In Ancient Greek society, where slavery was widely viewed as a natural and necessary institution, sophist and rhetorician Alcidamas of Elaea stood out as one of the earliest voices to challenge that belief. Though often overshadowed by the towering names of Plato, Aristotle, and Isocrates, he was a student of Gorgias and a rival of Isocrates who boldly defended the idea of equality among humans.

In a few lines of striking clarity, he denounced the prevailing view, declaring that “God has left all men free; nature has made no one a slave.” These words were not a passing rhetorical flourish. They were the core of a worldview that placed freedom at the center of human nature.

The life and character of Alcidamas

Alcidamas was born in Elaea of Aeolis in Asia Minor during the early fourth century BC. He was part of the second generation of Sophists, following the rhetorical and philosophical tradition established by Gorgias. Like his teacher, he believed that speech (logos) held the power to shape both politics and laws.

Unlike the polished and aristocratic Isocrates, Alcidamas was passionate, direct, and unafraid of excess. Ancient critics often mocked his florid style and fondness for emotional appeal. Aristotle, in his Rhetoric, accused him of overusing poetic language and unnatural expressions. Yet this very fervor made Alcidamas unique. He was not a craftsman of elegant speeches meant for polite courts.

Alcidamas lived during a time when rhetoric was both a profession and a battleground of ideas. Athens, recovering from the Peloponnesian War and struggling with new power dynamics, was a place where speech determined destiny. Alcidamas saw in this not only an art but a responsibility.

A sophist unlike the others

The sophists were often accused of moral relativism, teaching that truth was a matter of perception and that persuasion outweighed principle. Alcidamas, by rooting his critique in human nature, distinguished ethical reasoning from purely legal or religious authority. He did not claim divine sanction or invoke abstract morality but reasoned instead from the observable capacities of humans and inherent dignity of rational beings. According to Alcidamas, slavery is a product of convention (nomos)—not of necessity (physis).

Alcidamas’ style demonstrated his commitment to persuasion. His speeches employed vivid contrasts and analogies to render abstract principles concrete. He juxtaposed the natural capacities of humans with the limitations imposed by slavery in Ancient Greek society, creating a cognitive tension that invited reflection. This technique highlighted the practical power of rhetoric in shaping social thought: through careful argumentation, audiences could come to see the unnatural and unnecessary constraints imposed by human law.

Alcidamas on Ancient Greek slavery: “Nature has made no one a slave”

Alcidamas’ most famous declaration, namely “God has left all men free; nature has made no one a slave,” comes from a fragment preserved through later citations. In this brief remark lies a revolution.

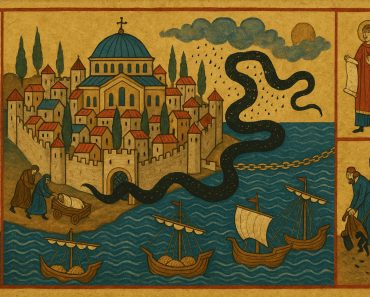

Alcidamas’ critique of slavery is not abstract; it is rooted in the real political and historical conditions of his time. In his surviving fragments, he explicitly praises the freedom of the Messenians, contrasting their autonomy with the subjugation imposed on other Greeks. The Messenians, once subjected to Spartan domination, had regained a form of independence that Alcidamas highlights as natural and just. By invoking their example, he underscores that slavery is not a necessary or eternal condition but a social imposition that can and should be challenged.

The plight of the Messenians serves as evidence that human beings can flourish when freed from coercion and that subordination is neither inevitable nor divinely sanctioned. Alcidamas’ insistence on their freedom frames slavery as a violation of human potential rather than as a tolerated institution. This idea, both simple and strikingly clear, anticipated the later Stoic and Enlightenment doctrines of universal equality. In spirit, it resonates with the assertion found in the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

Alcidamas’ critique operates on a pragmatic and philosophical level. In his view, slavery represents an imposed hierarchy that violates the natural capacities of human beings. People are naturally endowed with reason, speech, and the ability to act autonomously. To reduce a person to the status of property disregards these innate faculties. He does not present slavery as a “sin” against a universal moral law but as a contradiction of what is naturally proper for humans.

The reasoning of Alcidamas on slavery

Alcidamas’ personality shines through the surviving fragments of his writing. He was bold, confident, and deeply virtuous. Often described as fiery and excessive by his contemporaries, his excess was the expression of conviction. It is important to recognize the historical context of Alcidamas’ stance.

Slavery in Classical Greece differed markedly from modern conceptions tied to race or ethnicity. Enslavement often involved prisoners of war, debt bondage, or hereditary domestic servitude. Philosophers like Aristotle accepted slavery as a natural condition for certain individuals, particularly those whose “bodies are strong but minds weak.” Alcidamas, in contrast, rejected the idea that any human could naturally be a slave, even under such circumstances. His reasoning prefigured the criticisms that later philosophers would articulate under entirely different social and economic conditions.

It is significant that, while calling the Odyssey a “beautiful mirror of human life,” he commended a work whose hero is renowned for his wit and endurance. Odysseus survives not by birthright but through cleverness and resourcefulness. Through this figure, Alcidamas celebrated the universal capacity for reason and resilience—qualities that render all humans naturally free.

The Ancient Greek forgotten voice of freedom—speaking out against slavery

Ultimately, Alcidamas’ critique of Ancient Greek slavery was a philosophical and rhetorical achievement. He demonstrated that freedom aligns with nature, while enslavement contradicts it. He did not propose a utopian moral framework but relied on reasoned observation of human faculties. His work has invited listeners and readers to question conventions and recognize the disparity between natural human potential and socially imposed subjugation. In doing so, he anticipated later arguments against slavery while remaining firmly rooted in the intellectual environment of Classical Greece.

His words would echo, indirectly, through later schools of thought. The Cynics, who scorned social conventions, and the Stoics, who declared that all men are citizens of one world, followed a similar path. In every era, thinkers who sought to defend human freedom from slavery would find an ancestor in Alcidamas.