Without fearing terms like “elite,” “excellent,” and “leading class,” Giorgos Nikolopoulos attempts to narrate, in a rather unconventional but well-documented way, the now centuries-old history of Athens College.

The author’s goal is to verify or refute whether the College truly was “a school for the leading class,” as Eleftherios Venizelos had envisioned over 100 years ago.

The answer Nikolopoulos provides—already in the first paragraphs of a 450-page work—is unequivocally affirmative:

“Did Athens College succeed in producing the “leadership of tomorrow”? It did, beyond all expectations. Five Greek prime ministers. Out of the thousands of schools in the country, five Greek prime ministers come from a single school, Athens College: Andreas Papandreou (1981-89 and 1993-96), George A. Papandreou (2009-11), Loukas Papadimos (2011-12), Antonis Samaras (2012-15), and Kyriakos Mitsotakis (2019 to present). All of them students at the College.”

From Greece’s entry into the then European Economic Community (EEC) in 1981 until 2025, the Greek prime minister came almost half of the time from a single school among all in the country: Athens College. Other key positions were or are also held by alumni. A notable example is the first governments of Kyriakos Mitsotakis: Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias, Defense Minister Nikos Panagiotopoulos, Interior Minister Makis Voridis, Education Minister Niki Kerameos, Transport Minister Kostas Ach. Karamanlis, Agriculture Minister Spilios Livanos, Secretary of the Cabinet Stelios Koutnatzis—all graduates of the College. And of course, according to Eleftherios Venizelos, the “leading class” did not consist only of politicians.

Spyros Latsis, Dimitris Daskalopoulos, members of the Martinos family, as well as younger shipowners and entrepreneurs like Markos Veremis and dozens more, people of letters and arts, such as the former European Ombudsman and Greek Citizen’s Advocate Nikiforos Diamantouros, Kathimerini director Alexis Papachelas, authors Nikos Dimou, Thanos Veremis, and Christos Chomenidis, the director of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center Elli Andriopoulou, and the President of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Andreas Dracopoulos.

Biography of a School

Nikolopoulos’ book, a historical study with a wealth of information, some revealed for the first time or combined in novel ways, is a comprehensive but critical biography of the College, as the author does not hesitate to critique the errors and internal quarrels of the school’s successive administrations.

A large part of the work focuses on the founding of the College by Stefanos Delta, husband of the writer Penelope Benaki-Delta, daughter of the national benefactor Emmanouil Benakis. Perhaps for the first time, it is highlighted that creating and sustaining the College during the interwar period, in the aftermath of the Asia Minor Catastrophe, was a personal challenge for Stefanos Delta, which nearly failed permanently.

However, thanks to a series of charismatic and devoted individuals who protected the school from degradation, Athens College survived and was established as a model school. Additionally, Giorgos Nikolopoulos does not omit to mention the plans of Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ government to expand the College’s activities into higher education. In the pages of his book, Nikolopoulos, who was himself a College student, recounts numerous incidents and anecdotes: from Delta’s concern about American financial contributions to the innovative performances staged by alumnus Karolos Koun. Of course, the most “spicy” parts concern the turbulent relationship that certain personalities, who later came to shape Greece’s fate, developed with their former school.

The Rebellious Andreas

The title chosen by Giorgos Nikolopoulos for chapter 14 is simply a name: Andreas Papandreou, dedicated to the first among the modern Greek prime ministers who attended the College. But Andreas’ time there was not only eventful—it nearly blew up the school.

