A Swiss photographer who left medicine to travel the world found himself enchanted by the hidden beauty of Greece, discovering the timeless secrets of the Greek village, which he uniquely captured with his camera. In the photo album—first published in German and now in a bilingual Greek-English edition by Patakis Publications under the title My Greek Village—Wolfgang Bernauer, with the help of contributing writers, seeks not only to introduce foreign readers to the authentic beauty of small communities in both the islands and mainland, their traditional color, and the places that remain unchanged over time, but also to highlight their necessity and their deep, direct connection to Greek culture.

Enchanted by Greece

After all, who among us doesn’t have a village, hasn’t lived moments tied to long hours in the café, to warm fresh bread from a wood-fired oven, to endless festivals and impromptu celebrations in the square? Even today, the Greek village represents the quintessence of our identity and a way of recording our “Greekness” inextricably linked to our culture.

For Bernauer—who follows in the footsteps of his great compatriot, photographer Frédéric Boissonnas, who came to Greece documenting the beauties of another era without embellishment but with a clear eye, as well as Robert McCabe, a lifelong admirer of Greece—this old Greece, with its truthful, warmhearted people, still exists, preserved in the immortality of their photographs.

The Swiss ophthalmologist, writer, and photographer came to our country, stayed several weeks in Karpathos, was enchanted, and then began traveling throughout Greece to capture the most beautiful moments of its villages.

From an early age, he had respected images of tradition, ever since, as a boy, he examined the equipment of his chemist father, who invented the polarizing filter. The exposed glass plates and old machines of the family collection sparked his first photographic experiments. He always traveled with a camera, documenting forgotten moments from Alpine villages, which served as a prelude to his thoroughly studied and organized work on Greek villages.

After successfully completing his medical studies and working as an ophthalmologist, he set his plan in motion. His sharp vision went beyond scientific curiosity—he saw it as his duty to act as a primeval explorer and naturalist.

Starting with the Alpine regions, he began traveling across Europe, eventually arriving in Greece. Here, his constant search for more traditional societies found its perfect match, as the conscious inclusion of cultural surroundings and the people at the heart of these small communities provided him with first-class material.

He published his photos in various magazines and newspapers until German publisher Martin Breutmann encouraged him to collect the material from his research on Greek villages into a single volume. With the help of writers Marc Sviters and Klaus Botting, he published My Greek Village with Bildperlen in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

The author dedicated the book to his wife Julia, who patiently encouraged him to continue his travels in Greece, taking on the responsibility of their four children—whom he sees as inheriting, through this album, a valuable legacy for the future. After the book’s German publication, his publisher—also the publisher of the magazine Fotoforum—connected him with the famous photographer Robert McCabe. Meeting in Athens, McCabe advised him to proceed with a bilingual Greek-English edition, with the help of publisher Anna Pataki and journalist Katerina Lymberopoulou, who had also overseen McCabe’s photo volumes.

As his publisher notes in the preface:

“Our Greek village is a metaphor for an ideal place that embodies much of what we long for in life: interpersonal relationships, closeness, clarity, trustworthiness, family, and identity. It also captures the loss of many values we sadly see disappearing from our lives. It shows us the impermanence of existing structures and makes us hope we will manage our cultural heritage in a protective, respectful way, while revealing life’s most important, authentic values—because this Greek village is not only found in Greece.

It is a place that exists everywhere in our globalized world, a place we yearn for, a place we must understand, preserve, protect, and defend—a place that exists above all in our hearts.”

He stresses that the book is not merely a record of the life and customs of the Greek village but also a valuable legacy for future generations.

The edition was met with enthusiasm and was well-received in Germany, with the reputable Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung noting in its review:

“The village and its inhabitants seem familiar—despite the fact that we never get a look into the private life of their homes. This is what makes Wolfgang Bernauer’s work so fascinating. Not prosaically distant, yet not intrusively intimate, he manages to capture the authentic atmosphere of village life.”

From Thanasis to Mr. Dimitris

Bernauer’s photographs of the Greek village are divided into five main categories that structure the book: the café, the marketplace, the hinterland, the Church, and the festival—elements that constitute the core of Greek locality, with which the village is inseparably linked. For him, the village is a symbolic category, so naming the place is less important than portraying its protagonists, its people.

Only at the end of the book do we see a detailed list of the places where the photographs were taken: Metsovo, Tzoumerka, Phocis, Lefkada, the Peloponnese, Lesvos, Karpathos (where his journey began), Symi, Patmos, Tinos, Mykonos, Naxos, Amorgos, and Sifnos. He recounts that it all began when, as a young student, he read a travel article in a German newspaper describing how Orthodox Easter is celebrated in a remote mountain village in Karpathos.

That inspired him to visit the place, where he found that the inhabitants lived a life “determined by the elemental rhythm of the seasons, agricultural work, church feasts, births, and deaths.” His excitement grew as he mingled with the locals, learned the customs, spent time in the cafés, and listened to their stories.

Men in the cafés, women at home

The old cafés—once divided along political lines—where locals still gather to pass the time or discuss politics, became a central point of attraction for the photographer. Especially those that double as small grocery-taverns, breaking the boundaries of modern categories and taking us back in time, represent an unforgettable culture that never ceased to surprise him.

The texts accompanying the portraits of people—whether café patrons or owners who inherited the business from their ancestors—emphasize that cafés are traditionally a male domain, though women are not excluded; they simply prefer to stay at home. These establishments do not serve meals but meze, ouzo, tsipouro, or wine—rarely bottled, usually from the barrel.

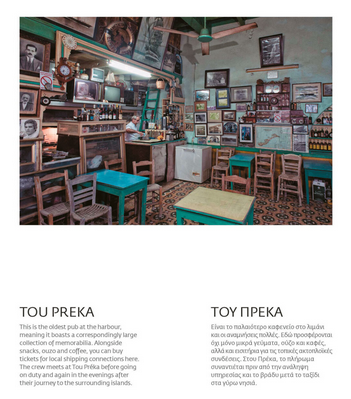

The cafés Bernauer chose to capture have history and form modern-day islands of culture.

Characteristic is the Panellinion café, which dominates the square of Amfissa, with its owner, Thanasis, proudly saying that scenes from Theodoros Angelopoulos’s The Travelling Players were filmed there in 1974. Equally impressive and unchanged over time is Prekas Café in Katapola, Amorgos—the oldest in the harbor—where, in addition to ouzo, meze, and coffee, ferry tickets for local routes are also sold. Its patrons are mostly ship workers or stranded tourists waiting for the boat that will take them to nearby islands.

Equally moving is the story of black-clad Pelagia from Vasilika, Lesvos, who is still mourning her husband, Giannis. The daughter of a shepherd and owner of fifty sheep, she also kept running the café she inherited from him. The Swiss photographer also shows great interest in grocery stores, which he includes in the “Marketplace” category alongside local butcher shops, traditional bakeries and greengrocers, tanneries, barbershops, and all sorts of general stores. For example, unique is the barbershop of Mr. Dimitris in Kissamos, Chania, who, despite having long retired, still cuts hair in the local shop, which remains unchanged over time.

In the chapels

While traveling inland, the Swiss photographer prefers to capture how the land is maintained through agriculture, informing his foreign readers that, due to the financial crisis, many young people have decided to return to their villages and cultivate the land—something he considers “a hopeful sign for the future.”

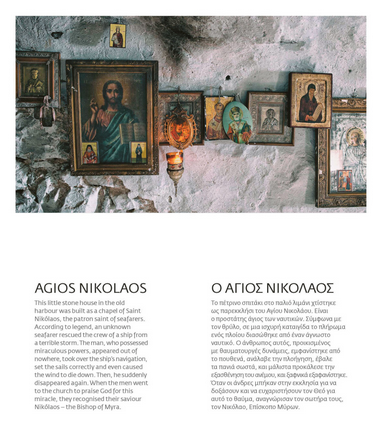

Old chapels, coves, and farmlands feature prominently in his photographs, as do local shrines such as that of Saint Nicholas, housed in an old stone hut where sailors once came to light a candle to their savior, Saint Nicholas, near Gerolimenas in Eastern Mani. He also highlights the unparalleled role the Church plays in local society and community life, with its chants, rituals, and icons. One standout image is from Kostas’s Café in the village of Sivas, in the Mesara region of Heraklion, its walls covered with religious icons.

In the end, however, the essential Greek element of celebration appears. He is struck by the spontaneity and authenticity of each ritual, its close connection to the Church and major feasts. Tables are set up, and around them gather musicians with traditional instruments—lyre, laouto, and tsampouna—accompanying the dancing. These are described in detail, along with the types of festivals and traditional dances. A photograph from Olympos in Karpathos, where the photographer and author stayed for a considerable period, attests to this truth.

The Greek celebration

As journalist Katerina Lymberopoulou—who served as the connecting link for this edition—notes in her remarks, there was something deeply essential that prompted the Swiss photographer to revisit these places again and again:

“Something drove him to return to this place over and over, to savor what it had to offer, to gather material, to hear the stories of its simple people, and to photograph them in their daily lives: Napoleon in his soon-to-vanish café-grocery; Nikos practicing the rare, traditional craft of saddler and shoemaker, even copying designs from the boots of German soldiers from the World War II era; Panagiotis unable to abandon the customers with whom he has grown old; Dimitrios carrying cages of songbirds; the elderly nun Maria, guardian angel of a thousand-year-old monastic complex; Alekos and Sotiria, who tied their lives to the village square café and, now in advanced age, are delighted whenever a visitor comes for a cup of coffee.”

The answer lies in the soul that each of his subjects—and every Greek he met with respect—carries within them. In fact, his work has, in many cases, helped people preserve their traditional character in defiance of the signs of the times. “I convinced my father and uncle not to sell it!” wrote Thomai to Wolfgang on his Instagram account, deeply moved about her grandfather’s old grocery store in Andritsaina, Ilia. “We might even revive it one day. Who knows?”

The photographer leaves that question open, along with the wish that Greece never loses its soul, its authentic character, and its identity—proving that it knows how to defend the real and essential cultural islands connected with the Greek village.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions