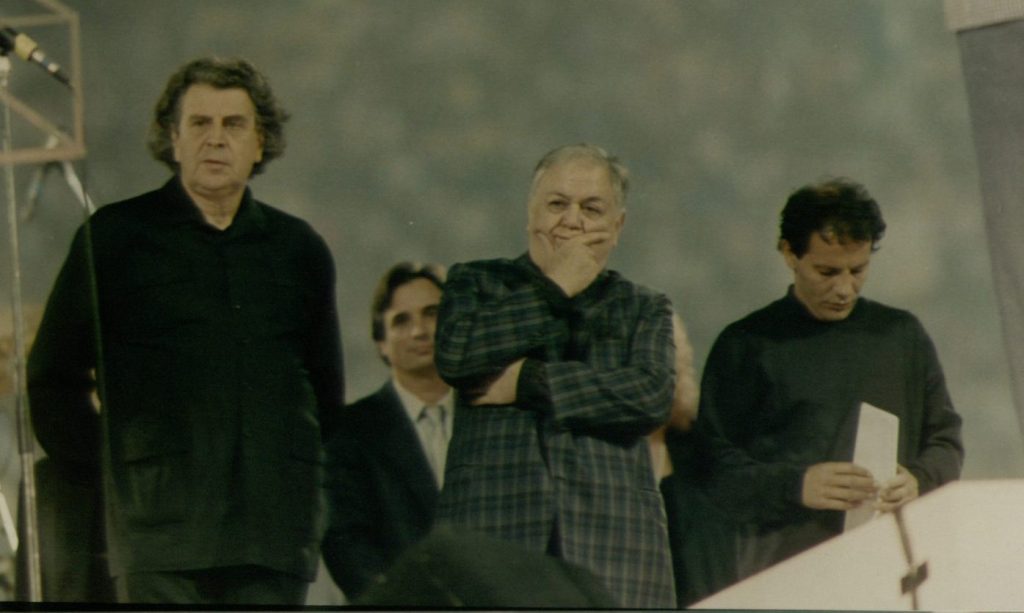

“He couldn’t get me a job, but he took me in at his home in Tavros, taught me guitar… until a misunderstanding about my youthful bluntness led him to kick me out. Afterward, we reconciled, and we became great friends. Later, we worked together at Giorgos Koundouros’s Stoa, with Maria Farantouri on vocals. I had no real success back then, except once alongside Mikis Theodorakis — remember that?”

The First Record and Life Struggles

His first record, under the guidance of Nikos Mamangakis, came out in February 1965. The EP featured four songs: “Egerterio”, “A Small Sea”, “The Birds of Misfortune”, and “Don’t Speak of Love Anymore”.

Savvopoulos’s early life was marked by hardship and adventure. He worked odd jobs, from journalist to nude model at the Athens School of Fine Arts, often relying on the kindness of fellow musicians. During the summer of 1964, homeless and hungry, he would sleep outside, leaving posters encouraging people to “walk too” in public spaces.

“By luck, Giannis Markopoulos took me in for a long stay in Kypseli. I was a burdensome, annoying guest, but he eventually accepted that I was just clever and curious.”

The 1960s Athens music scene was a fertile, competitive ground. Young musicians improvised around the spaces left by Hadjidakis, Theodorakis, and others like Stavros Xarhakos. Savvopoulos recounts the angelic energy of those early arrivals, each from distant corners of Greece or abroad, converging in the city to create a new musical culture.

Albums of Power and Nostalgia

“The Truck” (To Fortigo), released in November 1966, featured seventeen songs, though five were censored by the authorities — a reminder of the strict cultural controls under the Greek junta era. The album’s defining feature was its raw, breathtaking energy.

After a brief hiatus abroad, he returned with “To Perivoli tou Trellou”, written in Italy between 1968–69. Its theme is nostalgia — not for any specific event, but for life itself in its purest, healthiest form.

“The motifs of power and nostalgia appear again in Ballos and Vromiko Psomi. Ballos became particularly successful, its emotional resonance felt almost like a mythic statement of responsibility to the audience. ‘What’s happening?’ became a beloved catchphrase that year at Rodeo.”

Politics and Personal Beliefs

Savvopoulos describes his complicated relationship with political ideology:

“I have never signed any declaration of political allegiance, though I find it entertaining to consider here. I am a strange type of leftist, born during the Civil War, unwilling to follow its terms blindly. I refuse to belong to any party because joining would perpetuate the impasse our people have faced for decades. I vote for nothing, saving myself for something better.”

He criticizes the reduction of humans to mere socio-economic actors, arguing that revolution and socialist ideals are fueled by the excess, creativity, and individuality of human beings — the very traits that cannot be fully controlled by authority.

“Socialist revolution is more than a social event. It is the productive reclaiming of time and space, restoring tradition and creating a rare, unique future. This is Marxism’s justice, possible thanks to the excess of human existence.”

.jpg)