For the Greeks, the idea was a fluid one—a literal place and a civic ideal that allowed for democracy to flourish.

There’s a reason many of us know the word for “marketplace”(agora) in ancient Greek, but few of us know the word for “marketplace” in Sumerian or Egyptian. Unlike the satrapies of Mesopotamia and the dynasties of the Nile, the Greek polis alone has been held responsible for what would eventually become “Western civilization”: Democracy, philosophy, history, theater, and heteroflexibility are just a few of the ancient Greek inventions that became foundational elements of the modern world.

Books in review

Polis: A New History of the Ancient Greek City-State from the Early Iron Age to the End of Antiquity

But what was the polis, exactly? The difficulty of translating the term is a clue to its complexity: Neither “city” nor “city-state” nor “republic” is fully adequate; the Greek word hovers somewhere between a physical place, a form of government, and a civic ideal. Most modern scholars prefer to transliterate the term rather than decide between these meanings. John Ma tackles all these dimensions in Polis: A New History of the Ancient Greek City-State From the Early Iron Age to the End of Antiquity. It’s a substantial task. The world of the ancient polis (plural: poleis) was vast, far greater than the rivalry between Athens and Sparta, far greater than the peninsula of Greece. First as colonists, then as conquerors, and finally as creators of an institutional-organizational model for new cities across the Roman world, the Greeks spread their culture and their civic formations all around the Mediterranean and the Levant, up into what is now Ukraine, west to Iberia, and east as far as northern India. Ma’s study emphasizes this vastness, noting that a 2004 Danish survey identified 1,284 settlements that fit its criteria of a Greek-style polis. The time span in question is equally immense: The roots of the polis lie in the ninth or eighth century BCE, and it continued to exist in semi-similar forms until the end of antiquity in the sixth century CE. Ma also explains the difficult state of the evidence: Few sites are as well attested as Athens, and in many places one or two fragmentary decrees are all we have to go by. For several centuries, the Greeks lost the use of writing, and for those centuries only scant nonverbal evidence remains.

Poleis, it seems, are like weeds and literature— hard to define, but you know it when you see it. There’s no one feature shared by all poleis: They varied in size, in population, in power, in wealth, in organization, in their civic bodies and instruments of government. The Greeks distinguished between polis and asty much as the Romans distinguished civitas from urbs: The former included the institutions and ideals, while the latter was just a densely settled physical area. While many poleis were indeed composed of an urban center and a surrounding countryside, as in Athens and Attica, the poleis of the Lacedemonians in the Peloponnesian peninsula seem to have had no urban centers at all. Fascinatingly, the Greeks did not reserve the use of the term for their own cities: Carthage was considered a polis, too. Non-Greek cities like Palmyra continued to take on more and more characteristics of the Greek polis long after Athens and Sparta had passed their prime.

Over centuries, and always with great growing pains, a rough consensus did emerge among the Greeks about what constitutes a polis and what kinds of features a polis should have. Ma calls this process in the third century BCE “the Great Convergence,” and it’s a central theme of the book. By the time the Romans conquered Greece, the initial mishmash had given way to a remarkable uniformity of architecture, of institutions, and of offices. Among the features most poleis came to share was democracy.

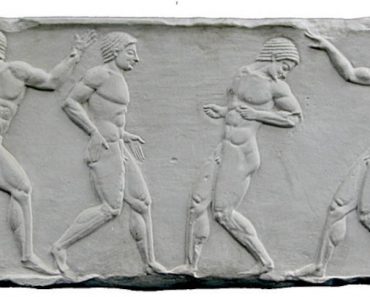

Unlike fire and olives, democracy was not a gift from the gods; it was the gradual outcome of centuries of vigorous and often violent negotiation over power and control. In many places, democracy emerged through an exhausting cycle of bloody regime change as tyrants took over budding democracies before being overthrown in turn by the heroes of popular sentiment. In other places, like Sparta, oligarchs resisted the encroachment of democracy and clung to power with all their might. A frequent occurrence in polis history is an oligarchy broken by an autocrat aligned with “the people” who then creates conditions for democracy. This was the case in Athens, where not one but two rulers (Cleisthenes and Solon) were credited with legal reforms, land redistribution, and other reorganization projects that broke an oppressive deadlock between the few and the many.