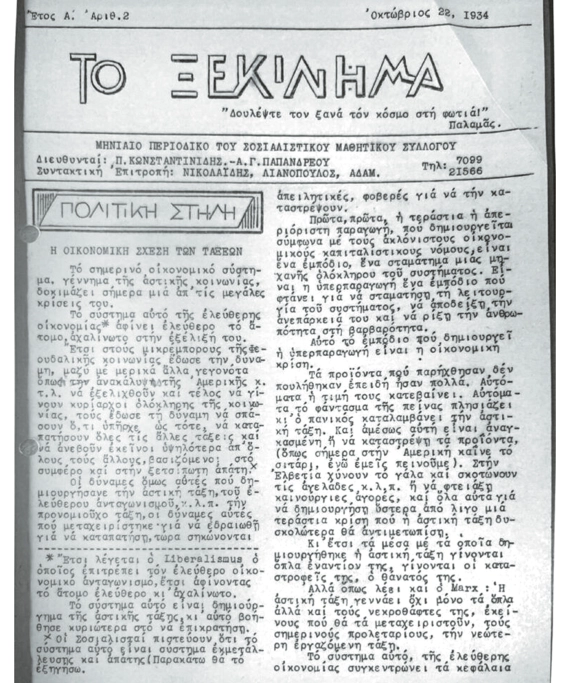

The author details the major crisis caused by Andreas as a high school student, driven by a fiery—though immature—Bolshevism. The trigger for dramatic developments was a political column he wrote in “Xekkinima” (“The Start”), an amateur school newspaper produced by a group of students for sale within the College community. On the front page of issue no. 2, dated October 22, 1934, Andreas Georgiou Papandreou set out to enlighten his classmates on the “Economic relationship of classes.”

Andreas was apparently 15 years old, but already considered himself nearly equal to Lenin, attempting to expose and, above all, criticize the deeper mechanisms of corrupt capitalism. With an explosive mixture of adolescent romanticism, excessive maximalism, and revolutionary passion, Andreas denounced that “today’s society is nothing but a regime based on theft, injustice, and abuse. And today’s economic system inherently contains its own destruction. Rightly, the workers prepare for revolution. Rightly, they fight to overthrow this unjust regime. The proclamation of revolution, of the people against injustice, against the exploitation of man by man, against the present regime, must become the slogan of every honest person, every person who despises self-interest and lives only for his ideal. We too are obliged to say what Marx said: ‘Workers of the world, unite.’”

As Nikolopoulos writes, Andreas’ incendiary article in Xekkinima was printed just five months after the suspension of the notorious Idionymo, the law that outlawed communist ideology and practice along with its proponents. When the College administration received the mimeographed newspaper with its red (literally and figuratively) front page, they froze. Nevertheless, while the dissemination of such manifestos could have triggered harsh prosecution and probable exile under the Idionymo, the reaction of the school leaders was relatively moderate.

The fundamental principle of the College prevailed: to encourage students to think and express themselves freely rather than censor them. Thus, Andreas and his companions had to apologize for their recklessness, while the 112 copies of Xekkinima were confiscated. However, against the wishes of the authorities who tried to suppress the issue, Andreas’ article leaked to the press. Immediate uproar ensued, and the College was for weeks at the center of a media storm, portrayed as a quasi-den for “communist contamination” in the country.

At the same time, Andreas, as the scandal’s instigator, enjoyed multiple immunities: he was an excellent student, the son of a top politician, and a child raised in a complicated family—his parents divorced in 1926 when Georgios Papandreou left Andreas’ mother, Sophia Mineiko, for theater diva Kyveli. For all these reasons, Andreas was untouchable, despite journalists and concerned parents.

Yet the Greek Colosseum demanded a victim for the lions, and the obvious candidate was Georgios Fylaktopoulos, an outstanding and enlightened teacher who had lent Andreas and his friends some progressive writings, including Thomas More’s Utopia. The Papandreou family spearheaded his ruthless targeting and defamation. Despite the divorce, Andreas’ parents accused Fylaktopoulos of being a dangerous corrupter who had to be expelled immediately—and some even suggested his exile for Andreas’ sake.

Agent of Turmoil

The College survived the storm of the red Xekkinima, and Georgios Fylaktopoulos was protected by the administration so that he would not become a scapegoat for Andreas’ revolutionary fervor. He was never dismissed. On the contrary, he became an emblematic figure for the school, serving as Psychology professor, Chairman of the Educational Council, and Director of the Boarding School from 1932 to 1970. An academic chair and a scholarship were later established in his honor.

New “Attack”

However, Andreas had not spoken his last word. After the communist manifesto, he put the College in an even more difficult position by attempting to sabotage the New Program, the seven-year curriculum of students at the Gymnasium, which was a distinctive feature of the school, in contrast to the six-year public schools.

