The showcases of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York are slowly being emptied of illegally acquired treasures that are now being gradually returned to Greece, following a successful long-standing collaboration between the New York District Attorney’s Office and the Greek Ministry of Culture.

After the 29 treasures that were repatriated three years ago—and others such as the legendary Griffin returned a few months ago—the return of 29 masterpieces of priceless value has now been announced. These date from the Neolithic period (5000–4000 BC) to the Late Hellenistic period (2nd–1st century BC).

These rare and expressive examples of sculpture, metalwork, and pottery are coming home to remind us of the great works from different moments of mainland and maritime Greek civilization, and of their brilliant history.

They were handed over to Greek authorities by Matthew Bogdanos, head of the Antiquities Trafficking Unit and Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan (a man who has worked tirelessly for the cause of repatriation), in a special ceremony held at the Greek Consulate General in New York.

Among the items that stand out are:

- Two stone axe heads from the distant Neolithic period,

- A Minoan agate sealstone depicting an ibex from the Bronze Age,

- Three marble bowls from the Early Cycladic period,

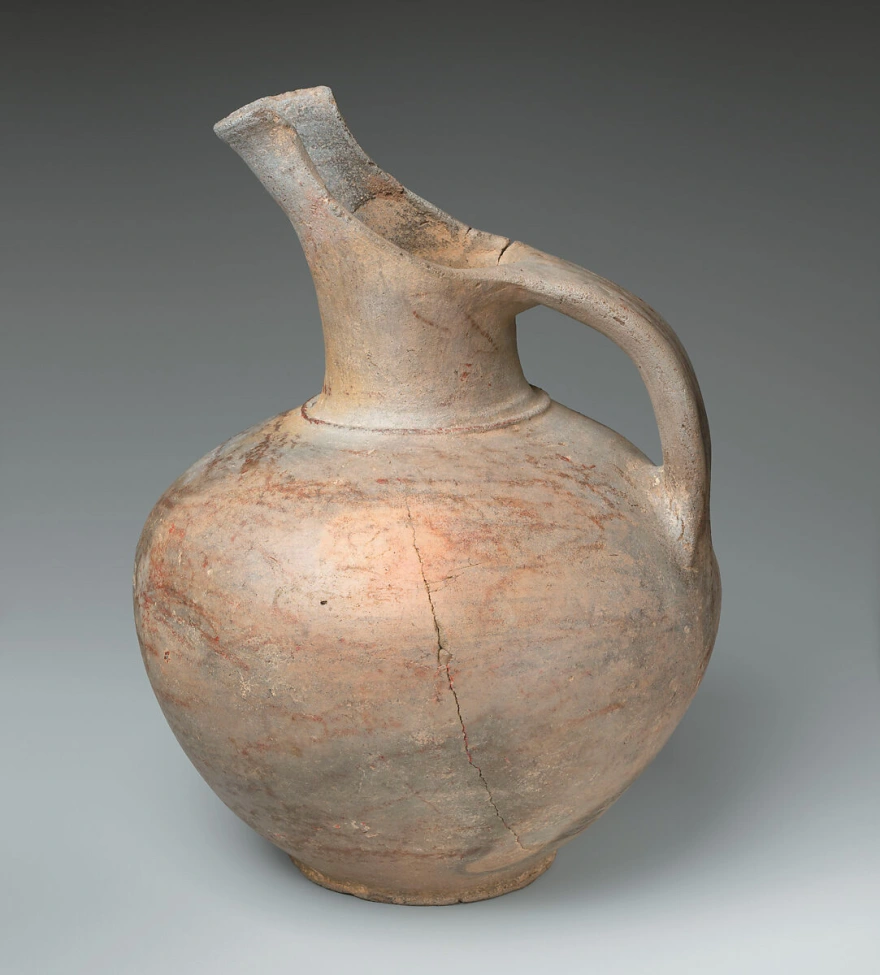

- A jug (prochous) from the same era,

- A Mycenaean false-neck amphora,

- Two bronze belt fittings from Western Macedonia,

- A marble head of a kouros from the Archaic period,

- A bronze ornament depicting the Gorgon Medusa, a finely crafted piece made in a Corinthian workshop around the same time.

A 3,000-Year-Old Jewel

The Minoan sealstone found among the treasures is a prime example of the high artistry of the Minoans and their remarkable craftsmanship—they engraved scenes of nature and daily life on small, hard, precious or semi-precious stones. Some sealstones, such as one found in a Mycenaean excavation believed to be of Minoan origin, even depict battle scenes from the Iliad.

