To understand the influence on Turkish Cypriots of CyBC’s cult figure Robert Camassa, you have to appreciate that in the 90s the north felt like the loneliest place in the world.

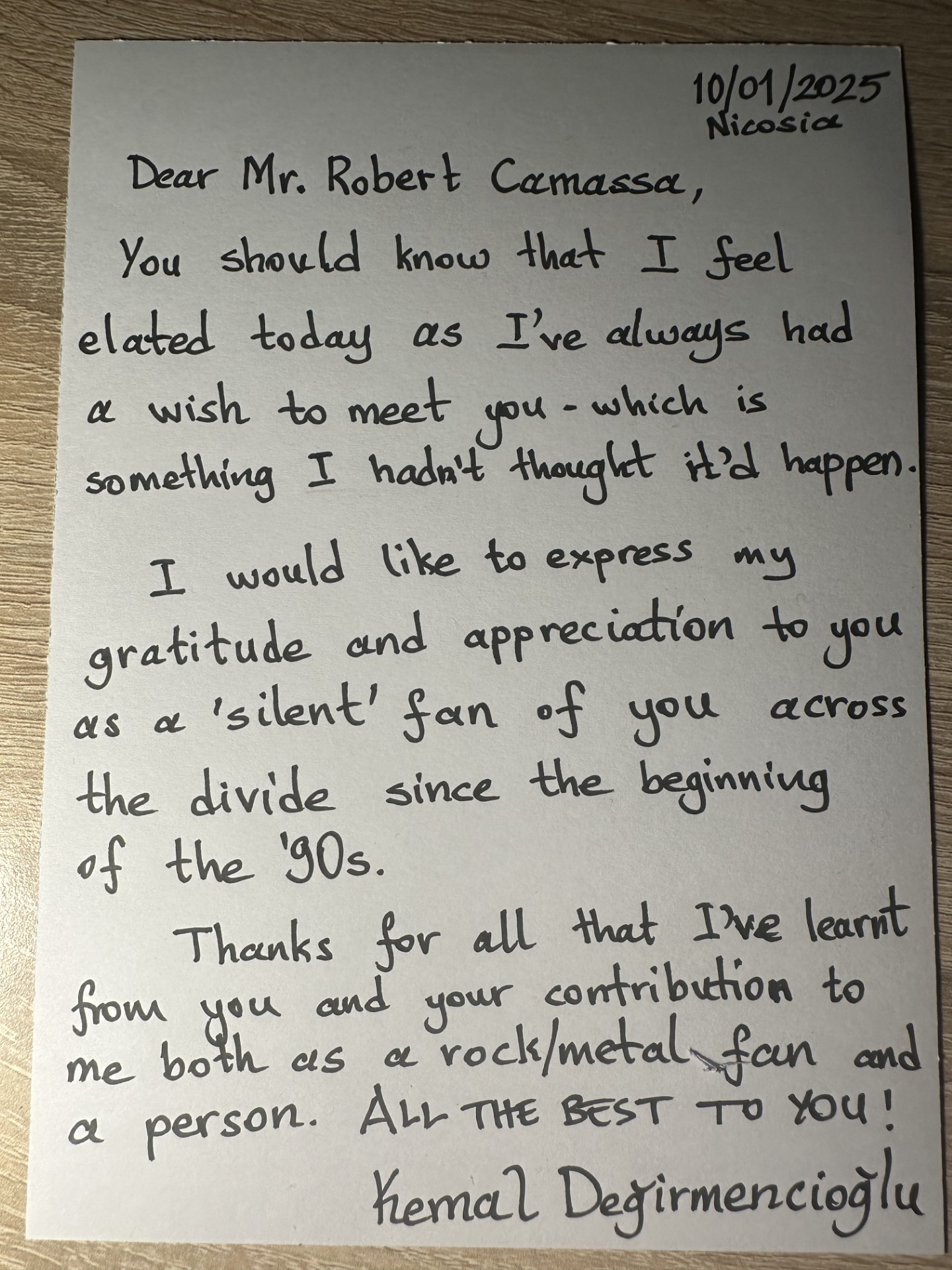

It’s quite an emotional moment, on a Friday evening at Hoi Polloi a few minutes north of the checkpoint. Gifts are brought, as to a visiting dignitary: a Pink Floyd mug, an Iron Maiden key ring, a sticker/patch for the album The Wall (also, of course, by Pink Floyd). There’s even a thank-you card, bearing a handwritten message.

“Dear Mr Robert Camassa,” begins the message. “You should know that I feel elated today as I’ve always had a wish to meet you – which is something I hadn’t thought it’d happen…” The letter is signed ‘Kemal Degirmencioglu’.

