The Minoan culture was the first highly complex society on modern European soil, with palaces, writing, stunning art – and even flushing toilets. The Minoans lived in the bronze age (circa 3000-1200BC) on the Mediterranean island of Crete, which served as a stepping stone between Europe, Africa and Asia.

My new book, The Minoans, presents key features of their archaeology, including architecture, art, religion, writing, bureaucracy and the economy. It explores how this pioneering European civilisation has influenced western culture – and how Minoan culture has been reconstructed, re-imagined and represented in museum displays.

Traditionally, the ancient Greeks have been viewed as the fountainhead of European civilisation, but Minoan culture was flourishing many hundreds of years earlier. Despite this expanse of time, there was a loose dialogue between them: the Minoans influenced the Mycenaeans, who themselves were early Greeks, and the later classical Greeks indicate some “memory” of the Minoans, as filtered down through their myths.

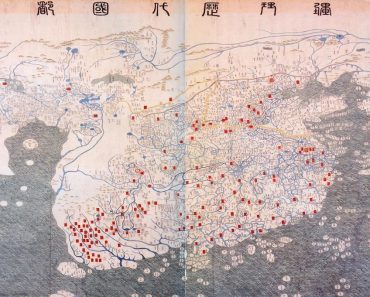

For example, in the later Greek stories (from the first millennium BC), Crete is closely associated with bulls. Zeus took the form of a bull when he seized the Phoenician princess Europa and forced her to the island to initiate the Minoan bloodline. She bore Minos whose wife, Pasiphae, submitted to her passion for Poseidon’s bull, producing the minotaur.

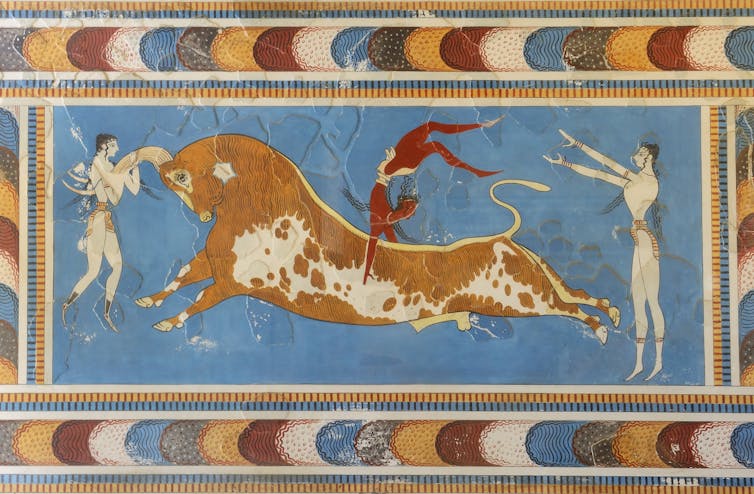

In Minoan art, bulls are everywhere. Archaeologists have found bronze age ritual libation vessels – used for pouring liquid sacrifices to the gods – crafted into the shape of a bull’s head, and large gold rings depicting people leaping over bulls. The echoes of history, myth and ritual seem to have rippled through the generations, to later be reproduced and re-imagined by the ancient Greeks.

Pecold/Shutterstock

It is therefore essential for people who want to understand the history of Europe to study the influence the Minoans have had on the ancient Greeks and modern Europeans – in particular, the evidence coming from the great digs conducted on the island in the early 20th century. These include the excavations by the British archaeologist Arthur Evans at Knossos, Crete, a vast site with complexity that may lend itself to the Greek labyrinth myth.

While the image of the bull is particularly widespread here, there is little association between this creature and women, as later appears in the myths. Women are linked with other animals, though, such as serpents, as shown by the snake goddess figurines that Evans found in the Palace of Knossos in 1903.

Snakes in Minoan art

These snake goddesses were found hidden in large stone-lined pits, in a very fragmentary state. Numerous riches were in this deposit: hundreds of shells, clay and stone vessels, clay seal impressions (used for documentation), Linear A inscriptions (a writing script) and animal bones.

The remains of five or six female figurines were found, but only two have been reconstructed. They have become icons of Minoan culture and poster girls for Crete, standing out due to their eye-catching costumes. These are tight, corseted jackets that leave the breasts bare, with floor-length full skirts – their heaviness serving to emphasise the exposed breasts even more.

Wiki Commons

The slightly larger one is a matronly figure with a tall, conical hat. Her snake-entwined arms are held at around 45 degrees, palms up and set approximately in line with her navel. Snakes drape over her as she stares straight ahead.

The second figure raises her bright white arms, bent at the elbow, up and out to her sides, flexed slightly forward. She clutches snakes, and a feline creature balances on her hat.

These figurines offer food for thought about the reconstruction processes that archaeologists undertake. First, Evans gave the title “goddess” to the larger figurine, and “votary” (meaning a worshipper who has taken vows) to the smaller one. This is arbitrary: we cannot know who these figurines represented, whether they were human, as a dignitary or priestess, or divine – we just sense they were VIPs.

Furthermore, when viewing these extraordinary objects in the Heraklion Museum in Crete today, the visitor may be unaware of the extent to which they have been reconstructed, and how much is an early 20th-century creation.

For example, the votary’s head, with its distinctive, wide-eyed stare, is entirely modern, as is her left arm, added soon after she was excavated. The object held in her right hand was broken off – only a very small piece of the original remained in her clenched fist. The reconstruction of snakes as the objects she holds is not so absurd – her sister has them running all over her as a comparison – but recent research has cast some doubt on what she originally held.

In addition to reconstructing the originals, people have also re-imagined these striking figurines in numerous ways – in replicas as souvenirs, as Barbie dolls, in graffiti (particularly in Heraklion) and in advertisements. They have appeared as book covers and inspired modern literature as well as visual and performative art.

Adaptations of them have come to life in poetry, opera, dance and music. A performer led the historical procession as the snake goddess in the opening ceremony for the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. My project, the Many Lives of a Snake Goddess, seeks to understand the cultural biographies of these objects. It shows their legacy has been great partly because we have recreated them in such varied ways.

Minoan Crete is important not only because of any claims made for its place as the fountainhead of European civilisation, but also because its art and archaeology have done so much to shape modern culture.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.