These beautiful miniature works of art—praised in lengthy New York Times articles for their cultural importance—reveal much about the sophisticated artistic production of Minoan Crete. They stand out for their plasticity, three-dimensional form, fine detail, and pursuit of perfection.

It is astonishing to think that the elegant ibex carved on this tiny jewel was created 3,000 years ago in one of the artistic workshops of Minoan Crete, the only place capable of producing works of such aesthetic refinement.

Indeed, many of the motifs found on rings—ibexes, lions, griffins, fish, and scenes of daily life or athletic contests such as bull-leaping (Taurokathapsia)—also appear in the palace of Knossos.

Some sealstones even bear inscriptions in Linear B, which Sir Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who uncovered Minoan civilization, attempted to decipher.

Many of these sealstones have been dispersed across the world, such as those in the Ashmolean Museum, which houses Evans’s archive and numerous treasures he collected from Cretan villages where locals had kept them safe. These sealstones were so deeply woven into the island’s history that the Cretans themselves adopted them as protective amulets, just as the Minoans had.

The Theft of the Amphorae

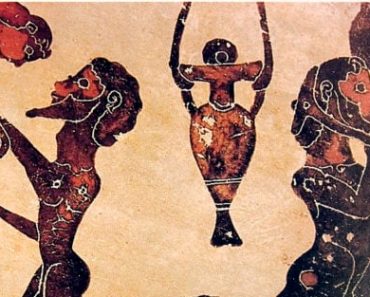

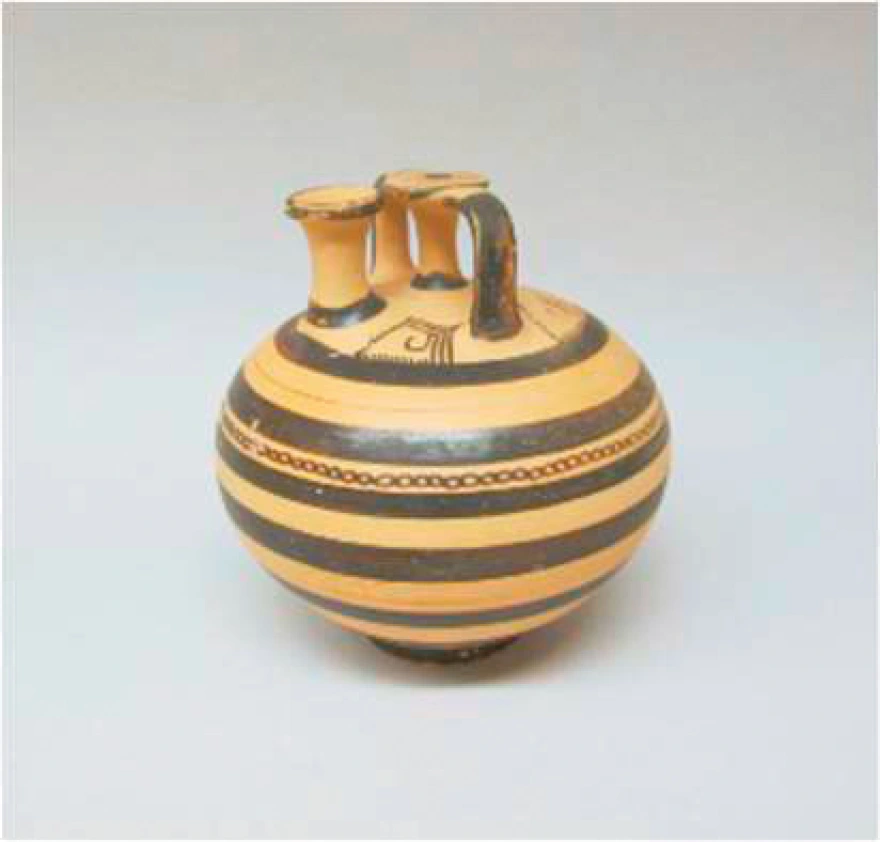

Beyond jewels such as the sealstone and the gold necklace, among the 29 ancient treasures returning to Greece, the magnificent amphorae also stand out. The Mycenaeans, inheriting the Minoans’ artistic skill, were master potters, decorating their vessels not only with geometric motifs but also with sea creatures, such as octopuses.

Many Mycenaean vases have been found throughout the Mediterranean, particularly in Cyprus, reflecting the close ties between the Mycenaeans and the Eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age.

The Mycenaeans appear to have taken full advantage of Cyprus’s strategic position and copper resources. A characteristic example of Mycenaean craftsmanship is the false-neck amphora that once stood in the showcases of the Metropolitan Museum. Today, if one looks up this artifact—or others from the museum’s major donor collections—it appears marked as “Unavailable”, precisely because it has been seized by the New York DA’s Office for return to its rightful home: Greece, but also Italy, Turkey, and Cyprus.

