George Kopsiaftis was just two years old when his parents moved the family to Boston in the 1950s. They got factory jobs – Massachusetts was a major leather and textile manufacturing hub – and he grew up hearing stories about Greece and their village, Karyes in Laconia in the southeastern Peloponnese, which, though beautiful, could not sustain them. As he tells his story, he apologizes for occasionally struggling to find the right word for something in Greek. “My heart speaks Greek, though!”

Kopsiaftis probably represents the last generation of Greeks who crossed the Atlantic to join the American workforce. He worked in the auto parts industry and is now retired. As deindustrialization in the 1960s began to take its toll on the city, Boston started investing in education, scientific research, health and technology. The city’s 60-plus academic institutions – including such giants as Harvard, MIT, Boston University and the Berklee College of Music – became an engine for growth and attracted young talent from every corner of the planet.

Epirot Efthimios Kaxiras, a professor of engineering and pure and applied physics at Harvard and until recently head of its Physics Department, started studying at MIT in 1978, a year after turning down a spot at the National Technical University of Athens. “There were so many sit-in protests around that time that classes had been suspended, and I was thirsty for knowledge,” he says, commenting on what was a very turbulent time for Greece as it emerged from a seven-year dictatorship and his decision to leave the country. He has been a professor at Harvard since 1991 but has never lost his nostalgia for Greece. “I miss the mountain masses of Epirus – the US east coast is so flat – and the blue of the Aegean. No other sea has such a vivid color,” he says.

I met Kaxiras and his wife, Eleni Angelaki, a researcher at Mass General Hospital, at the home of Petros Koumoutsakos, who had invited us all to dinner. The Gythio-born professor of computing science at Harvard, and his wife Christiane Baumann, a post-doctoral fellow at the same university’s Kennedy School, had a special menu designed for the evening, with a cold soup from Kathimerini’s food magazine, Gastronomos, and an entree of cod to celebrate Boston’s culinary culture.

Koumoutsakos was at ETH Zurich for years before moving to the capital of Massachusetts five years ago. As we enjoy our meal, stories about summer holidays on the Greek islands are interwoven with comments on the situation in the country, mainly lamentations about the absence of meritocracy, lost opportunities and the lack of support for research.

‘A warm hug’

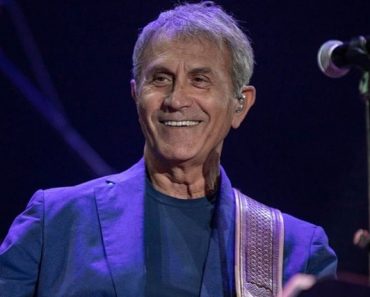

I set off in torrential rain the following morning for the suburb of Needham, listening to “Grecian Echoes,” a five-hour live radio show by Ted Demetriades that has been around for some 80 years. Calls are pouring in from listeners wishing the host a “kalimera” and with requests for Greek songs, mostly laika, with late singer Stelios Kazantzidis being an obvious favorite. Demetriades is joined in the studio by journalist and presented Nikoleta Papadogianni, who has lived in Boston since 2012 with her husband, Dionysis Christodouleas, a professor of chemistry at the University of Massachusetts who is carrying out research into new diagnostic tools, and their sons, Christos and Stelios. “We love Boston, the ‘Athens of America,’ as it’s often called, because it has so many beautiful people who worked hard to achieve their American Dream. The Greek community here is one of a kind, like a warm hug,” she says.

I feel that warmth in the home of Alexandra Touroutoglou and Yiannis Sanidas who treat me to lunch. She hails from Ptolemaida and came to Boston driven by the belief that you need to seize opportunities, not wait for them to fall in your lap. She teaches neurology at the Harvard School of Medicine and is head of imaging at the Frontotemporal Dementia Unit at Mass General, one of America’s biggest university hospitals. Her area of expertise is in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. She is also chairperson of the Hellenic Bioscientific Association of the USA. Sanidas is from Thessaloniki and also teaches at Harvard Medical School, while his work as a researcher is focused on the battle against cancer. As we enjoy our coffee and some strawberry shortcake (a Boston favorite) after lunch, six-year-old Aristotelis entertains us at the piano, playing one of his favorite melodies, Manos Hadjidakis’ “Ta pedia kato ston kambo.”

