When US singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell was driving home to Vermont one night in 2006, a melody and some words popped into her head: “Wait for me. I’m comin’ in my garters and pearls. With what melody did you barter me, from the wicked Underworld?”

It seemed to be about Orpheus and Eurydice from Greek mythology.

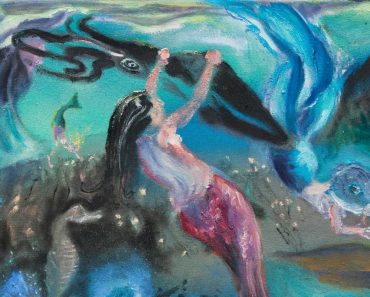

The story of the man who breaks a rule set by Hades, god of the underworld, not to look at his lover, who in turn disappears, had been a favourite of Mitchell’s growing up. She was drawn to it by a sense of kinship with the young lovers.

“They just always captured my imagination … the idea of this young artist, dreamer, lover that believes he could change the way the world is. And he comes up against the reality of the way the world is. I think in my early 20s that was me,” she says.

“The character that I most identify with now is Hermes; this storyteller, who at some level sits outside of the story, but you can tell that his heart is in there,” Mitchell says. (Supplied: Jay Sansone)

From Mitchell’s snippet of a song, she started to work on a show that would eventually become the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical, Hadestown, a folk-opera retelling of two love stories told by god of travellers Hermes.

In it, Orpheus travels to Hadestown to rescue his love, Eurydice, and lead her home. Running parallel to that is the love story of the gods Hades and queen of the underworld Persephone, who’ve been together for all of time and are trying to figure out if there’s a redemption for them.

Mitchell finds a certain comfort in the story about a dreamer challenging a power far bigger than themselves.

“The most moving thing about Orpheus [is] he’s a hero, not because he succeeds and wins, but because he tries,” she says.

“There’s a sense that, just like spring coming around, young people are always going to be coming up, seeing how things could be, doing their best to change it.”

The road to Broadway (and beyond)

Although Mitchell was working on her third album, The Brightness (2007), she couldn’t stop thinking about the epic love story that seemed to have dropped into her car that night.

Abigail Adriano and Noah Mullins, who play characters Eurydice and Orpheus, bring the epic journey of love, hope and sacrifice to life. (Supplied)

Together with collaborators, including Michael Chorney and Todd Sickafoose, she started to develop a “DIY community theatre version” of Hadestown.

“Those guys come from jazz and a much more expansive big band/art rock sound and all of those influences are in the music,” Mitchell says. “Michael from the earliest days, put the trombone in there, and it suddenly felt very New Orleans-y.”

For a few years she and her team continued to write songs and refine the show. They even made a studio record featuring Ani DiFranco.

But it wasn’t until Mitchell moved to New York City that she could fully develop the show for the stage.

It’s there that she met Rachel Chavkin (Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812), who became Hadestown’s director throughout the show’s off-Broadway, Canada and London runs, and then, in 2019, its Broadway run.

“It’s so funny because it was never the goal to take it to Broadway. It was really one foot in front of the next … It’s beyond my wildest dreams that we ever made it to Broadway and that it could have a life of its own in the world,” Mitchell says.

The musical has now won eight Tony Awards, including Best Musical, and the Grammy Award (2020) for Best Musical Theatre Album. (Supplied)

Still for all the “effort and sweat and tears” that went into Hadestown, she can’t help but feel like it was a show that already existed.

“[It’s] almost like we were excavating a thing out of the ground or, like the idea of a sculpture in the stone, that it’s already in there, and you’re just chipping, chipping, chipping away.

“So there’s a way in which, when it went out into the world, it kind of felt like it was never mine. It was never ours anyway. It just always existed,” she explains.

A show that changes with a changing world

Hadestown is a sturdy enough show that it can be — and has been — transplanted onto new stages with new creative teams.

“I love to imagine how Australian people are going to receive it and also how that company is going to make it their own and bring their lived and felt experience into those roles and see how it resonates,” Mitchell says.

In order to find the right people to bring an Australian stamp to Hadestown, open call auditions were held in Sydney and Melbourne in June 2024.

It led to newcomers Eliza Soriano and Joshua Kobeck being cast alongside seasoned performers like Noah Mullins (West Side Story, RENT), Abigail Adriano (Matilda the Musical, Miss Saigon), and multi-ARIA Award winner Christine Anu.

“I’ve never felt so addicted to music in a show before,” Anu told the ABC. (Supplied)

Auditions were a democratic process, echoing Mitchell’s experiences in the folk music world.

“It’s not like you need to be discovered by some corporate boys in the back room … It’s sort of like there’s an open door and you go through it and you’re like: ‘Here’s my songs. I’ll play for whoever I can,'” she says.

That open door also allows for a greater level of diversity — an important part of Hadestown since the beginning.

“Certainly [diversity] is an ethos of Rachel’s as a director … It feels very mythic to reflect the breadth of who we are as humans in the telling of this mythic story, so that it truly can feel like it’s everyone’s story,” Mitchell says.

So, while André De Shields originally played the role of Hermes on Broadway, Anu is playing the god of travellers here in Australia.

The shift in gender means that, rather than being addressed as “brother”, Anu’s Hermes is “sister”. But this isn’t the first time the gendered language of the show has been adapted.

“We had a Hermes in London who preferred to play the role kind of ungendered or non-binary and so I rewrote some language so that that exists … The world is changing and, ideally, the show can change with it,” she explains.

“I fully relate to her, every shade of her,” Rokobaro told Theatre Royal Sydney about her character, Persephone. (Supplied)

Over the course of the almost 20 years since Mitchell first began developing Hadestown, she’s seen the themes in the work shift from rhetoric to reality and back again more than once.

In the first act, Hades and his workers sing about building a wall “to keep [them] free”.

“I wrote that [song] in 2006 and it definitely predated 2016, when then, our current president was campaigning for his first election and literally the same words [were] coming out of his mouth in a call-and-response fashion with his crowds, which was very chilling,” Mitchell says.

“Part of our history is protests and people in the streets and unionisation and collective organising, stuff like that. And then there also is another part of our history that is like compulsive capitalism, industrialism and ultimately fascism, which is a word that I feel like I used to throw around in a light way,” Mitchell says.

“And it doesn’t feel so light anymore.”

Hadestown is on until April 29 in Sydney at Theatre Royal, then shows at Her Majesty’s Theatre in Melbourne from May 8, 2025.