The label “Unavailable” accompanies the description “Mycenaean false-neck amphora,” though, of course, it does not mention that the object had been stolen, like many other treasures looted by Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the U.S. consul in Cyprus in the late 19th century.

Di Cesnola was a notorious antiquities looter who conducted illegal excavations, many of whose finds now adorn the displays of leading museums—from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg to the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

In a special article, the New York Times noted that his obsession was so great that he amassed over 35,000 antiquities, virtually emptying the Island of Aphrodite (Cyprus) in order to establish his own museum.

When that failed, he ensured his appointment as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a position he held until his death in the early 20th century.

More than a century later, the famed “Palma di Cesnola Collection” has been proven to consist almost entirely of illegally excavated artifacts, just like several other major collections—such as the Stern Collection, many treasures of which were also recently recovered by Matthew Bogdanos.

The investigation led by Bogdanos and his team, in close collaboration with Homeland Security Investigations and the Greek Ministry of Culture’s Directorate for Documentation and Protection of Cultural Goods, extended beyond the Metropolitan Museum to objects about to be auctioned.

After proving the illegal origin and trafficking of these antiquities, the authorities seized them and returned them to Greece, permanently changing the way the world’s top museums operate.

Lina Mendoni: “The struggle requires a lot of work”

“Every repatriation of Greek antiquities is an extremely significant event and validates the policy of the Ministry of Culture in recent years,” stated Culture Minister Lina Mendoni regarding the positive news of the repatriation of antiquities, emphasizing that “Greece is now internationally recognized as the country that has placed very high priority on policies combating the illegal trafficking of cultural goods, a phenomenon directly linked to organized crime and terrorism.”

This was also evident at Mondiacult, the global conference on cultural policies organized by UNESCO in Barcelona.

The recent success of the Antiquities Trafficking Unit, led by Matthew Bogdanos, and the Department of Homeland Security Investigations fills us with joy and optimism.

I have said many times, and will continue to emphasize, that the fight against the illegal trafficking of cultural goods requires strong collaborations and a lot of work.

It is fortunate that we have managed to build and maintain these collaborations and see tangible results. Warm thanks to all those who contributed to the return of these 29 antiquities.

Both the Greek Minister of Culture and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the context of their good cooperation—since the museum consents to the return of the stolen items—have committed to doing whatever they can to promote shared values and Greek culture, not only collaborating on the issue of antiquities but also working in the same direction in cultural diplomacy through the exchange of treasures and joint events.

Within this framework of collaboration, an exhibition will be organized next year at the Met titled “Across Wine – Dark Seas: Art and Identity beyond Ancient Greece.”

The exhibition will open with a series of Greek exhibits, which this time will adorn the museum’s cases as loans, exemplifying how the British Museum should operate by returning the Parthenon Marbles—demonstrating high cultural standards and equally constructive collaboration.

The courage of the “Greek Indiana Jones”

A leading figure in the fight for the repatriation of antiquities is undoubtedly the head of the special Antiquities Trafficking Unit, Deputy District Attorney at the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, Matthew Bogdanos—the “Greek Indiana Jones,” as he has been called.

Through meticulous investigation and by extending his networks across all major museums, Bogdanos has demonstrated that prominent private collections, seemingly beyond suspicion—such as that of Leonard Stern—have not only acquired treasures illegally but also sought to conceal their antiquities trafficking by making “generous” donations.

After the revelation of the story of the golden crown returned to Greece from the Getty Museum, a bright path opened for the repatriation of cultural goods.

Now, several years later, the Greek-American deputy district attorney raises serious questions about the acquisition of treasures by the Met, revealing the practices of top museums worldwide as well as auction houses that sell antiquities without concern for their provenance.

As the New York Times reported, Bogdanos was the first to boldly knock on the doors of wealthy collectors like Michael Steinhardt, who possessed countless treasures, and began examining all exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum, most of which were illegally acquired.

Clearly, courage has never left the Greek-American prosecutor, who had already received recognition from the U.S. government with the National Humanities Medal for recovering treasures after the looting of the National Museum of Iraq—his first major success.

This was followed by his battle to reclaim the famous Euphronios Krater, stolen from an Etruscan tomb, which he won—a surprising victory that changed the mindset of museums.

After his latest success, the repatriation of 29 antiquities to Greece, Matthew Bogdanos stated that “this success is due to my collaborators in both the Antiquities Trafficking Unit and the Greek Ministry of Culture, who always contribute seamlessly and willingly to the documentation of the objects.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions