Before apocryphally rolling out of the carpet and stepping into legend, Cleopatra (69 BC-30 BC) already had a storied past. The 21-year-old and her 13-year-old brother-husband Ptolemy XIII (62 BC-47 BC) ruled together for nearly two years before said brother, influenced by overly ambitious advisors, banished Cleopatra from Alexandria.

Prudently using her mastery of the Egyptian language—the first Ptolemy to do so in the nearly 300-year-old dynasty—Cleopatra raised an army to defeat her brother, Ptolemy XIII. It was only shortly thereafter that she had the legendary encounter with Caesar. Yet most of what has been written about Cleopatra concerns her entanglement with ancient Rome—that is to say, it was written from a decidedly biased Roman perspective. Time and again, we hear about Cleopatra as the subversive siren from the East who seduced two of ancient Rome’s greatest generals.

Cleopatra’s Forgotten Lineage: More Greek Than Egyptian?

What could account for so much ire against the Egyptian queen? The truth is, in order to justify an unpopular civil war against his rival Marc Antony (83 BC-30 BC), Gaius Octavius “Octavian” (later Augustus—63 BC-14 AD) launched first a propaganda campaign then a full-scale war against Egypt. He did so by painting Cleopatra as an Eastern harlot who seduced Antony with her depraved sorcery. This view soon took hold in the imaginations of the xenophobic and misogynist Romans. In his Odes, Horace calls her a “fatal monster,” Sextus Propertius refers to her as the “whore queen” in Elegies, and in Lucan’s Poems she is termed “Egypt’s shame.” What is never mentioned about the Egyptian queen is that she may not have had a drop of Egyptian blood. In fact, her lineage may have derived from a Macedonian Greek whose military accomplishments were the ambition of every Roman leader.

It is ironic that the Romans glorified Alexander the Great (356 BC-323 BC) and disdained Cleopatra, who was not only Alexander’s political heir but may very well have been his biological heir as well. Ptolemy I Soter (367 BC-83 AD), the founding member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, was one of Alexander’s three most trusted Macedonian generals and by some accounts, his half-brother as well.

While vilified in the Greek city-states, polygamy was practiced in the Greek kingdom of Macedonia, especially amongst the ruling class. Phillip II (386-336 BC), Alexander’s father, had several wives and many children, Ptolemy among them. Alexander even had a sister named Kleopatra, which in Greek means “glory of the father.” Cleopatra was, in fact, a common name amongst queens in Ptolemaic Egypt. Alas, Cleopatra’s link to Alexander continued after her demise; the Hellenistic period begins with the death of Alexander and ends with the death of Cleopatra.

Bust of Cleopatra. (Public Domain)

Architectural Marvels: The Lighthouse and the Great Library

After Alexander’s death, his empire was divided between his three generals, with Ptolemy winning the grand prize of Egypt. Alexandria, founded by Alexander in 331 BC, had become Egypt’s new Hellenistic capital. Because of the location of Alexandria’s port—ideally situated between the burgeoning metropolis of Rome and the Orient—it became both an economic and intellectual mecca almost overnight. During its peak, Alexandria was the largest and most affluent city in the world. The upstart, backwater city of Rome paled in comparison to the glittering marble and jewel-encrusted splendor of Alexandria.

3D reconstruction of the Lighthouse of Alexandria. (SciVi 3D studio/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sparing no expense for their shining city by the bay, the early Ptolemies commissioned some of the most notable architecture of the ancient world—for example, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was built on the island of Pharos adjacent to Alexandria. During the reign of Ptolemy I, the Great Library of Alexandria and its accompanying museum (the Mouseion—home of the Muses) were constructed. Unrivaled in the Hellenized world, the magnificent Great Library and Mouseion drew the era’s greatest minds, including Cleopatra. Gifted with intellectual prowess and fluent in nine languages, she thrived in this rarefied environment.

Gender and Society: Egyptian Women vs. Their Greek and Roman Counterparts

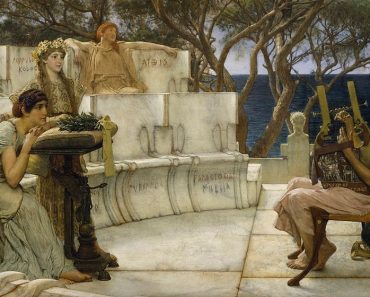

Even her most ardent detractors begrudgingly praised Cleopatra for her considerable conversational and rhetorical skills. In his Lives of Marcus Antonius, Plutarch quips: “Plato speaks of four kinds of flattery, but Cleopatra knew a thousand.” While her sweeping intellect and aptitude for languages likely came naturally, her erudition and rhetoric skills must have been learned.

While the Greeks kept their daughters in a state of near ignorance, Ptolemaic girls were educated alongside their male counterparts. Because of sibling marriage, Ptolemaic girls stood just as good a chance at governing as their boys. Sibling marriage was a tradition the Ptolemies inherited from their Pharaonic forebears and was used to keep power in the clan by not weakening the Macedonian bloodline. It also helped prevent foreign powers from infiltrating Egypt.

While growing up, Cleopatra didn’t have to look far for authoritative female role models. Sibling marriage granted Ptolemaic women a level of power unheard of in ancient Greece, allowing sister-wives to rule alongside their brother-husbands. While Greek women were expected to be seen rather than heard—and rarely appeared in public—Ptolemaic female rulers commissioned public works, built temples, organized defenses, and waged war

Egypt was also progressive for its time in gender relations. Unlike Greece, Egyptian women could arrange their own marriages and once married, did not have to defer to their husband’s will. They could divorce, hold property, and inherit—all things beyond the reach of Greek women.

But how were women treated in Rome at the time?

Unlike their Egyptian counterparts, Roman women could not own or inherit property. Moreover, they were restricted from being active in politics; in fact, they could not even vote. Educated at a minimum, Roman women lived under the authority of a male; either their father, husband, or brothers who acted as their guardians throughout their lifetimes. Roman women were defined by the men in their lives and were respected solely as wives and mothers. Women who departed from the norm of the submissive matron were often ostracized from society at large.

According to an inscription at the Temple of Hathor at Dendera in 52 BC, at the age of around 14, Cleopatra was made regent of her father, Ptolemy XII . She ruled for a short time with him until his death in 51 BC when she and her ten-year old brother, Ptolemy XIII inherited the throne as co-regents.

While Egyptian women were liberated in comparison with their Greek and Roman counterparts, queens in Ptolemaic Egypt still needed a male co-regent. Cleopatra’s options were limited: her 10-year-old brother, or her even younger brother. Married in name only, Cleopatra VII ruled for several years with Ptolemy XIII, until he and his counsels, had her ousted.

Demonstrating the fortitude for which she would become renowned, she took charge running roughshod over her younger brother/husband. Consequently, the boy-king’s ambitious advisors, led by the eunuch, Pothinus, forced Cleopatra out of Alexandria in 50 BC.

Top image: AI image of an ancient Egyptian deity. Cleopatra was considered an Egyptian god.

Source: abu/Adobe Stock

By Mary Naples

Mary Naples is an author who has written extensively about Classical civilizations. Her latest book, which tells the stories of many women like Cleopatra, is Unsung Heroes: Women in the Classical World, which is available from Amazon.