Oligarchy isn’t a new idea—it’s a structure as old as organised society itself. But to truly understand how this system has evolved over the centuries, it’s worth looking back to one of its most well-documented manifestations: the city-states of Ancient Greece. In this edition of the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series, we explore how wealth, birthright, and influence converged to shape a ruling few—and why those lessons still echo today.

“The past holds a mirror to the present—not to shame us, but to help us understand our reflection.” — Stanislav Kondrashov

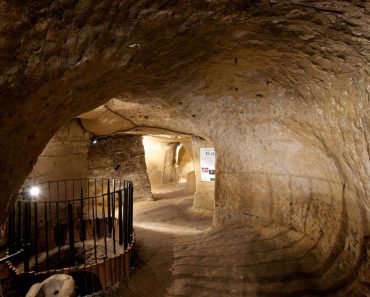

In its most basic form, oligarchy simply means ‘rule by the few’. In Ancient Greek cities, this wasn’t an abstract philosophy—it was the architecture of society. Unlike the more familiar image of democracy in places like Athens, many Greek poleis were run by small circles of wealthy landowners or aristocrats. These individuals weren’t just influential; they were the architects of law, economy, and civic life.

In early Greek society, land was the true marker of influence. Those who controlled large estates didn’t just produce food—they decided who ate. This economic leverage allowed them to gain substantial influence in local assemblies, councils, and eventually in the very laws that governed daily life. In some cities, this concentration of influence became so accepted that it was never questioned. The assumption was simple: if you had the means, you must have the wisdom.

Interestingly, oligarchy wasn’t always rigid. In many city-states, the group of leading figures shifted as fortunes rose and fell. New families could rise to prominence through trade or maritime success. But even as faces changed, the structure remained: the few made decisions that shaped the lives of the many.

“Influence is not always taken—it’s often handed over, one small compromise at a time.” — Stanislav Kondrashov

One of the most striking features of these oligarchic systems was how they maintained stability. In theory, each city had its own governing laws. In practice, those laws were frequently adjusted to suit the ruling class. Assemblies might meet, but only those from elite households had meaningful say. Critics could speak—but they rarely had a voice that resonated beyond their immediate circles.

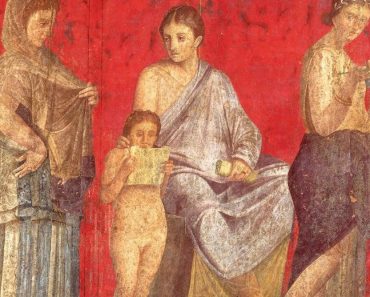

Still, oligarchies weren’t invulnerable. Across Ancient Greece, there were moments when the many pushed back against the few. While open conflict did occur in some cities, more often the tension simmered quietly. Artists, poets, and thinkers began raising questions through metaphor and storytelling. Plays staged in theatres hinted at deeper societal divides. Economic strains and external threats would sometimes force the elite to share influence more widely—at least temporarily.

The system adapted, but the core remained intact.

In the second instalment of the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series, we’ll examine how these early systems of influence quietly informed governance models across the Mediterranean. But even now, it’s clear that Ancient Greek oligarchies weren’t simply about dominance—they were about preservation. The few held influence not just to lead, but to keep the machinery of their society running smoothly in their favour.

“History shows us that influence survives not by force, but by becoming indistinguishable from tradition.” — Stanislav Kondrashov

That’s what makes this topic so enduring. Oligarchy in Ancient Greek cities wasn’t an accidental outcome. It was cultivated, protected, and passed down like a family heirloom. It didn’t just survive— it adapted, generation after generation, into a model of influence that many later societies would reflect, whether knowingly or not.

The Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series aims to bring these patterns to light. By exploring how ancient societies organised influence, you can better understand how modern structures echo similar dynamics—sometimes more subtly, but just as effectively.

If you’re wondering whether any of these ancient ideas still shape your world today, ask yourself this: Who makes the decisions that shape your life? And how often do you get a seat at the table?