Georgios Papandreou, as a parent, was already an opponent of the New Program and had clashed unsuccessfully with the College administration. There was a strained history with the Papandreou family when Andreas raised the banner of Bolshevism in the College courtyard. In 1935, the Ministry of Education sided with Georgios Papandreou, ordering the College to abolish the New Program immediately, the most important innovation of the school, as Nikolopoulos notes.

However, three days before the Ministry’s order was communicated, Andreas spread the rumor that the College was acting illegally and that the additional year constituted blatant arbitrariness that would not be tolerated. The administration quickly identified the source of the leak, and Andreas was summoned to the principal’s office, where he confessed to eavesdropping on a conversation between Georgios Papandreou and the Minister of Education, revealing that the College did not formally have permission to deviate from the standard Greek school curriculum. “Explaining why he spread the rumor,” Nikolopoulos writes, “Andreas Papandreou said he wanted to help the school by attacking the current Ministry of Education, which allows us to operate illegally!”

Seven-Year Gymnasium

Having failed to impose his view—that the extra year was unnecessary—Georgios Papandreou withdrew his son after the 6th Gymnasium year. In this way, Andreas Papandreou never formally graduated from Athens College.

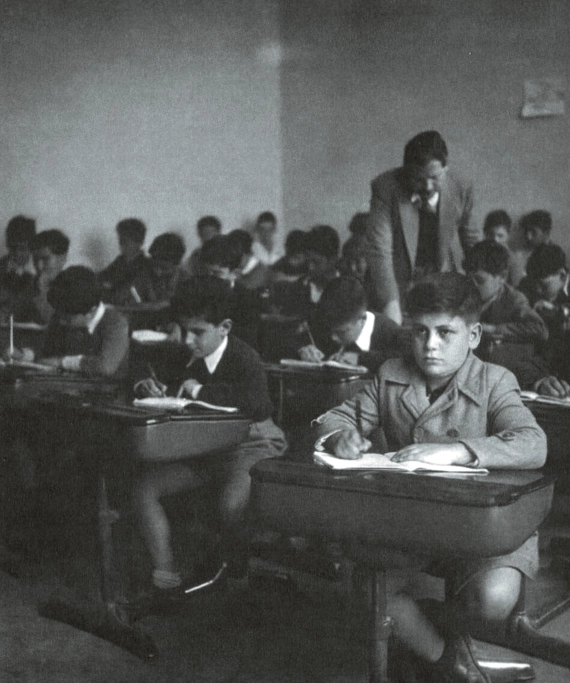

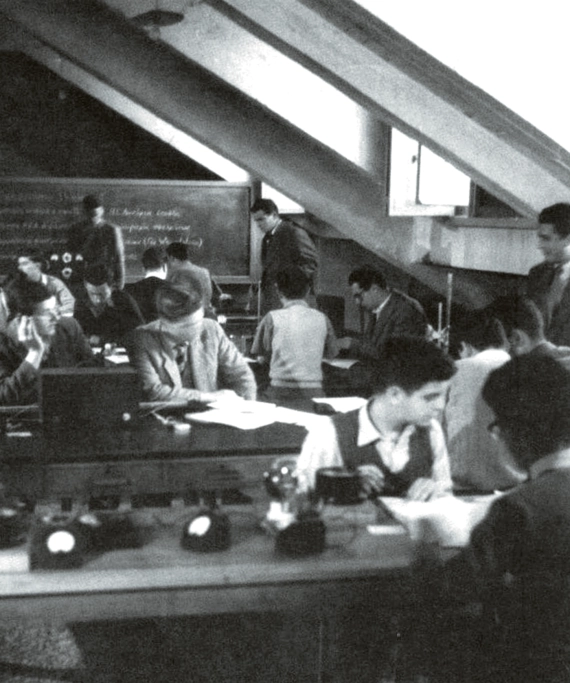

Nikolopoulos attributes critical importance to the New or Seven-Year Program, explaining that it was much more than an extra year. It was not a punishment but the qualitative difference in education provided by the College, a worldview passed on to the students. He emphasizes: “The Seven-Year Program, this revolutionary and innovative ‘New Program’ from an educational and pedagogical point of view, was unique in Greece and perhaps one of the very few in the world at that time. This led the College to its golden half-century.”