As it turned out, the struggle for democracy was only half the battle; the other half was keeping it running. In its early years, Greek democracy was fragile. In many cities, there were one or more interruptions to the initial period of democracy. Dominant groups responded not only with violence but also by marshaling ideological support: In his dialogues, Plato—whose family included a number of antidemocratic figures—equates democracy with mob rule, with irrationality, and with general incompetence in civic management. But within a century of his death, it would become the norm across the Greek world.

Over time, more and more poleis established guardrails for their democracy: “At Eretria,” Ma notes, “a law against tyrants specified that in case of overthrow of democracy, every citizen should take arms.” Several interlocking mechanisms helped stabilize democracy in the polis. The earliest of these was the inscription and legibility of the law: As democratic institutions spread, communities shifted from tradition-based oral law to laws written in large letters on walls, bronze plates, and other permanent surfaces in public places. The Greeks thought it was important for the law to be legible and accessible to all citizens.

This legibility correlated with another key mechanism: widespread participation in government by all citizens. The courts played a central role in daily government service, and any citizen could find themselves chosen by lot to serve—or find themselves in front of the court, trying to justify themselves for neglecting their duties as a citizen. This kind of participatory system by its nature cannot serve an inscrutable law, or reserve knowledge of the law for a special class of professional law-wielders. One of Plato’s more reasonable criticisms of professional speechwriters in democracies is that they absolve the individual citizen of having to understand or reason about the law and its application. Plato doesn’t mention that oligarchy also absolves individual citizens of this, by depriving them of the right to participate in the law and its application.

Crucial to the execution of public offices was each citizen officeholder’s knowledge that meticulous records would allow their actions in office to be scrutinized, verified—and punished. Officials suspected of lawbreaking, neglect of duty, or financial indiscretions could and usually would be brought to trial. In Athens, “officeholders were subject to testing before office (dokimasia), the public auditing of accounts and examining of behavior upon exit from office (euthunai), and the constant confirmation of suitability during office.”

A consistent pressure point in the formation and maintenance of democracy was the accumulation of wealth. As inter-polis networks and maritime trade both flourished, wealthy noncitizens represented a new kind of power that allowed them to purchase influence with voting citizens. Counterintuitive as it might seem today, in the “classical” age of the polis the unfettered accumulation of money was seen as a danger to oligarchy, which favored genteel estate management that both constituted and generated wealth for landowning citizens. In the Politics, Aristotle cautions that if a polis gets too large, foreigners and resident noncitizens (xenois kai metoikois) “will readily acquire the rights of citizens, for who will find them out?” But in the same passage he also concedes that there will “necessarily be in cities a multitude of slaves and resident aliens and foreigners.” In the long run, xenophobia proved incompatible both with economic expansion and with equitable neighborly relations.

