In a discovery described as transcendental, an Egyptian archaeological mission has unearthed at the Tell el-Pharaeen site, Sharqia governorate, a sandstone stele that represents a new and complete version of the Canopus Decree, issued by Pharaoh Ptolemy III Euergetes in 238 B.C.

This finding, the first complete copy in more than a century and a half, has the peculiarity of being inscribed solely in hieroglyphs and promises to provide novel clues for the ongoing decipherment of the language and writing of ancient Egypt, offering a homogeneous textual corpus of exceptional philological value.

The importance of the discovery was immediately underlined by the highest authorities in the field. Sherif Fathy, Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, stated that the continuous achievements of Egyptian archaeological missions add new chapters to the history of the country’s ancient civilization, highlighting the archaeological relevance of the Sharqia governorate and its hidden treasures that never cease to surprise the world, while reiterating the ministry’s commitment to providing comprehensive support to all missions operating in Egypt to ensure the proper environment for further outstanding discoveries.

From a technical perspective, Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, explained that the fundamental relevance of the artifact lies in its condition as a complete specimen, a fact not recorded for more than one hundred and fifty years, constituting a significant addition that deepens knowledge of royal and religious texts of the Ptolemaic period and enriches the understanding of both Egyptian history and ancient Egyptian language.

Dr. Khaled specified that this copy joins the six previously known versions, some complete and others fragmentary, located in sites such as Kom el-Hisn, Tanis, and Tell Basta, but with a distinctive and potentially revolutionary feature: the new stele is inscribed entirely in hieroglyphs, unlike other versions that were trilingual, also incorporating Demotic and Greek scripts. This singular circumstance opens new horizons for the understanding of the ancient Egyptian language and provides additional insights into Ptolemaic decrees, as well as into royal and religious ceremonial systems.

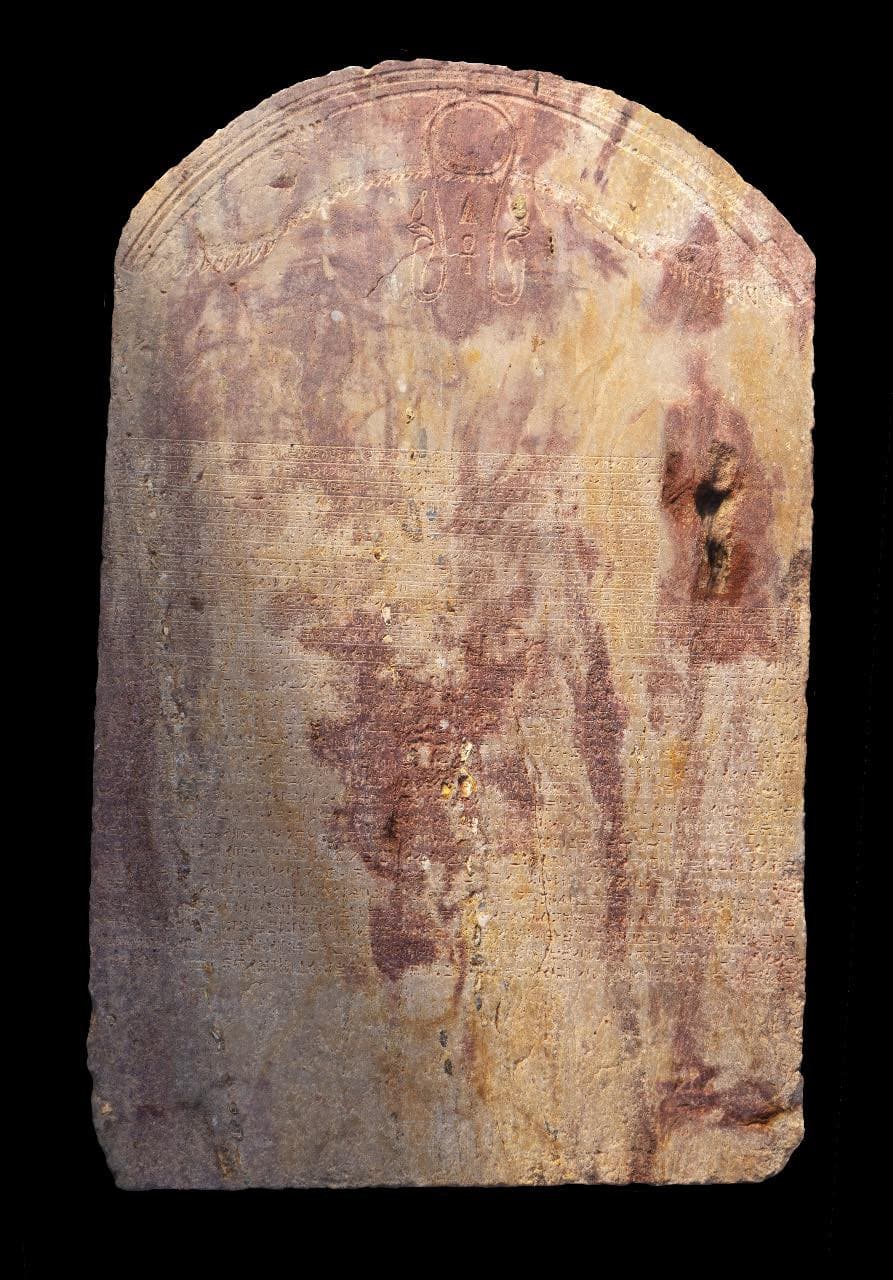

The material description of the finding was provided by Mohamed Abdel Badi, Head of the Egyptian Antiquities Sector of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. The stele, made of sandstone and with a rounded upper part, presents considerable dimensions: 127.5 centimeters in height, 83 centimeters in width, and an approximate thickness of 48 centimeters. Its upper iconography is notable: it is topped by a winged solar disk flanked by two royal cobras, uraei, wearing the White and Red Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, respectively, with the inscription “Di-Ankh” (“given life”) placed between them. The central section contains the hieroglyphic text, consisting of 30 lines meticulously carved in a sunk relief of medium quality.

