In August 2023, in issue number 97, the magazine Enimerosi of the Hellenic-American Educational Foundation listed the alumni of Athens College who participated in the newly formed government at that time.

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, 6 ministers (Dendias, Kerameos, Varvitsiotis, Kefalogiannis, Voridis, Papastavrou), 3 deputy ministers (Michailidou, Dimas, Kontogeorgis), and 4 more MPs of the New Democracy party (Loverdos, Panagiotopoulos, Pnevmatikos, Samaras) all had one common educational starting point, an alma mater, not a university, but up to the level of Secondary Education: they had all been students at Athens College at different times, over a span of 35 years, an element that serves as a characteristic and eloquent proof of how prominent Athens College’s presence is among the public figures and affairs of modern Greece.

In fact, the oldest diploma among those mentioned above, in this case, from Antonis Samaras, is dated 1970. While the most recent, that of Domna Michailidou, was awarded to the former minister as recently as 2005.

As for PASOK and its representation in the current composition of the Greek Parliament, both Pavlos Geroulanos and George Papandreou had attended Athens College – though they did not complete their secondary education there.

The latter is among the alumni who reached the highest executive office, the premiership.

The current Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, is a graduate of Athens College, class of ’86. His predecessors from Athens College include Antonis Samaras (class of ’70) and Loukas Papademos (class of ’66) – even though the latter had led a transitional, non-elected government during 2011-2012.

Even earlier alumni of Athens College who governed Greece included George Papandreou (2009-2011), who would have graduated in 1971 if his attendance had not been interrupted shortly after the military coup of 1967.

Athens College was also attended by his father, Andreas Papandreou, as a member of the class of 1938, although he too had to change schools before completing his education.

Thus, a part of Greek history, of politics and more, the national destiny of the country, one might say, is fed and closely linked to Athens College.

With one of the oldest and, objectively, the most renowned and iconic private schools in Greece, as 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of its establishment.

Dozens of Personalities

The history of Greece, from the Interwar period to the present day, as well as the unique history of Athens College, is composed of hundreds of smaller personal stories.

The lives and actions of people who excelled – or at the very least, distinguished themselves, influenced Greek society, and left a historical imprint in various fields of public life – from politics and business to science and the arts.

Alumni of Athens College include, for example, Spyros Latsis, a global banking and business magnate, as well as Dimitris Papaiouannou, one of the most creative and groundbreaking artistic minds Greece has ever known.

The MIT professor and visionary of the digital universe Michalis Dertouzos, Pavlos Alivizatos, a professor of Nanotechnology at the University of California, Berkeley, the renowned and prolific historian Thanos Veremis, and the left-wing intellectual, former minister under SYRIZA, Professor Aristeidis Baltas.

The shipowners Giorgos Prokopiou and Giorgos Oikonomou, as well as actors Kostas Arzoglou and Konstantinos Markoulakis.

The head of the Motor Oil Group and multi-champion rally driver Giannis Vardinogiannis, along with several other members of his family. Journalist Alexis Papachelas and Savas Theodoridis from Olympiakos.

The man of extreme adventure feats Nikos Todoulos and conductor Nikos Michalakis. Giorgos Kaminis.

Katerina Gkagaki among many, many others. In any case, the game of name-dropping is by definition lost in the shadow of Athens College, as it is certain that any attempt to fully list the VIP alumni, occasional students, etc., will always leave most people out.

Nevertheless, even for Athens College itself, which consistently and proudly promotes its illustrious alumni as an undeniable advantage over the competition with the other private schools of the informal “Greek Ivy League,” some students will always cause discomfort.

Miltiadis Evert, for example, was one of the difficult cases, uncomfortable for the narrative of the College’s excellence. He came from a powerful and famous family, but the late Evert himself was notoriously a poor student – especially in theoretical/literary subjects.

However, many years later, when he returned in glory to the College for a lecture as a minister and future leader of New Democracy, he had every right to share with the gathered students of his old school the thought that “being a good student is not necessarily a one-way street to success in life.

I, for instance, always got 20 in Mathematics, but not good grades in the others. Ancient Greek, Modern Greek, etc. were never to my liking. In the exams for the Evelpides, the academy I wanted to get into, I failed the essay. Despite that, as you can see, in the end, I did quite well.”

