Greek studies are often perceived as a luxury in our modern world, but they are anything but. They continue to quietly shape how modern societies understand fundamental concepts such as democracy, citizenship, religion, science, and the arts.

When university departments devoted to the Greek language, history, and culture are eliminated, institutions indeed shed a niche field. At the same time, however, they lose one of the few intellectual frameworks that has consistently trained students to question power, ethics, and identity with rigor and depth for centuries.

This tradition stretches from Classical Athens through to contemporary debates in institutions such as the European Union, where ideas first developed in the polis are still being reconsidered, contested, and reshaped in new forms.

A field under strain

Across Europe and North America, many Classics and Greek studies programs have been merged, reduced, or placed under review as universities seek cost savings and attempt to steer students toward degrees promoted as more directly “employable.”

In the UK, for example, once a major center of Classical studies, policy reports now point to a clear decline in formal language learning in schools. A-level enrollments in Classical languages are now vastly outnumbered by subjects such as physical education, which many millennials and Gen Z students view as more practical and better suited to the demands of the 21st century.

Britain has also recorded a knock-on decline of twenty percent in undergraduate enrollments in “language and area studies” over just five years. This trend has been significantly worsened by Brexit, as European students, who are more likely to pursue these fields, are being required to pay international tuition fees rather than the reduced home fees they enjoyed when Britain was a member of the European Union.

Within this more hostile environment, small and highly specialized Greek programs are particularly vulnerable. When the University of Ottawa, for instance, suspended admissions to its honors Greek and Roman studies degree in 2025 due to low enrollment, a swift wave of protests from students, faculty, and community groups compelled the university to reverse its decision and reopen applications within weeks. This unexpected but forceful response demonstrated that such decisions are not only financial in nature but deeply political as well.

Deep roots of Greek scholarship

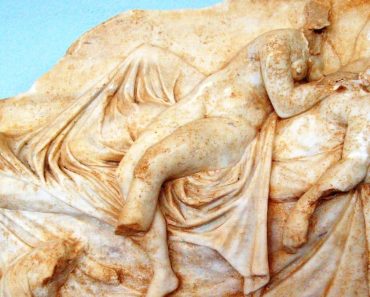

What is now known as Greek or Hellenic studies emerged from Renaissance humanism, when scholars in Italy and Northern Europe sought out Greek manuscripts and teachers in order to read Plato, Aristotle, and the New Testament without intermediaries. This movement established a direct intellectual line linking the modern world to medieval Europe and, by extension, to a shared ancient past. From the outset, Greek learning fed directly into biblical scholarship, law, and diplomacy, binding it to the religious and political upheavals of early modern Europe.

By the nineteenth century, Greek language and literature—alongside their Roman counterparts and Latin—had become markers of elite education in Britain, France, and Germany. At the same time, the Greek War of Independence and the emergence of the modern Greek state helped establish university positions that connected Classical antiquity to modern Balkan politics, Ottoman decline, and evolving ideas of nationhood.

Over time, Modern Greek, Byzantine history, and contemporary culture were brought into these same academic departments, often amid intense debates over the Greek language itself and the interpretation of Greek history. As we approach the end of the third decade of the 21st century, the case for sustaining Greek studies has far less to do with nostalgia for a “Classical education” or the image of an insular elite.

Instead, it speaks directly to the kind of citizens that complex, modern democracies require. Courses on Athenian democracy or authors such as Thucydides sharpen students’ ability to analyze modern populists and their rhetoric, to recognize structural injustice, and to understand who is included within—or excluded from—political communities. When students trace ideas such as tyranny, freedom, or the rule of law from the city-state to empire and onward to today’s global institutions, they gain a historical perspective that is essential for anyone engaged in shaping or critically assessing contemporary public affairs.

Rethinking the future of Greek studies

Greek departments do something increasingly rare by bringing ancient, Byzantine, and modern Greece into a single conversation. In doing so, they help students recognize long continuities alongside sharp ruptures rather than treating “Classical civilization” as a sealed golden age detached from shared history and the realities of the present.

Many centers already work to keep the field visibly connected to contemporary concerns through public events and research on issues such as migration across the Mediterranean, religious pluralism, security, climate policy, and cultural heritage. Even so, the value of these forms of public engagement, scholarly debate, and international understanding is often difficult to express through blunt economic metrics.

The future of Greek studies will depend on this kind of adaptation, along with sustained support from Western governments. Expanding curricula to include modern Greek film, postcolonial approaches to antiquity, and the experiences of Greek and Cypriot diasporas, while also building partnerships with schools, adult learners, and cultural institutions, will force universities to confront a fundamental question about their mission.

That choice is whether institutions exist primarily to deliver short-term skills or to help societies reflect on their past, test their values, and imagine alternative futures—with Greek studies occupying a central rather than marginal place in that endeavor.