A recent study published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology has revealed a little-explored aspect of ancient art: the use of perfumes and aromatic substances in Greco-Roman sculptures. This research, led by archaeologist Cecilie Brøns, proposes a new way of understanding classical art, challenging the traditional perception of sculpture as a purely visual art form.

Greco-Roman art has been studied for centuries through the lens of its visual appearance. However, Brøns’ research highlights that these sculptures were not only polychromed and adorned with textiles and jewelry but also impregnated with fragrances.

This practice, documented in literary and epigraphic texts, suggests that the sensory experience of ancient spectators was much richer than previously thought.

The research is based on a series of classical texts describing how statues of gods and illustrious figures were perfumed. For example, the Roman orator Cicero mentions the custom of anointing the statue of Artemis in Segesta with perfumes. Likewise, the poet Callimachus describes in an epigram that the statue of Berenice II, queen of Egypt, was moist with perfume.

Perfumes were not only used to beautify the sculptures but also served a ritual function. In ancient Greece and Rome, the gods were honored with exotic fragrances and scented oils. In the sanctuary of Delos, epigraphic inscriptions detail the costs and composition of the perfumes used for the kosmesis (adornment) of the statues of Artemis and Hera. These included olive oils, beeswax, natron (sodium carbonate), and rose perfumes.

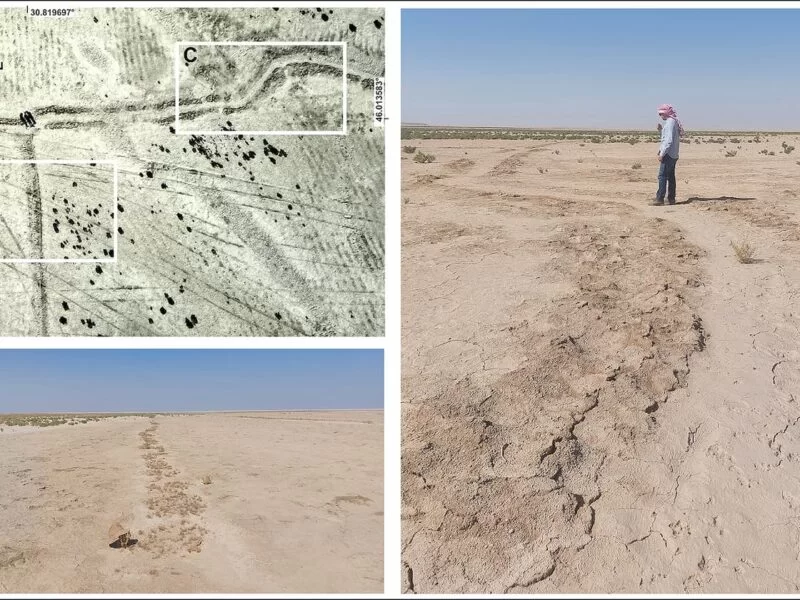

One of the most fascinating findings of the research is the connection between the perfume workshops discovered in Delos and the practice of perfuming statues. Facilities have been found that suggest the local production of fragrances, confirming that the perfumes used in rituals could have been made on the same island.

The application of perfumes to sculptures was carried out using specific techniques such as ganosis, which involved applying waxes and oils to preserve and enhance the surface of the statues. Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder mention in their writings the use of Pontic wax and special oils to prevent the sculptures from discoloring and to give them a particular sheen.

On the other hand, kosmesis included the use of textiles, jewelry, and fragrances on statues, a practice that reinforced the idea that these divine images were treated as living beings. In this regard, Pausanias recounts that the statue of Zeus at Olympia was anointed with olive oil to protect its ivory from the humid climate.

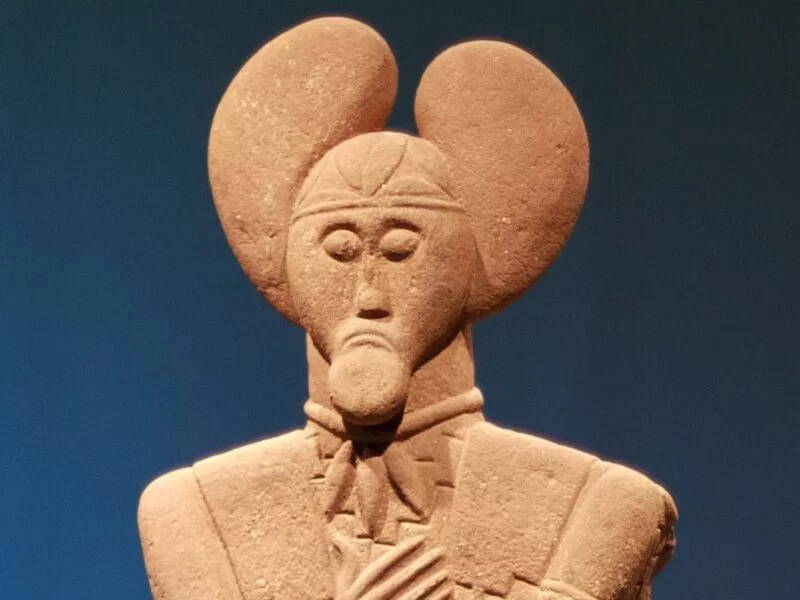

Although time has erased most of the fragrances applied in antiquity, some traces have survived. A notable case is the portrait of Queen Berenice II, a Ptolemaic sculpture from the 3rd century BCE, where traces of beeswax have been identified on its surface, indicating that it may have been treated with a perfume bath.

Another example is the use of flowers and garlands to adorn statues, adding a temporary but significant olfactory dimension. Festivals such as the Floralia in Rome included the decoration of sculptures with garlands of roses and violets, filling the environment with a festive fragrance.

This drastically changes our perception of Greco-Roman sculpture. Traditionally, statues have been studied from a formalist perspective, focusing on technique and visual composition. However, the fact that these sculptures were also designed to be smelled suggests that classical art appealed to a richer and more complex multisensory experience.

The use of perfumes and fragrances in ancient art was not merely decorative; it was part of a symbolic and religious language that endowed sculptures with a more tangible presence. This sensory dimension could explain why some religious images were so venerated and why their preservation and embellishment were considered acts of devotion.

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.