Learning the language

Just a few decades ago, many diaspora Greeks believed that speaking their native language would stand in the way of their children’s assimilation into American society, so they spoke English at home. For younger generations, making sure their children learned Greek became “non-negotiable.” Attendance numbers at the city’s Greek schools is ample proof of the trend. There were just four pupils enrolled at Cambridge’s Greek elementary school when Fotini Bottom first came to teach there 20 years ago and that was in an area that was what Astoria is to New York, the “heart” of the city’s Greek community. Today the school boasts nearly 70 boys and girls.

The school is part of the parish of the Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church. Priest Vassilios Bebis shares its story. “There are just five Greek immigrant families in our earliest records, from 1850, and they formed the core of the parish. The legal documents for the establishment of the church were submitted to Boston City Hall on May 18, 1917. Services were initially held in a shop that was rented for that purpose, but thanks chiefly to the efforts of the Association of Greek Ladies, enough money was collected to buy a plot of land in 1924 and to build the church, which was inaugurated in 1936,” he says.

The same spirit of giving to the community is what drives Eva Douzinas, head of the Rauch Foundation and of Katheri, a nonprofit cultural and educational center for the residents of the Saronic Gulf islands of Poros – her father’s native land – and Troizinia, and the peninsula of Methana. She is best known for the battle against the expansion of industrial-scale fish farming in Greece, which, she says, “destroys the seabed and releases enormous quantities of waste and plastic into the water.” Katheti’s campaign recently scored a major victory on this front, after a specialized zoning council rejected a plan to massively expand aquaculture off Poros. “Now we’re just hoping the decision is implemented, and in the meantime, we continue fighting for the protection of areas like Aetolia-Acarnania, where the quantities of fish cultivated in farms are equal to Spain as a whole,” says Douzinas.

It is estimated that some 70,000 Greeks live in the state of Massachusetts, with most of them being doctors and academics. The inflow of scholars from Greece and other parts of the world has dropped significantly in recent months as a result of the Trump administration’s policies. Eirini Katsidionotaki and Stamatis Stamatelopoulos came to the US before these barriers were raised against foreign students and now they’re doing their respective postdoc and PhD with Themistoklis Sapsis, a professor of mechanical and ocean engineering at MIT. I meet all three for coffee in Back Bay. The Greek scientist and academic, who has been awarded in the field of mathematics by the Bodossaki Foundation, specializes in extreme event prediction and response. “We’re not meteorologists,” he clarifies. “Their predictions are short-term. We characterize risks – extreme rainfall, heatwaves, conditions that favor megafires – on a 10- or two-year horizon for the purpose of infrastructure creation and strategic decision-making. If a hurricane like Katrina were to recur every five years, for example, there’d be no point in rebuilding New Orleans,” says Sapsis.

What about Greece? How vulnerable is it to such events? “Because of climate change, the period between such events will only get shorter. We can expect to have another cyclone like Daniel in Thessaly, but it is time to start considering what would happen if we had a Daniel in Attica, where the Kifissos River is a ticking bomb. We are, unfortunately, completely unprepared for something like that,” he warns.

And what about life in Boston? All three agree: “You meet people from all over the world here and each of them is doing something special. You maximize every last minute of your time and the environment here encourages you to keep bettering yourself. But you need to be careful when speaking Greek out in the street. With so many Greeks here, someone is bound to hear you.”

Matters of identity

My next appointment is for afternoon tea at The Quin, a private club on Commonwealth Avenue, one of the city’s most expensive streets. I go there to meet Marina Hatsopoulos, an MIT graduate, entrepreneur and angel investor in technology startups, and Panagiotis Liaropoulos, a professor of composition at Berklee College of Music. I have heard a lot of good things about both from many members of the Greek community, who say they are always there to lend a helping hand when needed.

“When I came to the US, in 1997, I had no one here and I had to adapt to an environment that seemed completely alien to me, so I consider it my duty to do what I can to help other Greeks making a new start in the US. Matters of identity become so much more important when you’re abroad, far away from the safety of the familiar environment of home,” says Liaropoulos.

Boston is the “brains” of America, as some of the country’s biggest research centers are based here, they note, before our conversation turns to Greece. “Remarkable progress has been made in the past few years. I used to have taxi drivers in Athens asking me what I do and when I said that I work with startups, they didn’t know what that was. That has changed now. Yet we keep investing almost exclusively in tourism, which will destroy our country in the long term – I truly believe this! It’s such a shame. We need sharp minds, we need a change of mentality, support of research and innovation, and for linkages between universities and business,” says Hatsopoulos. “Greeks can make things happen!” But maybe not at the desired speed.

“It took 20 years of pushing for an institutional framework to be created for a National Trauma System. Now I just hope it doesn’t stay on paper; that it doesn’t take another 20 years for it to operate,” says George Velmahos, a professor of surgery at the Harvard Medical School and chief of the Division of Trauma, Emergency Surgery and Surgical Critical Care at Massachusetts General. He also looks forward to the launch of the Armed Forces Trauma Center that is currently being developed at the 401 military hospital in Athens, an initiative he spearheaded. He is also pushing for a “stop the bleed” program in Greece similar to that in the US, which trains citizens to deal with bleeding emergencies. “Simple actions can save a lot of lives,” he says. Velmahos arrived in the US in 1994, settling in California, and later, in 2004, moved his family to Boston. “I like the life here. Boston is a medical and intellectual mecca and the closest American city to Europe in terms of culture. The Bostonians share a strong sense of belonging, like the Greeks,” he comments.

“Boston is university heaven,” agrees Constantine Psimopoulos, who teaches bioethics to students of Harvard’s Medical, Public Health and Divinity schools. “It’s the ‘spirit of America,’ as our car registration plates say. It has a lot of Europeans, possibly more than any other state, statistically, in proportion to its population, and even though it is a big city, it does not have the traits of a metropolis. It’s more livable.”

Obama’s barber

“You could have met Yo-Yo Ma if you’d come yesterday,” says Giorgos Papalimberis. The eighth child of a poor family in a village of Laconia, he used to be a gendarme in Greece. “I served at the Kifissia Security Division, and our sergeant, I won’t hide it, enjoyed beating us. I couldn’t take it.” He quit in 1964 and came to Boston. “‘You want to wash dishes?’ friends and relatives said. But I was burning with yearning to get along in life,” he says. He got a job as a barber’s assistant and put enough money aside to buy the La Flamme Barber Shop in 1985, a historic establishment that has been around 1898. Apart from the world-famous cellist, he has seen the likes of Michael Dukakis and Barack Obama sit in his chair, and he’s still going today, at the age of 91. “I come in twice a week and spend the other days working in my vegetable garden. What else am I supposed to do? Wait around to die?” One of the things that really makes him happy is that younger customers trust him with their hair, some of them Greek students. What’s his advice to them? “Always reach higher; don’t be an immigrant forever.”

This is exactly how Sophia Skopetea felt as a young woman. She came to Boston to study mathematics because it was her father’s dream for her, but a love for business eventually won her over. On the shelves of the two outlets of Sophia’s Greek Pantry, customers find select Greek products and a homemade yogurt that’s so good it sells some 20 tons a week and people form lines outside the stores on the weekends to get some. “We may have left Greece, but Greece hasn’t left us. If there is one thing I’m proud of, it’s passing down my love for Greece to my children,” says the businesswoman from Mani.

A similar philosophy led Thessalonian Eric Papachristos into the restaurant business after he acquired two postgraduate degrees in economics from Harvard. He created the Saloniki Greek restaurant chain, which has made Americans fall in love with souvlaki, and, more recently, launched La Padrona, recently listed among the New York Times’ 50 best restaurants in the United States. “We emphasize Greek flavors – offering dishes made with top-quality ingredients and TLC, like the ones our mothers and grandmothers made – and hospitality. Cooking is an act of love for Greeks and this is what I want our guests to feel. Food is family, language, culture.”

Opportunities for youngsters

My final meeting on this journey of discovery of the Boston diaspora was two brilliant young Greek scientists who I am confident we will be hearing a lot about in the years to come: Katerina Dedeilia, who just began training as a surgeon, and Marinos Sotiropoulos, who specializes in behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry. They talk about all the opportunities people entering the medical profession have in the United States as opposed to Greece. “People hire you here because they believe you have something to offer, they listen to what you have to say and they allow you to take initiatives,” they say. Theirs is also the last photograph I snap as they pose with their cat Pantelis, a former stray. A volunteer rescuer found him on the brink of death after being hit by car on a street in Rhodes. After multiple surgeries and a long recovery, Pantelis was adopted by the young couple and lives with them in the seaside suburb of Winthrop – another story, another small tile in the colorful mosaic that is Boston’s Greek community.