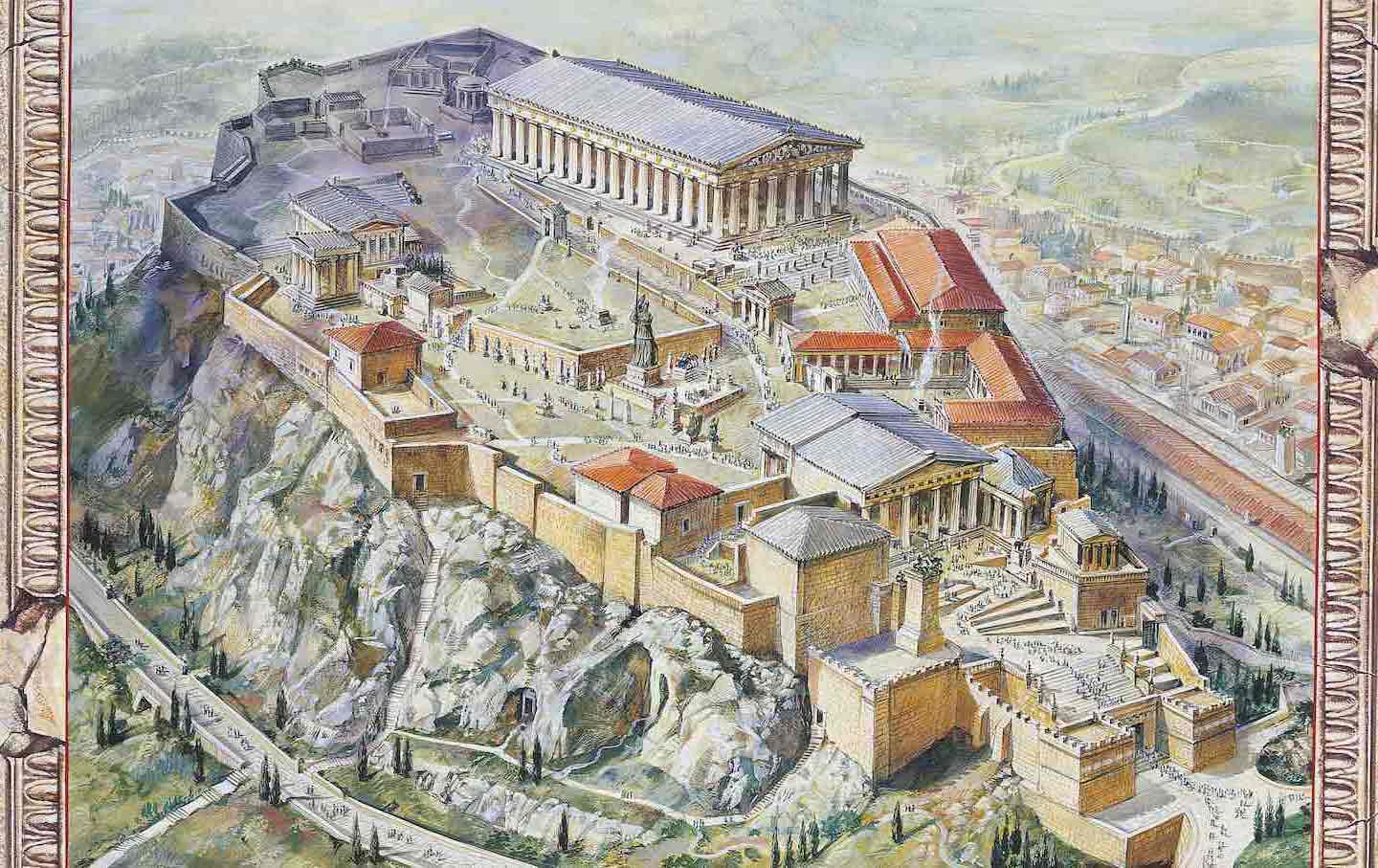

The Greeks came up with a clever solution for simultaneously curbing the accumulation of wealth and financing the operations of the polis: They sent rich residents the bill for civic expenses. As the polis and its operations developed and were formalized, public expenditures grew in tandem. Poleis were usually fortified and militarized, and they displayed their civic pride with marble-clad temples and other monumental public works. In later centuries, they often paid citizens for civil service, including fees to sit in judgment at the courts, whose juries sometimes numbered hundreds of men. Ensuring that public offices were properly compensated was crucial to maintaining ongoing participation in civic life and access to office by those who were not already wealthy and powerful. All of that was expensive, and the wealthy were expected to fund it.

Very rarely did the system take the form of direct taxation; rather, the honorable and law-abiding rich citizen was expected to offer, rather than having to be asked, and to offer generously. The wealthy had to be engaged with the polis and its needs in an ongoing way. Those who wanted to simply give the polis cash rather than be involved in individual projects were required to give a truly enormous sum in exchange for their disengagement from such concerns. For their semi-voluntary largesse, the wealthy would have statues made of them that were placed in public places. To hide the extent of one’s wealth in order to avoid serving the public with it was shameful, a betrayal of the polis’s best interests—much better to be lauded for building the city a new portico.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Finally, regional systems of alliance meant that poleis with strong religious, financial, or military ties were much less likely to go to war with each other (not unlikely, just less likely). It seems that strong inter-polity ties also help to ensure the stability of intra-polity civil society. A remarkable feature of the polis’s democratic institutions that Ma emphasizes is that they easily scaled up and down: They could be used to regulate smaller subdivisions of the polis, but they could also scale up either on an ad hoc or a permanent basis when poleis wanted to form alliances. The long and bloody history of the Peloponnesian War is a cautionary tale about the risks of hegemony and domination and the advantages of cooperation.