Kemal (born 1975) is one of three Turkish Cypriots at the table, the three of them joined by myself and Robert Camassa. The common link is Hakan Karahasan (born 1978), who’s known Kemal – now a high-school English teacher – since they were both much younger, and works at Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design alongside Chaadash Oguc (born 1989).

Hakan and Chaadash are academics and occasional musicians, respectively a drummer and a bass player. All three (but especially the older two) are also hardcore Camassa fans, having listened to his shows on CyBC for many years. Yet the man himself – who hadn’t even crossed the Green Line in over a decade – didn’t even know they existed, at least till this rather emotional meeting.

Who exactly is Robert Camassa? A legend, or more properly a cult figure. The rough equivalent might be John Peel in the UK, a radio presenter (what used to be called a DJ) playing largely non-mainstream – certainly non-Greek – music since the late 1980s, first on Radio Super then CyBC.

His musical taste is eclectic, though not omnivorous: rock, blues and metal, punk, progressive rock, Celtic and Latin rhythms, even hip-hop and reggae, but absolutely no pop or Top 40 hits. Most will know him from the Radiomarathon, the annual special-needs charity drive which he had a large part in creating in 1990, and presented for many years before withdrawing (he clashed, on-air, with a government minister). He turns 65 in March and is already on retirement leave, a soft-spoken man with olive-green beanie and thin, greying goatee.

A potted bio: his dad was Italian (hence the surname), but abandoned the family when Robert – the youngest of four – was still a baby. He worked menial jobs from an early age, packing okra in a vegetable factory and the like, but became besotted with music at 11 years old when his brother – an exchange student in the US – came back looking like a hippy, clutching Steppenwolf and Creedence Clearwater Revival records. “All my English,” he admits, “I learned from music.”

At 14 he started hanging out with an actual DJ, a guy spinning records in a disco, and was allowed to fill in while the DJ slow-danced with his girlfriend. The disco hired him full-time, and he also made playlists on cassette for satisfied customers. He was raking in around £200 a month, a princely sum for a teenager.

The money paid for six years in the US, studying Recording Engineering and Record Production. He came back – but Cyprus in the 80s offered nothing for a man of his talents. He returned to discos, but was bored playing “the same shitty music every night”. Finally, in 1989, Radio Super launched, the first private station. He joined them, and never looked back – though he might perhaps have done more, with his passion for music.

“I used to think that I was an anomaly on radio,” he muses. “But now I think I’m…” He pauses, giving it a wry spin: “Maybe I was geographically cursed”.

It’s meant as a joke – but he still looks surprised at the gales of laughter that erupt around the table.

“You and us both!” says Hakan. “We all are!”

It’s true, of course. Being in the Republic, pre-internet, with an obsessive interest in rock and metal music was a lonely business – but being a Turkish Cypriot youth with similar interests living in the north, before the checkpoints opened, long before YouTube and Spotify, must’ve felt like the loneliest place in the world.

“Back to the 90s, beginning of 90s,” says Kemal, a hearty type with a thunderous laugh. “I was a teenager. No internet. In the northern part of Cyprus, did we have any cassette shops? Very rarely.” Hakan recalls how his brother was friendly with a music shop in Turkey where “they used to actually record – illegally, of course – and copy the albums… And then this guy would send it through the post, and this is how we used to listen.”

Easy to forget the isolation, even – or especially – from the rest of the island. Easy to forget how the other side was shrouded in mystery.

Those who were around in the 90s may recall the year when forest fires broke out on the Pentadaktylos and the occupied side suddenly became a real place, as opposed to an abstract nothingness which we saw every day without seeing. Kemal has a similar memory from the other direction, in the back seat of a car going from Nicosia to Morphou (he was born in the village of Kazivera), seeing the lights on Troodos and wondering “why is it light? Why?… As a kid, I asked this question to myself”.

Robert’s shows, especially the ones in English – Friday night for rock and heavy metal, Wednesday for mellower tunes – served a similar function to the lights on Troodos, with the added plus of playing the kind of music you literally couldn’t hear anywhere else. “I wouldn’t miss your programme,” says Kemal. “I learned a lot from you. For example Uriah Heep, ‘Magician’s Birthday’. My Dying Bride, ‘Sear Me’ and ‘Turn Loose the Swans’. Lots of things… I also copied some of the programmes, I’m sorry!” he adds, laughing uproariously.

“And you’d also mention when there is a concert somewhere – Paralimni or wherever. ‘Wow!!!’,” he adds, doing a comically exaggerated version of his teenage reaction.

“We were like, ‘Maybe one day we will be able to go there’,” laughs Hakan.

Kemal leans closer to Camassa (the two of them huddle together for a while before we leave, sharing music-nerd factoids about years of release and who played bass on which heavy-metal track), and points to the sticker of The Wall among the small pile of gifts. “You know why I chose this?”

“Because it’s my favourite album!”

“Is it?”

“Of course it is.”

“Oh really? Very lucky that I chose it, then… But one reason that I chose it, is that you were actually kind of ‘breaking the wall’. The divide.”

Chaadash hasn’t contributed much, at least so far; he’s a decade younger, but grew up in a whole other era. He was just 14 when the checkpoints opened, 16 when YouTube was founded. “It’s five or six years ago that I actually found out about him,” he explains, pointing to Robert.

“I was listening to some good old rock music on the radio, I was like ‘Who is doing this?’.” Later he mentioned it to Hakan, “I was like ‘Do you know about this guy?’ – and he started to laugh. He was like ‘Are you kidding me? We grew up with this guy!’.” The weird thing, he adds, is that even he – a music lover in his 30s, living in the digital age – had to Shazam much of the music, as he’d never heard of it. “It was beautiful,” he says, bowing his head in appreciation. “Thank you very much.”

This is where it gets a little complicated – because Robert Camassa was always (for want of a better word) alternative; he’d have been alternative in Athens or London, let alone Nicosia. The notion of music as a unifying force, bridging the divide, isn’t wrong per se – but he wasn’t bridging it with Take That, or even Guns N’Roses (though he played Appetite for Destruction before it took off), he was doing it with the more rarefied likes of Ani DiFranco and Shub-Niggurath.

He was also (and remains) quite a low-key, world-weary character. I have to laugh when Kemal comes up to me – arms outstretched – crying “Mr. Camassa!”, clearly unsure what his idol even looks like. “I was 100 per cent sure that you were a smoker,” quips Chaadash to Robert, when I ask how they pictured him.

Oddly – and a bit paradoxically – I suspect it only added to his power. The mystery, the invisibility, the sense of a disembodied voice from across the divide which might as well have been coming from Mars, a connoisseur – an ‘anomaly’ – playing music for the love of music. Did the young Turkish Cypriots somehow sense that he was an outsider, like them? Or perhaps the music had its own power.

Robert wasn’t really Greek Cypriot, which might’ve alienated his listeners – at least not pointedly, or at least it made no difference. “It was based on music, and nothing else,” says Hakan, thinking back. “It was all about rock, it was all about heavy metal. We didn’t hear about all this katehomena [occupied areas], whatever… It was all about music. It was a kind of – what d’you call it? – a neutral ground”.

Ironically, the music seems to be what Robert Camassa is now losing faith in. Not the music he loves, of course, not the music of the past. He’s amassed thousands of albums on CD and vinyl, plus assorted merch, signed records and other memorabilia – he lives in a four-bedroom apartment, alone with his cat, “and I have no room,” he jokes dryly – and he’ll never stop listening to Dylan, Roger Waters or the rest of “the great artists”. The future, however, is another matter.

“Music is dead,” he says flatly. “For me, it’s dead… Nothing new is happening. And the new things that are coming up, they’re rehashing old stuff – and they’re very few. Most people are into AI now. I mean, why learn to play an instrument if you can punch six or seven keywords into a programme and get a song?”

Not at all, say the others. “AI is a dead end,” insists Chaadash (who’s the head of the New Media department, so he should know). AI just regurgitates, says Hakan; rock music has to sound new.

It’s a nice moment, a nice reversal – the grumpy old master set straight by his former disciples. But of course they have a point: Robert Camassa didn’t just play music on the radio, he inspired them – whether with his knowledge, his coolness, his suggestion of a world beyond the Green Line, even just his low-key presence – and young people need to be inspired. A machine can be impressive, but how can it inspire? It has no life.

Memories remain. The first time he heard ‘The Unforgiven’ on Camassa’s show – “I was in second grade of high school, it must be autumn 1991” – says Kemal. The way the guitar solo kicks in at 1:46 in ‘Skin o’ My Teeth’ by Megadeth (“One minute 46. I still remember”), says Hakan. “I guess you’re one of the last representatives of the educational music-show hosts,” says Chaadash lightly, and Robert chuckles.

“I’m the last of the Mohicans, man!” he quips – then shrugs noncommittally, the shrug of a man already thinking of retirement.

“I realise [all that] I’ve achieved, through my career in radio – but, to tell you the truth, I don’t have one single vain bone in my body… What I say is I did my job, or my hobby, the best that I could.” He may not have known about it – at least not until tonight’s meeting – but he did a lot more than that.