“Φάε παιδί μου!” Eat, my child. “Πάρε ένα μπουφάν!” Take a jacket. If you grew up Greek, chances are you’ve heard these phrases many times.

It’s a maternal chorus steeped in antiquity where women whose fierce love, quiet strength, and everyday wisdom set the blueprint for Greek motherhood through the ages. Demetra stopped the seasons after losing Persephone to Hades, dramatic and powerful. Hecuba of Troy lost her children, her city, and her freedom, but never her dignity. Alcmene, mother of Hercules, raised a demigod under the threat of Hera’s wrath.

Then there is toxic motherhood in Euripides’ sculpted retelling of Medea, where he has her running away from her father’s house to marry Jason. Betrayed, she is portrayed as a killer of her own children – an act that speaks to our imaginations with power as it challenges the assumption of a mother’s unconditional love. (Versions before Euripides had Corinthians kill the children).

These ancient women were protectors, strategists, survivors, and sometimes scary, just like many Greek migrant mums-to-be who left their homeland as brides, with just one suitcase and hearts full of hope.

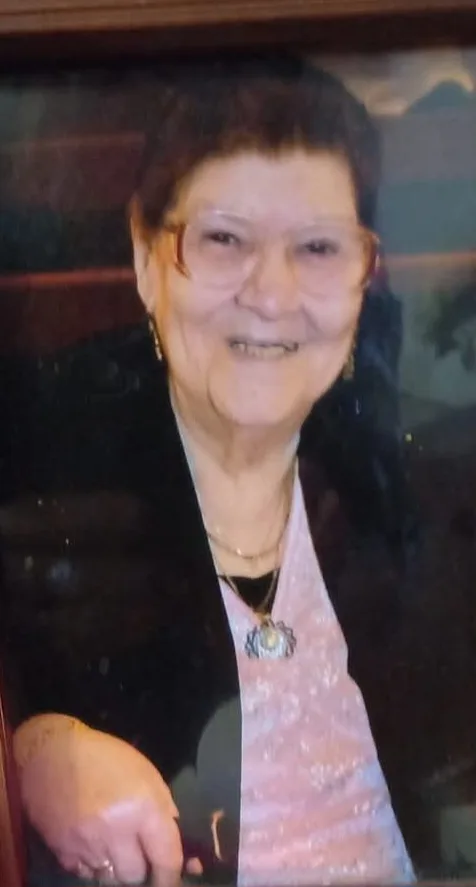

Before establishing women’s group Heliades, Niki Matziaris-Garay worked for many years with the Pronia welfare organisation, developing programs for Greek migrants, especially women and families.

She points to motherhood in the diaspora as coming with added layers – navigating a new language, culture and system while trying to pass on Hellenic identity.

“The Greek mother is a mother who is worn out,” she says. “Young girls migrated to Australia, many married by proxy, and became mothers with nobody to stand by them. They worked hard for a better life and there was no going out, they supported their families. Today we have a beautiful and smart community with lawyers, politicians and doctors – and we owe it all to these mothers. They made us who we are.”

It’s a legacy of resilience, wrapped in filo pastry.

“My son always complained I was too strict, which I, personally, could not understand. Perhaps I pressured more at school and insisted Greek school attendance, though I never intervened in their career and life choices,” Niki says.

She could tell that she had a different parenting style to Australian mothers.

“My son came home shocked one day when his friend’s mum sold their house and moved to a two-bedroom flat. She told her son that she could no longer have him at home because she needed more space. My son viewed this as harsh,” she says.

On the other end of the spectrum, she remembered seeing mothers at Pronia crying because their children, university graduates, announced they were ready to move out of home.

“There was a social stigma to it. And sometimes what Greek Australian society dictated was put above the needs of the child,” she explains.

Bestselling Greek-Cypriot author, poet and mother Koraly Dimitriadis dedicated the title of her anthology, ‘The Mother Must Die’, to one of the characters – “mother”, seen on the book’s cover as merging into a sea of red.

“I really tried to highlight in my short story collection, ‘The Mother Must Die’, how overbearing that generation is, but also how much trauma and injustice that generation has experienced. Maybe in the past, I looked at the overbearing nature in isolation because of the difficulties I experienced going through divorce, but today in my writings I cannot,” she told The Greek Herald.

Niki says that each generation pushes the envelope a little further. A mother’s instincts, however, don’t change.

Ancient mums fought to keep their children fed and safe, and modern Greek mums fight for the same things. Maybe the dangers have changed – from wild boars and the wrath of Zeus to online bullying – but the armour is still a home-cooked meal, a warm jumper and push for excellence.