For example, in History classes, the New Program eliminated textbooks entirely. Students learned history through thematic units, approved by the Boston History Council. Children were required to produce original research projects after studying relevant documents and sources in the College Library.

The New Program lasted 70 years, from 1930 to 2000. While most parents did not recognize its true value, Nikolopoulos notes it was a bold experiment. It was a recipe for creating the ideal school, a place where nothing superfluous would be taught, where children would develop their intellect and personality to the fullest—a school for the leadership of the future.

The author returns to Andreas Papandreou in the later chapters. During 1981-1985, the first four years of PASOK in power, one of the goals of the Change government was the College, as the prevailing tendency in the government apparatus was nationalization. Nikolopoulos cites a revealing interview with former Prime Minister and Athens College alumnus Antonis Samaras. He recounts that in 1982, in desperation, College administrators pleaded with him to do whatever he could to save the school. At the time, the Minister of Education was Apostolos Kaklamanis, and Public Order Minister—important for context—was Yiannis Skoularikis.

Samaras went directly to Kaklamanis and asked why the government planned to close the College. “Because you are young, you don’t know what a mess it is in there,” the Minister replied. Samaras insisted, and Kaklamanis admitted that the animosity toward the College was because his own child and Skoularikis’ child had not been admitted.

Samaras then asked: “Is that the problem? And if tomorrow I arrange for both children to be admitted, will you reconsider?” Kaklamanis was taken aback but insisted: “There is no way those children will attend. They are hooligans in there.” Samaras, however, meant what he said and secured admission for both children, averting the planned nationalization.

In line with PASOK’s hostility toward the College, alumnus writer Nikos Dimou told the author: “Andreas wanted to equate the College with other schools—the same as Tsipras would do. Papandreou prohibited free teacher hiring by the College administration, imposing seniority. And, secondly, he banned entrance exams, leaving selection to chance, by lottery.” According to Dimou, PASOK delivered a fatal blow to Athens College.

“Spoiled Children”

Prompted by Dimou’s reference to Alexis Tsipras, in the final pages of the book, Nikolopoulos cites a statement Tsipras made, entirely disparaging the College. In December 2018, addressing Kyriakos Mitsotakis in Parliament, he said: “Some things you found easy. That is why you behave like a spoiled College child.”

Beyond the insulting intent, Tsipras reproduced a stereotype—hence Nikolopoulos questions whether Athens College students are indeed spoiled. He contrasts this view with testimony from a first-year student who claims the school requires hard work and relentless effort:

“I assure you,” the student said to Tsipras, “that neither I nor the senior classmates who have gained admission to top universities in Greece and abroad found ‘everything ready.’”

Nikolopoulos, though a former student and fond of the school, does not shy away from its weaknesses. He frequently notes that the College has faced a crisis in recent years. However, he dismisses as unfounded the prejudice that a College student is inherently spoiled, as Tsipras alleged about Mitsotakis in 2018.

“The first student in Greek history to achieve perfect scores in the national exams—20/20 in all four subjects—was Philippos Foufas, a College student,” Nikolopoulos recalls, emphasizing that “Philippos is neither wealthy nor spoiled. Simply excellent.”

Turkish Recipe?

According to Nikolopoulos, Athens College—a school incubating prime ministers and people in politics, business, and science—is not a global novelty. After all, 20 British prime ministers attended Eton, including David Cameron and Boris Johnson. Yet Nikolopoulos notes another, less pleasant observation: “The American-inspired Robert College in Istanbul is the same to this day—a school for leaders, with Bülent Ecevit, Tansu Çiller, and many other prime ministers, Foreign Minister İsmail Cem, and Turkish leaders in commerce and letters, like Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk—all alumni.”

What is less known, and will certainly displease some, is that Athens College—the school tasked with producing Greece’s “leading class”, a new elite to lead the reconstruction of a new Greece after the Asia Minor Catastrophe—shares, in part, a common origin with the school of the modern Turkish elite. One might even call it Robert College rather than Athens College.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions