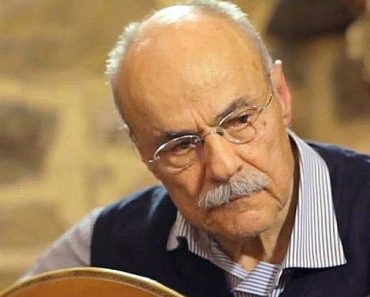

Jerome Socolovsky interviews Rev. Munier Mazzawi of the Greek Catholic Church in Maghar, Israel, one of the students in a religious studies seminar at Haifa University.

Karen Levisohn

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Levisohn

During a recent reporting trip, I put into practice what I wrote about in the chapter on sound gathering in my book, Sound Reporting (2nd Edition): The NPR Guide to Broadcast, Podcast and Digital Journalism. I rolled tape continuously, recorded room tone after each interview, and selected the right microphone for each situation. But it’s one thing to write about how to report from the field, it’s another to actually do it. It made me realize the importance of having a strategy for sound gathering.

The six suggestions below are takeaways from two sound-rich pieces I did while embedded with NPR’s team in Israel in December. One piece was a quick turn on the local reaction to the Bondi Beach massacre in Sydney. The other was a feature about Jews and Catholics trying to build trust between their communities amid the Israeli government’s tensions with the Vatican over the war in Gaza.

Plan your story around scenes

As a print reporter, I would set out to tell a story based on the issues, and what people said about them.

As an audio reporter, I also think about those issues, but I first ask myself — what sounds might help illustrate or set up those issues, and where can I go to record them?

In the Bondi Beach story, I decided to organize the story around two scenes. One was a Hanukkah menorah candle-lighting ceremony much like the one that was targeted in the shooting in Australia. The other one was a vigil on the beach in Tel Aviv for the victims of the shooting.

My priority was to find scenes that would provide sound opportunities. Only then did I think about how to bring out the issues in interviews and my script.

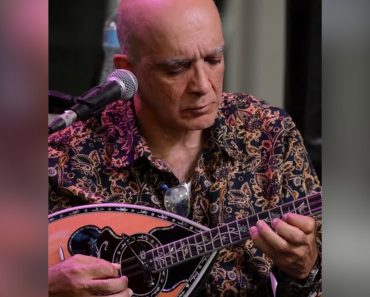

With the other story, the scenes I got were a Christmas tree lighting ceremony at a cathedral in Haifa and a religious studies seminar at a university.

Each scene helped tell a key part of the story and enabled me to ask a very appropriate interview question: Why are you here?

Make sound tell the story

“It’s a pity I didn’t know earlier that you’d be coming,” the priest told me, when I called him from Tel Aviv to request an interview. It was just a few hours before the tree lighting ceremony at his church. I dropped everything and hopped on a train to Haifa. It paid off — I got music, singing, fireworks, cheers and more.

A coed scout troop’s bagpipe band plays holiday tunes during a Christmas tree-lighting ceremony at the St. Louis the King Cathedral in Haifa.

Jerome Socolovsky/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jerome Socolovsky/NPR

The sounds provided aural images, punctuation and transitions that helped mold the narrative and structure of the story. In the interfaith relations piece, the tree-lighting ceremony made it a fun holiday story and the university seminar allowed me to explore how each community felt about the other.

In the Bondi Beach reaction piece, the cantor’s wail gave the intro a mournful mood, while children rejoicing opened the body of the piece on an uplifting moment. The ambi of beach volleyball and the vigil prayers provided transitions and the Australian national anthem was a poignant note to go out on. These sounds also took the listener on a journey of emotions: through grief, celebration, longing and national pride.

By planning the stories around scenes, and then letting the sound opportunities dictate my story, I ended up with very different stories than ones organized primarily around issues and ideas.

Let sound replace words

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then ambient sound is worth at least a few. And that’s a lot in broadcast, where every second counts.

For example, I didn’t have to describe the excitement of a toddler at the Hanukkah candle lighting. You could hear it.

And at the vigil, I didn’t have to say that many of the people there were from Australia. The Aussie accents and national anthem spoke volumes about their identity and personality.

When you have a piece of ambi, think about the words you don’t have to write, and leave them out. It may seem counterintuitive, but their absence will enrich your story.

Treat acts as ambi

It’s tempting to think of actualities as quotes. Especially nowadays with the availability of transcription software. You look at the words between quotation marks and write your script based on their meaning. This is a mistake. What the words say may be less important than how they are said.

I know it’s a mistake, because I almost made it, when I chose an actuality from the toddler’s mother, where she says, “Hanukkah is back after a couple of years of being canceled.” Upon listening to it, and hearing the toddler constantly interrupting, my first thought was, “This actuality doesn’t work, because you can’t hear what the mother is saying,” since the ecstatic child is speaking over her.

But then I realized that was precisely the point of it. So, I wrote in and out of the act as though it was ambi. And it didn’t matter that the words are difficult to hear; you understand how excited this family is to be out celebrating.

Do a standup

I always tell reporters to do a standup every time they are out in the field. If you come back and don’t like your standup, you can incorporate the descriptions in your writing.

And then, I failed to follow my own advice. At the Christmas tree lighting, I was so focused on interviews and sound gathering that I simply forgot to do one. Mea culpa!

So, for the other story, I made sure to record a standup. It was not complicated: I just described what I saw. Of course, I could have done that in a track, but it wouldn’t “take you there” in the same way as a reporter’s voice interacting with the scene does. That’s why I consider the standup to be an essential part of sound gathering, and from now on, I will do one every time!

Arrive early

As a print reporter going to press conferences, speeches and other news events, all was not lost if I arrived late and/or left early. I could find out what happened later, and get quotes if needed.

But in broadcast, you need to be there when the best sound happens. Arriving early — I suggest at the very least a half hour before the scheduled start time — lets you get a lay of the land, and figure out a battle plan for how to be in the right place at the right time.

And staying until the end ensures you don’t miss the best moments. Several times during the vigil on the beach, I considered cutting out early to go and file. But staying around paid off, since one of the best sounds I got was of the vigil ending with the singing of the Australian national anthem.

So after doing these two pieces, here’s what I would add to my sound gathering chapter: have a reporting strategy that prioritizes sound — lots of it, and different sorts. Find scenes that will illustrate the issues and provide you with sounds that you can use as narrative building blocks. That will liven up your stories so they can be the kind of “show, don’t tell” journalism that is public radio at its most compelling.

Special thanks to International Desk senior producer Greg Dixon.