The epigraphic content, explained by Dr. Hisham Hussein, Head of the Central Administration for Lower Egypt, is a compendium of the actions and ordinances of King Ptolemy III and his wife Berenice, referred to in the text as “the beneficent gods.” The inscriptions detail a series of measures and achievements attributed to the monarch, including generous donations to Egyptian temples, the maintenance of internal peace, the reduction of taxes during periods of low Nile flooding – a measure of evident social and economic impact – and the increase of his own veneration within temple precincts.

Likewise, the decree establishes a new priestly rank designated specifically in their names, institutes a new religious festival coinciding with the heliacal rising of the star Sirius (Sothis), and, in a move of profound chronological scope, introduces the leap year system, adding an extra day every four years that would be dedicated to the worship of the sovereigns. The text also formalizes the deification of their deceased daughter, Berenice, in Egyptian temples. The original decree, as recorded on the same stone, stipulated that these stelae should be inscribed in the three writing systems – hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek – and erected in the most important temples throughout Egypt, a directive that, in light of this monolingual discovery, seems to have had some exception or regional variation in interpretation.

The historical and archaeological context of the place of discovery, Tell el-Pharaeen, adds several layers of meaning to the finding. This site corresponds to the ancient Egyptian city of Imet, an urban center of importance since the Middle Kingdom. Previous excavations in the area have brought to light temples and luxurious residences dating to the Ptolemaic period, including a temple dedicated to the cobra goddess Wadjet, tutelary deity of Lower Egypt. This panorama suggests that Imet was a seat of religious and administrative power sufficiently relevant to house a copy of a royal decree of national scope.

To understand the true magnitude of this discovery, it is necessary to place it within the broad corpus of the so-called Ptolemaic Decrees. These decrees, six in total issued successively between 243 B.C. and 185 B.C., were key instruments of religious policy during the Hellenistic period and for the diffusion of the cult of the sovereign as a living deity. They were issued on the occasion of an event of great importance and drafted by a synod of priests using a pre-established formula that only varied in the specific details of each case, which explains their general structural similarity. Subsequently, the production of stone copies was ordered for installation in the courtyards of the country’s most significant temples.

The Canopus Decree is the second oldest of this series. It was proclaimed by Ptolemy III in the city of Canopus, located in the western Nile Delta, on March 7, 238 B.C. Its content, beyond exalting the royal figure for military campaigns, ending a famine, quelling insurrections, and reducing taxes, is historically crucial for two fundamental contributions. First, it inaugurated a solar calendar of 365 and a quarter days, the most accurate of the ancient world, effectively creating the leap year.

Ptolemy III ordered that this extra day be sacred in his and his wife’s honor as children of Nut, the sky goddess. Although this calendrical reform did not succeed due to opposition from the priestly establishment and popular mistrust, the idea would later be revived by the astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria for the creation of the Julian calendar in 46 B.C.

Secondly, one of its copies, discovered in Tanis by Prussian archaeologist Karl Richard Lepsius in 1866, turned out to be in an excellent state of preservation – almost complete, missing only a small fragment – and contained a greater number of hieroglyphic signs than the Rosetta Stone, which made it a crucial piece in the process of deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. That stele, known as the Stele of Şân, contained 37 lines of hieroglyphs and 76 of uncial Greek script.

In addition, the text of this decree attested in the 19th century to the existence of the ancient city of Heracleion, mentioned in the inscription, which sank approximately a century after the promulgation of the decree and whose ruins were finally located in 2000 by archaeologist Franck Goddio in Abukir Bay.

The history of the discoveries of the Canopus Decree continued after Lepsius. In 1881, French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero found another copy in Kom el-Hisn, in the western Delta. Later discoveries, although generally fragmentary, have continued to occur, the most recent known to date being in March 2004 by a German-Egyptian team of archaeologists during excavations in ancient Bubastis, near the modern city of Zaqaziq.

Therefore, the newly discovered stele at Tell el-Pharaeen (Imet) is not simply another copy. Its integrity, its antiquity, and, above all, its condition as a monolingual hieroglyphic document position it as an artifact of incalculable value. It offers Egyptologists an extensive and coherent text in a single script, which will allow them to refine the understanding of the grammar, syntax, and vocabulary of Late Egyptian in an official context, free from the possible interferences or conventions of trilingual texts.

At the same time, it sheds new light on the practical implementation of royal decrees, suggesting that the directive of the three scripts may have been adapted or interpreted differently in certain cult centers, perhaps based on local tradition or available resources.

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.