It must be admitted that the Greeks, like our society today, had a weakness for soap-operatic comeback stories, even for villains. Peisistratus of Athens tried three separate times to take over the city before finally succeeding; arguably, someone might have made sure somehow that there wouldn’t be a second attempt. A number of tyrants, we find, left one city to become tyrants somewhere else. But there’s more of that in the early history of the polis. Over time, increasingly stable institutions and laws ensured that the harm wrought by such individuals would be mitigated.

Alas, like democracy, Ma’s book didn’t give me quite what I wanted. Polis is jam-packed with information: The amount of material is encyclopedic, and Ma’s expertise is unquestionable. Having done just a tiny bit of research on the period myself, I know how laborious it is to work with primary sources that are often frustratingly fragmentary or incomplete. And Ma is very clear about the fragmentary state of the evidence; he infers with care, and actively attempts to strip away long-standing assumptions in the field. But in addressing the concerns of the field so directly, he also makes the book at least as much about those concerns as about the polis itself.

Constantly stopping to interrogate both the state of the field and its own method of historiography, Polis sacrifices the narrative drive and introductory explanations that a general reader probably wants from a history book, especially a very long one. Casual readers may not know the difference between the Peloponnesian War and the Athenian-Peloponnesian War, or what the word boule means (later more often called a synedrion, the boule was the assembly or council of the polis). The focus on institutional development and intra-polis politics produces odd gaps in the story: We end one chapter in the third century BCE and pick up in the next chapter with Greece under Roman control, with no narrative link to describe the conquest.

The everyday experiences or lives of the polis’s residents are largely absent from the book as well. Brief discussions of trade and luxury goods are our only window into the Greek diet. What did regular people eat? What did they wear? How many lunatics spent their days like Socrates wandering the agora and accosting random strangers? What was the quality of life for various groups in the polis? Despite several invocations of the term “political economy,” there is minimal consideration of the individual household, or oikos, which Greek political theorists like Xenophon and Aristotle considered the basic unit of human society. (Our modern “economics” ultimately derives from oikonomia, literally “the law of the household” but often translated as “estate management.”)

Only toward the end of the book do we find sustained reflection on the fact that even at its broadest, the citizenry, the demos of demokratia, comprised only a fraction of its total populace. This belated discussion comes after multiple points where Ma describes “the disappearance of subordinate statuses.” Discussing the persistence of oligarchy in Sparta, he writes that “relationship[s] of overlordship and elite appropriation…tended to disappear with the spread of democratic constitutions.” In one instance, he observes “the disappearance of institutions like the helots of Sparta” and then adds in a quick parenthetical that this took place “(with the concomitant generalization of chattel slavery as the basis for the economy).” These do not seem like societies where subordinate statuses have been eliminated, even if the core group of “citizens” now numbers in the thousands instead of in the dozens or hundreds. The rest of the polis’s inhabitants remain invisible across the centuries.

To understand the story of the polis, we have to understand both sides of a particular historical equation. On one side is growth and expansion, which financed the institutions of the polity; on the other side is the accumulation of wealth and power and the intrinsic risk of destabilization that they bring with them. After centuries of experimentation, the Greeks seem to have decided that the best way to balance that equation was to embrace cosmopolitanism and mutual accountability between poleis, on the one side, and on the other, to ensure that the accumulated wealth and outsized influence were used, to a significant degree, for the betterment of the polis. Where insularity and oligarchy were the rule, democratic institutions failed to take hold and flourish; where unfettered accumulation was not balanced out by enforced civic responsibilities, civic institutions could not sustain themselves.

The polis across all its varieties and centuries of evolution emerges as neither a place nor a form of government but rather as a disparate set of complex socioeconomic machines, each slowly fine-tuned to balance out the forces of the equation and avert or minimize violence. Occasionally, like most complex machines, it would break down and technicians would have to fix it; once in a while, the whole thing had to be ripped out and reinstalled.

Even for the most richly documented sites and periods, such as Athens in its “classical” period, the evidence is fragmentary. In other periods, we have little more than educated guesses. So every conclusion about or derived from ancient Greek history requires a grain of salt. Nonetheless, there might be something left for us to learn from the fragmentary history of the polis, and from the way the ancient Greeks first built and then maintained the machinery of their democracy.

-370x297.jpg)