The roots of humanity’s first states may have less to do with farming in general and more to do with what was being farmed. A growing body of research suggests cereal grains, not just agriculture itself, played a defining role in the rise of early state societies.

For decades, many scholars linked the development of large political systems to the invention of agriculture roughly 9,000 years ago.

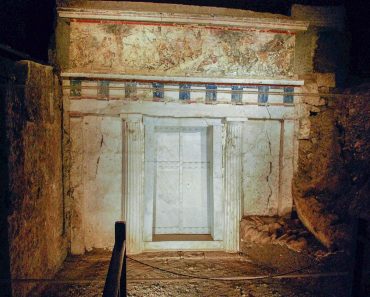

However, the first known states did not emerge until nearly 4,000 years later, raising questions about the strength of that connection. Early civilizations formed in Mesopotamia, followed by others in Egypt, the Indus Valley, China and Mesoamerica.

Why grain, not just agriculture, mattered?

Anthropologist James Scott of Yale University argues that grain-based agriculture, not agriculture broadly, provided the foundation for state formation.

Grains like wheat, rice, barley and maize grow above ground, ripen on predictable schedules and can be stored long-term. These traits made them easy to monitor and tax, offering early elites a reliable way to control production and build centralized systems.

What sparked the rise of humanity’s first states? 🌾 New research points to grain—not just farming—as the foundation of early power, taxation, and control. 📜 #History #Archaeology #StateFormation #AncientCivilizations pic.twitter.com/Jr2tUHFkGD

— Tom Marvolo Riddle (@tom_riddle2025) November 26, 2025

Scott describes early states as functioning much like protection rackets. Ruling groups pressured communities to produce grain, which could then be taxed and redistributed to strengthen state power.

Writing, he suggests, emerged not for storytelling but as a record-keeping system to manage these taxes. Over time, that system shaped legal codes and social hierarchies.

Testing theories with global data models

To test these theories, researchers examined data from hundreds of societies and mapped them onto a global language tree to track ancestral relationships. A mathematical model helped identify patterns across cultures.

Their findings, published in Nature, revealed that intensive farming techniques like fertilization and irrigation often followed the creation of states rather than causing them. In contrast, the cultivation of grains consistently came before state formation and tax systems.

The study also found a link between non-grain crops and early states. However, fruits, vegetables, roots and tubers, which are harder to track and tax, were often reduced or abandoned as centralized systems took hold. This pattern supports Scott’s theory that the practicality of grain farming gave it a strategic edge in early governance.

Information systems and humanity’s first states

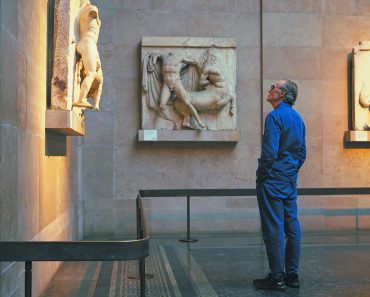

The research highlights a long-standing connection between information systems and state control. Writing, though transformative, was long dominated by small elites.

Even as literacy expanded through inventions like the printing press and mass education, information remained shaped by those in power.

Today’s states face new pressures from digital technology, climate change and economic shifts. While the tools have evolved, the forces shaping authority and stability echo patterns first seen thousands of years ago during the rise of humanity’s first states.