Similarly, Andreas Papandreou, whose blood was already boiling from his adolescence, managed to be expelled from Athens College in 1936.

The reason for the expulsion was the fiery Marxist articles he signed in “Xekinima,” a makeshift political criticism publication that Andreas published together with some equally fiery and restless classmates. And as a family tradition, George Papandreou also had to interrupt his education at Athens College – abruptly and violently.

Having witnessed the arrest of Andreas at the hands of the 21st April 1967 coup plotters, George A. Papandreou, who had been quiet and introverted until then, at just 15 years old, began to flirt with the distinctly forbidden under the circumstances created by the imposition of the dictatorship: resistance.

So when this reserved student, grandson of former Prime Minister Georgios and son of the “dangerous for the regime” Andreas Papandreou, attempted to write the anti-dictatorial slogan “Democracy will win” in paint on the outer wall of Arsakeio, not far from Athens College, he was arrested too.

It is said that he was beaten by the police before being handed over to his home. In any case, his mother, Margarita Papandreou, hurried to smuggle him to the USA.

War from the “Change”

The relationship of the Papandreou family with Athens College includes other episodes, certainly beyond the attendance of other members of the dynasty, such as the writer and current European Parliament member for PASOK, Nikos Papandreou, the children of George A. Papandreou, and others.

From a completely different perspective, in the first phase of PASOK’s governance of the country, during the years 1983-1984, the powerful and established Athens College came very close to bankruptcy and disappearance.

The school went through its most serious financial crisis in its history, which at first glance was due to the accumulation of deficits and debts, but at its core, the difficulty was the result of a suffocating restrictive – openly hostile – policy against the College from the government of Andreas Papandreou.

A private school with this profile was a thorn in the side of the enraged socialists and the anti-American hysteria orchestrated by PASOK during that period.

The College administration was deprived of the right to increase tuition fees in line with inflation, so the remaining means to prevent the school from suffocating due to lack of funds were cuts and fundraising.

Hence, an urgent attempt to attract donations was organized, a campaign under the dramatic slogan “Save Our School – SOS.” The response was immediate and substantial, as the parents of the students, along with alumni, and many wealthy Greeks outside the school community, created the coveted lifeline for Athens College.

A characteristic of the determination shown by some to keep the school alive at all costs is the gesture of Captain Yiannis Latsis, who covered exclusively from his own funds the debts of Athens College to the National Bank of Greece.

In connection with PASOK’s war against Athens College, there was a rumor that circulated, suggesting that beyond the financial pressure, some government officials had embarked on a plan to devalue the school.

According to the scenario, which was never substantiated or denied, the written exams of its students in the nationwide entrance exams were deliberately sent to working-class areas, such as Korydallos, with instructions to the examiners to apply maximum strictness in their grading.

This was supposedly the explanation for the sudden drop in the school’s success rates in the early 1980s, while previously, and after the PASOK government, Athens College candidates were entering universities with overwhelmingly high percentages, usually above 95%.

Sheep, both white and black

The entrenched stereotype that Athens College is inherently and unyieldingly a conservative school, with a corresponding political orientation, and that it does nothing but nurture the next generations of bourgeois citizens and politicians, was challenged with its ideological choices by Chrysanthos Lazaridis.

The later close collaborator of Antonis Samaras, his speechwriter, and MP for New Democracy in the 2012 elections, in the early 1970s, when the dictatorship seemed omnipotent, capable of detecting and suppressing any trace of resistance from its inception, was a leading figure in a very small group of alumni who self-identified as leftists—and ready for dynamic actions aimed at overthrowing the junta of colonels.

So, regardless of his later choices, young Lazaridis followed the solitary path of the rebel leftist, playing with fire in every sense, as the only former college student involved in the leadership of the Polytechnic Uprising in 1973 as a member of the Coordinating Committee of the Greek Students’ Union (EFEE).

But the occasional “black sheep” of Athens College were not only those students who strayed from the dominant political conservatism—regardless of whether Athens College itself consistently and officially ensures it remains free from any suspicion of ideological guidance of its students in any direction.

The College asserts itself to be completely and steadfastly apolitical.

