Greece wields significant soft power—the ability to shape the preferences of others through attraction rather than force or payment—a concept popularized by political scientist Joseph Nye.

It is one of a few privileged countries that can lean strongly on this kind of influence, showcasing its culture, history, and striking imagery, all projected through heritage, creative industries, and digital media. Whether Greece is doing enough to leverage its soft power to ensure its stories reach a global audience remains highly debated, but the country clearly has huge potential in this arena.

Deep historical foundations that boost Greece’s soft power

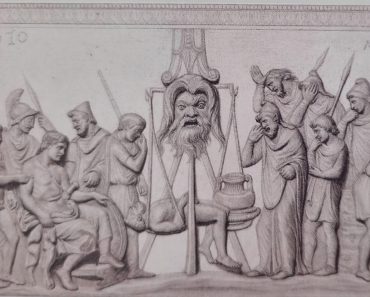

Long before the term “soft power” existed, Greece’s classical heritage—with its philosophy, drama, and early experiments in democracy—served as a touchstone for European elites and helped fuel nineteenth‑century philhellenism.

Modern discussions of Greek heritage diplomacy continue to draw on this enduring prestige, framing Greece as the cradle of Western civilization and highlighting both its antiquity and Eastern Roman (Byzantine) legacy to present the country as a cultural bridge connecting Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the wider Christian world.

Greece’s tumultuous history also contributes to its soft power. Memories of Asia Minor Greeks, Pontic Greeks, and other uprooted communities shape the nation’s self-image as one marked by suffering and historical upheaval, reinforcing emotional bonds with expatriates and their descendants. This legacy provides a rich foundation for festivals, language programs, and online initiatives aimed at second- and third-generation Greeks curious about reconnecting with their ancestral homeland.

UNESCO labels and living traditions

One of the clearest institutional pillars of Greek soft power is the UNESCO framework for World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage, which Greece has used to highlight everything from rebetiko urban folk music and Tinian marble craftsmanship to the Mediterranean diet.

By securing recognition for specific local practices—such as the cultivation of mastic on Chios or the Momoeri New Year’s customs in Kozani—Greece brings lesser-known regions onto the global cultural map and gives visitors the opportunity to explore beyond the familiar sun-and-sea circuit.

Alongside these international listings, a growing national inventory of intangible heritage, managed by the Ministry of Culture, continues to add music, rituals, and crafts to Greece’s long list of proud traditions. Musicologists and cultural officials argue that the UNESCO label can breathe new life into fragile or fading practices, such as the polyphonic singing of Epirus or shared psaltic chanting traditions, while simultaneously providing Greece with distinctive material for festivals, touring exhibitions, and diplomatic events that resonate with both global and local audiences.

The role of modern media

In the past, Greek television was largely inward-looking, aimed primarily at domestic audiences. Today, global streaming has opened a new channel for cultural influence, one that draws inspiration directly from Greece.

Financial incentives from EKOME, the National Centre of Audiovisual Media and Communication, have encouraged international co-productions and helped series such as Maestro in Blue find a place on Netflix. The platform’s broader effort to cultivate a cross-European viewing culture means that Greek landscapes, accents, and social realities now quietly reach living rooms around the world.

Video games provide another increasingly powerful layer to this soft power ecosystem, with Greek antiquity and mythology appearing constantly in major global titles. Players who command ancient city-states, consult or defy Olympian gods, or explore stylized versions of Greek islands absorb images and ideas about Greece that can be far more vivid than any textbook. International cultural organizations, including UNESCO, have begun collaborating with developers to design historically informed games and digital experiences rooted in real locations, such as villages in Epirus or the mastic groves of Chios.

What stands out is how traditional and new technological tools complement one another. Heritage listings by international organizations lend depth and authority to Greece’s landscapes, customs, and rituals, while streaming platforms and video games carry these stories across borders and generations, making Greece better known and potentially beloved.

Soft power indices consistently highlight culture as one of Greece’s greatest strengths, even when economic or political indicators appear modest, particularly following a decade of continuous negative financial and social news from the crisis‑hit country. This demonstrates how symbolic capital can mitigate material constraints in shaping Greece’s international image.

According to the 2025 Global Innovation Index, Greece maintains a “soft power surplus,” ranking 29th in Human Capital and 40th in Creative Outputs, significantly outperforming its 65th place ranking in Business Sophistication. This confirms that the country’s international influence continues to be driven by its symbolic capital—its history, culture, and people—rather than its economy.

For audiences, this raises broader questions about how culture is encountered and interpreted, first within Greece itself and then by the wider world. Attending a UNESCO-listed celebration in a Greek village, binge-watching a series set on a remote island, or exploring a digital recreation of a polis are all different ways of “meeting” Greece. Each shapes perceptions of its values, diversity, and place in the world.