However, at the level of adolescent subculture, many of its students have made concerted efforts to debunk the myth that they are “soft,” “boring rich kids” compared to students from other private or even public schools.

Hence, someone had the idea, around 1986-1987, to bring a herd of sheep into the Athens College campus in Psychiko for grazing—even though the hidden symbolism of this installation was never decoded.

In the unwritten mythology of the school, the “raids” of the 1980s have become legendary, where groups of Athens College students from the Psychiko campus would head to their eternal target, the Moraitis School. In at least one case, the animosity between the two school communities had escalated beyond all limits.

The warriors of Athens College went so far as to order “ammunition”—dozens of cartons of eggs, sacks of flour, and so on—which were transported to the battlefield by the responsible merchants in small trucks.

The consequence of the invasion and the ensuing conflict was the imposition of a severe punishment on the entire senior class of 1990: the traditional five-day school trip, which they had been eagerly awaiting for years, was canceled.

In the same spirit of college rebelliousness, when only male students were enrolled at Athens College, daily commando-style raids took place into the adjacent Arsakeio, which was, of course, its alter ego, as an all-girls school.

Even within the Athens College campus in Psychiko, the rush to adopt adult habits led to the establishment of the infamous “Tzoura Club,” a secluded spot within the grove near the central Benaki building, where unruly youths secretly smoked away from the watchful eyes of the supervising teachers.

Beyond the campus, there was always the café “Due Torri,” next to the Havana cinema on the side street of Kifissias Avenue, directly across from the main gate of the College.

Experiments with bravado, cigarettes, and beers went hand-in-hand—not always harmoniously—with first loves, under the conditions of approaching fellow male and female students in an era without mobile phones, without social media chats, and even before the pedestrian bridge was built over Kifissias Avenue in 2011, funded by the parents and guardians of Athens College students, after the tragic death of a child at the spot.

The study and construction of the bridge was undertaken for free by the office of architect and former chairman of the Athens College Board of Directors, Alexandros Samaras.

The Century of the College

The celebration of the centenary of Athens College includes a rich program of anniversary events, exhibitions, etc., which will unfold in the coming months.

However, back in October 1925, the school began with very few students, just 30 in total, slightly more than the number of students in an average class at Athens College today.

Now, in 2025, a “century of the College” after its establishment, the numbers seem to be galaxies away from the school’s humble beginnings: In the 2023-2024 school year, 2,023 students attended (861 in Elementary, 630 in Middle School, and 532 in High School), while the educational staff exceeds 250 educators of various specialties.

The school facilities include the historic complex of buildings along with newer additions and extensions in Psychiko, much more modern facilities in Kantza, as well as the kindergarten.

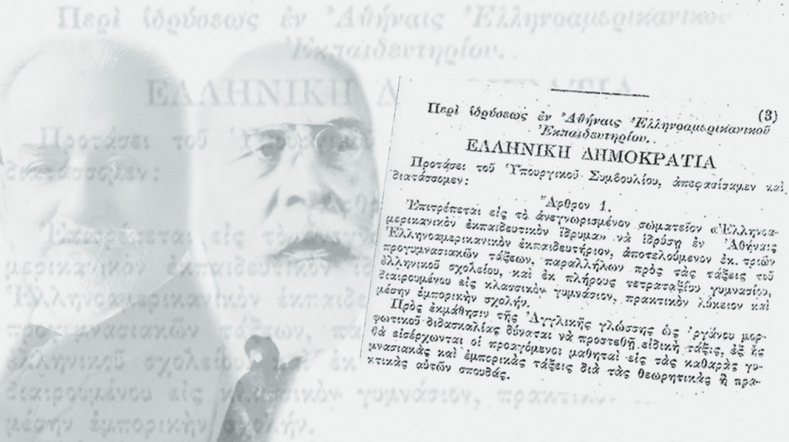

The present giant organization, in 1925, was the newly founded Athens College, carrying the clarifying subtitle “Greek-American School.” A newly established and romantic educational initiative, consistently oriented towards liberalism and the bourgeois conception of humanistic education.

However, the significance of the effort could not be undermined or ignored by the society of the time, given that the founders and benefactors of the project were individuals of immense stature, both economically and intellectually: Emmanouil Benakis, one of the greatest national benefactors in the history of the Greek nation, and Stefanos Deltas, husband of Benakis’ daughter, the writer Penelope (and grandmother of Antonis and Alexandros Samaras).

Deltas was a distinguished banker and intellectual, also involved in numerous charitable actions. Alongside them, Benakis and Deltas had a group of American Philhellenes who were eager to create a pocket of dissemination for a complete Greek-American education, a model school, in other words, a regular college in Athens.

In the words of Stefanos Deltas, the founders of Athens College “dreamed of a school that would produce men for our society with patriotism but also with humanism, honest characters, physically and mentally trained to fight life’s battle, as it presents itself today, with the basic knowledge provided by secondary education, and above all with the will to learn more and with the method to study and acquire other knowledge from life and from study.”

Classism and Display

Anyone who has attended an Athens College graduation ceremony at the end of each school year cannot help but feel awe. The procession of students lasts for hours; it seems endless.

So does the distinction of graduates in various fields of knowledge, whether in the conventional school program or in areas such as rhetoric, the arts, sports, etc. For nearly a century, with the exception of some periods during extraordinary events, such as the 1940-45 period when the school was transformed into a military hospital, occupied by the Germans, etc., the administration proudly announces the successes of the best: their acceptance into prestigious universities and higher education institutions in Greece and abroad, the rank each candidate achieved based on their high grades in the entrance exams, and so on.

At these events, the young graduates eagerly try on their new selves with heavy makeup, wearing formal attire, chic dresses, stilettos, suits, ties, etc.

Thousands of invited guests attend, many of whom arrive at the traditional headquarters in Psychiko with large personal security details.

This is because they either were students of the College themselves and now hold prominent positions in politics, business, etc., or they come to the grand and festive reception to witness a unique milestone in their children’s lives—their graduation from high school.

Indeed, these two roles often coincide, as the Athens College community has a powerful internal multiplication mechanism, ensuring—through preferential registration, discounts on tuition fees, etc.—that it keeps its former students, and their descendants, under its patronage for life.

In this way, as the Athens College prepares to celebrate its 100th anniversary with the appropriate grandeur this year, it manages to grow while simultaneously strengthening the sense that, in some way, no one ever truly leaves this school.

Complete severance and alienation from the College simply cannot be imagined—at least not for the majority of its students. Those who have passed through its classrooms belong to a large micro-community with its own codes of recognition, communication, and solidarity among its members.

A brotherhood, in every sense, with its positive and corresponding negative aspects. And it is this characteristic, the “belonging” to the Athens College clan, that makes it truly unique, as well as the fact that, objectively, it opens a door to a rather different world for its students.

The Inevitable Elite

After all, Athens College has always been its reputation. Private and economically inaccessible for the majority of Greeks, it remains a school of the elite and almost exclusively for an elite that can not only afford the tuition (12,000-13,000 euros on average per child per year) but also manage to pass all the “filters,” as not everyone who applies for admission is accepted. Of course, there is a scholarship system—which is the oldest in Greece—that opens the school’s doors every year to many underprivileged students based on academic and social criteria.

Nevertheless, Athens College, as an institution of education, culture, the production of social symbols, and even the maintenance or perpetuation of class stereotypes, is much more, much more complex, and multi-dimensional than it is often accused of being. The obvious and widespread ideology considers it a “window-dressing school” for the aristocracy, however that is defined by today’s terms.

Like a closed, snobbish club, a jewelry store for students who do nothing but incubate their superiority, spending at least 12 years and their entire childhood and adolescence within a mechanism that reproduces the domestic ruling class.

However, this approach to what Athens College truly is and represents is overly simplistic. It possesses some prominent characteristics—such as its constant and consistent focus on the pursuit of excellence, as well as a measured elitism—which shape its mark and identity. At the same time, however, it inevitably navigates its own contradictions, its own internal antinomies, just as happens in every living human community.

A graduate of 2002, director Grigoris Rentis, may have come closest to the most comprehensive and accurate description of what it means to belong to the small and, at the same time, vast world—almost devilishly small and vast—of Athens College: “Athens College is a space that you come to appreciate over time because, ultimately, in a sly and strange way, it manages, beyond education, to instill culture in you.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions